The Fiddlehead Editor Sue Sinclair interviewed Ariel Gordon, this year's judge of our Creative Nonfiction Contest, about writing poetry, writing creative nonfiction, and integrating science in her essays.

Photo credit: Mike Deal

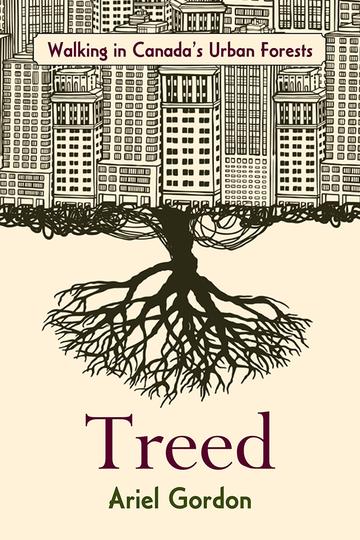

Sue Sinclair: You published poetry before you published Treed, and your forthcoming Tree Talk ricochets back into poetry, though urban forest straddles both genres. How do you feel poetry supports your work as a CNF writer, or does it? What does CNF offer you that poetry might not?

Ariel Gordon: Though prose doesn’t have the same compression as poetry, the same reliance on sound, I found that the writing of CNF essays and poetry felt very similar in all but one respect: volume.

When I was working on Treed, I’d written several long poems and had ordered two manuscripts and any number of chapbooks, but editing 5,000-word essays, which works out to about 17 or 19 pages, nearly killed me. My internal monologue during editing sessions probably sounded something like this: “I feel like I’ve been scrolling forever. Ugh, how can there be MORE of this essay. SO MUCH SCROLLING.”

I turned to prose for Treed because it felt like I needed a bigger container—a bigger canvas?—than poetry offered for the ideas I wanted to explore, especially when parsing complex scientific principles, which often required quoting experts. I love poetry and will never not-write poems, but my poetry is much more focused on moments in time, on the pleasures of language-play, on texture and tone.

That said, the essays I’m happiest with in Treed made poetry-like connections between seemingly unrelated subjects. My essay “Soiling myself,” for instance, was about foraging for mushrooms in the city, my leaky peri-menopausal body, undisclosed lead pollution, and suffragette Nellie McClung.

In the end, I think CNF offers me what poetry does: the chance to express myself, to experiment and play, and to be in dialogue with readers.

SS: CNF seems to be burgeoning just now—any thoughts on what’s up with that? Or do you have a different perception?

AG: I think there’s a burgeoning in Canadian literature—there’s so much great CNF, poetry, and fiction being written. It’s almost impossible to keep up with it all, but it’s rewarding to try!

My take-away from the last decade of reading and writing CNF is that it’s a very malleable form. It can be molded into memoir, history, personal essay, or literary journalism. It can be light or heavy. It can whisper or shout.

The thing I’m most looking forward to in judging the contest is being walked through the form as it’s currently being practiced. As if CNF was a neighbourhood.

SS: What will you be looking for in the CNF pieces entered in the contest?

AG: I’m trying to not go in with any expectations, except that I want to be convinced by the entries, to enter them completely.

SS: Can you say something about the challenges and delights (I presume there are both?) of integrating science into your essays, and could you perhaps share your writerly strategy or approach?

AG: My original plan was to become a science journalist as my mother was a radiation safety officer and throughout my childhood talked about the lack of understanding of basic scientific concepts. So I did a BSc and a Bachelor of Journalism while writing poetry on the side. After six months of working as a freelance journalist, I dipped into my notebook and saw that I hadn’t written much of anything for months. This was terrifying, given that I’d had a writing practice since I was thirteen, and it was the most important, most joyful part of my life. So I gave up journalism and started over in arts administration. Nearly twenty years later, after publishing two books of poetry focused at least in part on urban nature, I started writing the essays that would become Treed, which somehow drew on ALL of my experience and training.

There were challenges in that I was teaching myself how to write long-form prose while also trying to figure out how to combine science writing with the personal essay. Which is to say that I made everything much harder than it had to be, but I learned a few things.

First: I could research the hell out of a subject, but until I had a meaningful personal story to go with it, a narrative, I didn’t have an essay. Second: I had to then be careful not to let the story overwhelm the science. It was very important to me that I got the science right. Third: though I worked on Treed for five years, I really only figured out how to write essays-that-worked in the year before publication. Luckily, I’d been writing like stink the whole time, so when I figured out the how, I had a lot of what to work with.

To sum: CNF pieces have their own parameters and constraints, their own internal logic, which should be obeyed. (Unless it’s generative to break those rules….) And, as writers of CNF, you can expect to rewrite and rewrite your pieces until they are suddenly done.

Ariel Gordon is the Winnipeg-based author of the poetry collections with Palimpsest Press, Hump and Stowaways, both of which won the Lansdowne Prize for Poetry. Recent projects include the anthology GUSH: menstrual manifestos for our times (Frontenac House, 2018), co-edited with Tanis MacDonald and Rosanna Deerchild, and the fourth installment of the National Poetry Month in the Winnipeg Free Press project. Her latest book is Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests (Wolsak & Wynn, 2019), a collection that crosses science writing with the personal essay while walking under—and considering our relationship to—trees. Treed has been nominated for the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Awards at the Manitoba Book Awards (the winner will be announced on Friday May 15) and was given an honorable mention for the 2020 Alanna Bondar Memorial Book Prize for the Environmental Humanities and Creative Writing.

Add new comment