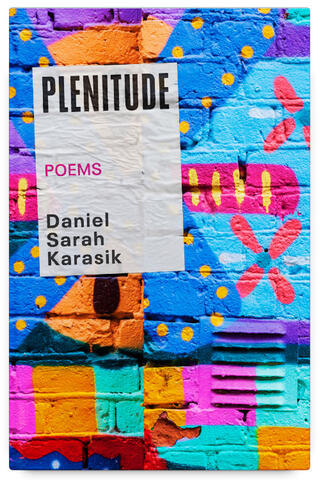

Daniel Sarah Karasik’s Plenitude is not only a cogent articulation of trans experience, identity and rights, but an incisive systemic reading — often a socialist or Marxist reading — with several side trips to consider Jewishness. By situating gender, queerness and identity within the larger context they bring a broader analysis of how culture can subsume and often commodify the personal. And because this is poetry, we’re aware that the tropes of lyric positionality (including the lyric “I”) are also implicated.

The three-part poem “stage of grief,” is a good illustration of this. The first section “in which / you believe / any and all / disclosure / of your pain / is a step / towards healing it,” establishes what we recognize as the normative “brave” position of the contemporary moment. Think of how social media encourages disclosure and how it is rewarded. Likewise, how disclosure of individual pain is one significant MO of contemporary poetry.

The poem’s second section zooms out to reveal the neo-liberal system “in which / you recognize / the political mechanisms / that encourage us to mis-take / disclosure for healing / while depriving us / of resources / for trans-forming / one into the other.” The individual exists as part of a larger structure and their individual choices are reliant on social and political structures. We as readers are brought into the discussion by the use of “you” and “us.” The personal is political. The reader is part of this society, too.

The third section, the coup de grâce, “in which / you perceive / the dominant system’s / foundational assumption / that healing is impossible / but aspirations to it / infinitely monetizable, / that system’s / clear material interest / in replicating harm / as it pretends / to facilitate / repair[.]” BOOM as they say. The personal is coopted by larger capitalist politics. This is the contemporary Gordian knot: we may experience the stages of individual grief à la Kübler-Ross, however there are also meta-stages where we come to understand how our grief is entangled with larger forces which complicate and often obscure the individual, how our individual grief is part of a system-wide economic imbalance and the abandonment of the individual and the disingenuous com-modification of the entire process.

If “stages of grief” articulates Karasik’s fundamental point-of-view, its technique also reveals one of the book’s strengths. Many of the poem have a “turn,” a volta, which in some way twists the reader’s assumptions. We discover that the “stages of grief” are not the personal ones but a burgeoning understanding of larger forces which affect the individual. Each section is a kind of plot twist.

Like “stages of grief,” “messianic time,” the epigraphic poem which begins the book, refocuses our assumptions by calling on us to imagine the eponymous “messianic time,” a utopian heaven-on-earth without oppression. This utopia doesn’t have violently politicized or essentialized identity, but rather “limitless forms of descriptive difference.” That’s a beautiful breaking down of limiting and controlling taxonomies of identity in all its forms. Then a deft turn to expand the idea: “if we were to say I in such a world, we might mean almost nothing but a historied, futured, networked locus of desire[.]”

This phrase, “a historied, futured, networked locus of desire” is marvellous. Listen to the energized play of vowels and those t’s, d’s, s’s and r’s. It also contains the elegantly oxymoronic “historied, futured” — this utopia exists in the possibilities of the past and the future, it understands the context of history. And, returning to the notion of identity, never mind reductive discussions of the washroom-talk to which reactionaries constrain identity, Karasik here expands the self (the “I” which “means almost nothing”) to an exquisite vision of a “networked locus of desire.”

In “Regarding the Prophetic Tradition,” they speak about Jewishness as they do in several poems and here specifically about “A Jewish predilection for the vatic voice,” and while “the poets have described the world; the point, however, is / . . . / to sing desire into a loving, / fighting sociality.” The personal (identity and desire) are political. Karasik often locates one aspect of their identity, their positionality, as a Jew (“I get Jews / confused, / am Jewish so allowed to” (“Spilling over.”) They are perceptive about the complex and often paradoxical positionality, the “caught-between” “whiteness” of Jews. For example, “I don’t know how / to reconcile my guilt at having / this much power / with rage at having so much less / than is imputed to me / by those who would like to see me dead,” or “sure. we could just hide, and wait / for whiteness to evict us. Like it’s always done.” (“Among Other White Jews.”) However, Karasik’s Jewishness is clear about Middle East politics: “poetry about silence wins prizes / as long as it’s silent about Palestine.”

These poems are infused with queer desire and political energy.

In some poems, ideas are expressed directly, however, the most powerful poems (most of the poems in the book!) while often deceptively straight-forward, engage Karasik’s talent for the telling turn, their adroit wit and incisive analysis and their undaunted, energetic and unembittered activism, such as in the poem “energy,” here quoted in full:

In Plenitude, Karasik, though they are unsparing in their examination of the dominant understanding of gender, politics, labour, capital and state power, ultimately their book is an intelligent, inspiring and moving celebration of the plentitude of desire and of possibility for both person and future.