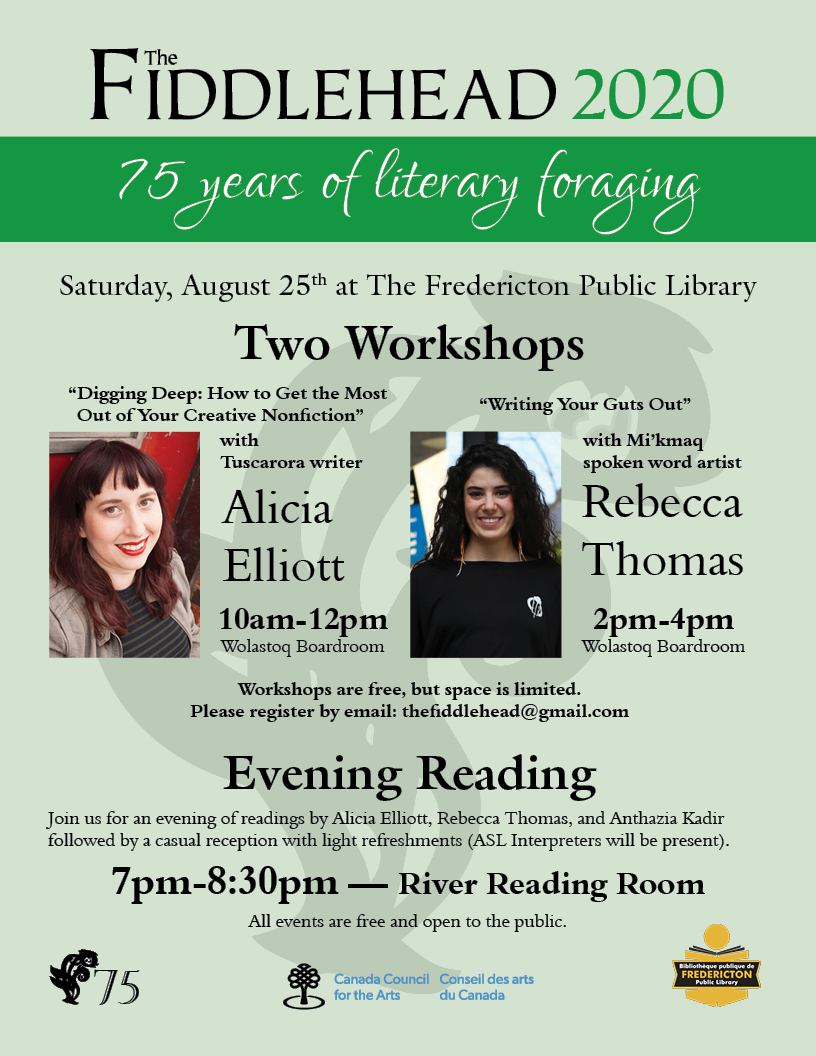

Interview by Emily Skov-Nielsen, Marketing and Promotions for The Fiddlehead. Alicia Elliott will be in Fredericton on August 25 to give a workshop "Digging Deep: How to Get the Most Out of Your Creative Nonfiction" from 10-12 at the Fredericton public LIbrary and to give a reading later that evening at 7pm, also at the Fredericton Public LIbrary. For more information, visit the Facebook event here or scroll down to see the poster.

Emily Skov-Nielsen: Firstly, I’d like to start off by asking a question regarding the upcoming workshop that you’ll be offering as part of The Fiddlehead’s 2020/75th anniversary events: “Digging Deep: How to Get the Most From your Creative Nonfiction.” I’m wondering what you plan to address in this workshop, and for anyone who might be interested in participating, what should they expect going into it?

Alicia Elliott: The most exciting thing about good creative nonfiction is also the most terrifying: baring your innermost thoughts, flaws, traumas. You need to be willing to really interrogate why you think what you think, do what you do. How you’ve been shaped by those around you. How you’ve shaped those around you. I think there’s this tendency for everyone to believe that they’re inherently good, inherently right, that they shouldn’t peer too closely behind the curtains in their own minds. That’s fine for some, but it does not make for good creative nonfiction. In fact, I’d argue that entire idea and the work it creates is fiction — and bad fiction at that. What I want to do in this workshop is encourage writers to go deeper into their own stories, to fight through the discomfort. I’m actually going to be pretty vulnerable here, and show some edits I’ve gotten for my upcoming book that have pointed out places where I’ve held back — and I know better. Hopefully this will help writers become better editors of their own work and create the best writing they can.

Emily Skov-Nielsen: In relation to your essay, “On Seeing and Being Seen: The Difference Between Writing With Empathy and Writing With Love,” I thought that differentiating between empathy and love was compelling and thought-provoking since the two are so often conflated. You touched on this in your essay but I’d like if it you could delve more into what you see as being the key differences; what does love offer in literature that empathy lacks?

Alicia Elliott: I’m currently resisting an urge to copy and paste a section from that essay right here. (It’s fresh in my mind since I just finished editing that essay for my book yesterday.)

I think that the problem with relying on empathy to guide your writing is that often we try to imagine ourselves into another person’s shoes, if you’ll forgive the cliché. But how can you really do that when you’ve never experienced what that person has? When you’ve never gone through what they have to lead them to that point? Essentially, empathy can rely on you writing over another person’s unique perspective and experiences by writing yourself into a situation or culture you may know nothing about. I’m sure you can see how that could lead to not only misrepresentation, but just plain bad writing.

When you use love to guide your writing, though, you (ideally) see a person’s joys, sorrows, strengths, weaknesses, flaws, suffering — you see it all, and you love it anyway. From a craft perspective, if you write with love, it means that you have a fuller picture of the people you’re writing about, you care about making sure that you have all your information correct, that you write it the right way. . . . Essentially, writing with love makes for better writing because it encourages you to be better and more responsible to your characters — and the people who see themselves in your characters.

A good example of this is Katherena Vermette’s The Break. I didn’t necessarily like every character in the book (and I don’t think you have to), but the complexity with which Vermette wrote them — the love with which she wrote them — made it so that I saw every character as a full, real person that I could know, even though they were totally fictional creations. The funny thing is, when you write with love, it actually does allow people to empathize in ways they might not otherwise. Look at how long The Break has been on the bestseller list! Look at how many awards it was nominated for! Look how many awards it won! Clearly it wasn’t just being read by Metis people living on Winnipeg’s north side. This is what so many people miss about writing with love: it creates richer work that can be accessible to everyone, because everyone responds to love.

Emily Skov-Nielsen: I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the commodification of Indigeneity and whether or not this a concern for you?

Alicia Elliott: At the moment, this question is still too vague for me to give a full, correct, responsible answer. Who is the one commodifying in this scenario? Is it companies taking Indigenous designs, getting child labourers in foreign countries to make cheap knockoffs, then selling these knockoffs to white people in North America? Is it people like the Acadian Metis, who are trying to interfere with the treaties of the Mi’kmaq? Is it pay-for-status white people creating their own tribes so they can be recognized by the Canadian government and “cash in” on our rights? Is it legitimate Indigenous beaders selling their goods on Etsy?

And why are these people commodifying Indigeneity in the first place? Is it for money? Is it to erode Indigenous rights and land claims? Is it so they can look edgy at Coachella? And what do we mean by “Indigeneity”? What exactly is being commodified? Indigenous identity, language, culture, land, treaty rights?

My answers to each variation of this question would depend entirely on what specific context you are referring to.

Emily Skov-Nielsen: In closing, since you are The Fiddlehead’s inaugural Creative Nonfiction Editor ― congratulations by the way! ― I’m wondering what you’ll be looking for when making your selections for publication; what moves you and what would you like to see more of in contemporary creative nonfiction?

Alicia Elliott: I already made the decisions for the first all-CNF issue and actually just finished the edits with the writers last week, so I’m pretty happy about that. There was an incredible range in the submissions, which is part of what I love about this genre. It encourages people to write their story however it needs to be written — whether that’s poetry, lists, fragments, linear essays, letters. . . . I’m incredibly excited for the issue to get into readers’ hands and see what these talented writers have done with CNF.

As for what moves me in CNF: passion, always. If you write something with passion, there’s something pushing the writing forward that you can’t quite put your finger on, but you can feel with every sentence, every word. I honestly think I’m seeing what I want to see in creative nonfiction: people willing to take risks and play with form, with content, with structure, with diction and/or syntax, to tell the story they want to tell, the way they want to tell it.

---

Alicia Elliott, a Tuscarora writer, has written for Globe and Mail, CBC, Hazlitt and others. Her essays have been nominated for and won National Magazine Awards, and her short fiction was selected for Best American Short Stories 2018, Best Canadian Stories 2018, and Journey Prize Stories. Tanya Talaga selected Alicia to receive the RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Award this year. Her first book, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground, will be published in March 2019 by Doubleday Canada.

Add new comment