Marco Melfi’s Reading Recommendation:

After I finished The Story of the Lost Child, the final book in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet, I was torn: do I immediately seek out her other books? What if they fall short of the enjoyment – and my high expectations – I felt after reading those four?

Eventually I read The Lying Life of Adults. It focuses on a teenage girl and the unraveling relationship with her parents, their secrets, and the relatives they keep from her. It has a similar energy to the quartet, probing the fraught realities and ironies of families and is richly animated by the city of Napoli. But the quartet – the characters, the conflicts, the outcomes – still left the greater impression. Until I read The Lost Daughter.

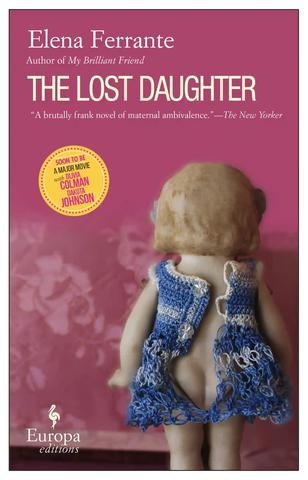

The Lost Daughter follows Leda, a middle-aged divorcée with two adult daughters who live in Canada, on a solo vacation to a coastal Italian town. Leda can’t ignore the happenings of an Neapolitan family she sees daily at the beach. In particular, she is captivated by Nina, a young mother, and her three year old daughter Elena. As Leda observes the mother and daughter, including how Elena plays with a doll, Leda reflects on her own relationship with her mother, daughters and other women from her past.

Ferrante’s ability to capture the interiority of a character is compelling. The book opens with a vague semi-confession by Leda: “At the origin was a gesture of mine that made no sense, and which, precisely because it was senseless, I immediately decided not to speak of to anyone. The hardest things to talk about are the ones we ourselves can’t understand.” Leda is honest, unremorseful but conflicted, as she examines her past and present actions and their motivations.

Leda strives to be a different woman and mother than her own. Yet Leda feels suffocated by her daughters, competitive with them; that they have subtracted something from her. She wants “to be seen by them as a person and not as a function”. While Leda’s daughters make “a constant effort to be the reverse” of her, Leda hopes she offers Nina a glimpse – in the same way Leda was stirred – towards an alternate future.

Ferrante constructs detailed scenes to vividly show interactions (e.g. Leda’s outburst in her kitchen after her young daughter hits her) or to convey mood (e.g. a pinecone that violently hits Leda; or a cicada Leda finds on her pillow). The recurrence of the doll, a dress and a pin grounds the story in relatable items which Ferrante leverages to reinforce themes of womanhood and motherhood; dependency and independence; escape and abandonment.

It may be unfair to compare an author’s works, especially when one is a powerful series that spans over 1600 pages and the other is a novella. But at the moment The Lost Daughter, with its arc, its candidness, and satisfying ending, is sticking out for me as my favourite Ferrante story. Now, the question is: do I wait or start The Days of Abandonment?

Marco Melfi is a graduate of Simon Fraser University’s The Writer’s Studio. His poems have appeared in The Antigonish Review, The New Quarterly, Prairie Fire, The Arc Award of Awesomeness, Funicular, and FreeFall. His chapbook, In between trains, was published in 2014 and his poem "The Faulty Porch Light" won The Fiddlehead's 2021 Ralph Gustafson Poetry Contest. He lives in Edmonton on Treaty 6 Territory.

Add new comment