What gift did I want for this birthday of mine on April 23rd? Shops were closed during a COVID-19 spring, but we don't ordinarily shop for presents. My husband is an excellent on-stage presenter and for my gift I asked him to read 'Riding Westward' to me. Its author's best poems are among the very best. And ever since religious doubt entered my heart, shortly after puberty following a devout childhood, I have wanted that skepticism to go away. Then again I haven't. I take religion and its icons as metaphoric language, and am devoted.

I believe that John Donne never ceased to grapple with faith. Although he became Dean of St Paul's, and his tomb in the crypt was spared the Great Fire of London, I sense that he hadn't an easy time spiritually. Among the causes were certainly his times. For he was caught, like William Shakespeare and my ancestor Bishop Edmund Strange Bonner (aka 'Bloody Bonner') in the reformation-counter-reformation flip-flop of religions bequeathed to England by Henry 8th's cunning conflation of church and state. But whatever the exigencies of public life, the complexity of Donne's soul, sense, and language would never have let him be on easy terms with a creator. His top poems are infused with physicality, embody the libido of language, the coition of argument and metaphor.

His late poem 'Good Friday, 1613. Riding Westward' opens 'Let mans Soule be a Spheare, and then, in this,/The intelligence that moves, devotion is" and delineates with a progression of polarities—rising and falling, living and dying, Zenith and Antipodes—his body moving toward a destination in the west as his soul looks east toward the crucifixion in Jerusalem of "that flesh which was worne/by God." Donne delights in being a both/and, rather than an either/or, human being. He includes God's mother as equal half in his Good Friday grieving, an out-of-step position in some quarters in his times, and ends with a string, nay, a pile up! of seductive comparisons, charging, nay, daring! the divine figure looking his way to, in a sense, seduce him by such grace that he in turn must turn and look, and meet that gaze. But what resistance!—evidenced by the prolongation of statement via image after image—as deeply wound inside the poet's being as the sound of his words are with their sense on the page. The poem culminates at under 50 lines and its series of lines halfway through (which I'll not spoil for you by quoting) are among the few ever composed that give me every time the time of my life.

Soon after my present was presented, a friend and his daughter visited for some homeschooling in the gardens, roaming about and observing and her writing a report—an original poem read to us! Before the roaming, he filmed my husband reading Donne's poem—for it's also one of his favorites. So we've a digital file. 'Riding Westward' though is so sensory that I find myself more moved by actually hearing it, in real time as they say, read from the book in my hands or another's.

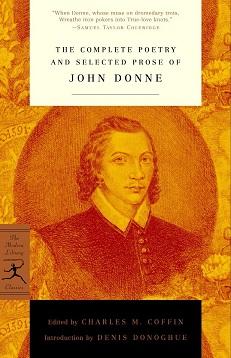

I suggest you dip into the Modern Library edition of The Complete Poetry & Selected Prose of John Donne. I've never read it as a page-turner, cover to cover. What I suggest is to browse a little here & there and then return for a long look at, a long listen to. one of the favorites you have found—perhaps by bibliomancy, perhaps by recommendation, perhaps by the attraction of its title or enticement of its genre. Start with the 17th Holy Sonnet, or the 14th, or with one of the Epigrams, or the Satyres, if that's your predilection. If you prefer prose, assay a small piece: the sermon on Candlemas Day with its eroticized and financialized image of the soul, or the first prayer from 'Essayes In Divinity' with its masterful periodic sentences. By my lights, though, it's Donne's poems that can leave me standing and breathing, whatever the day, whatever the news, in—trance, dance—both immanence and transcendence.

Add new comment