By Corinne Shriver Wasilewski

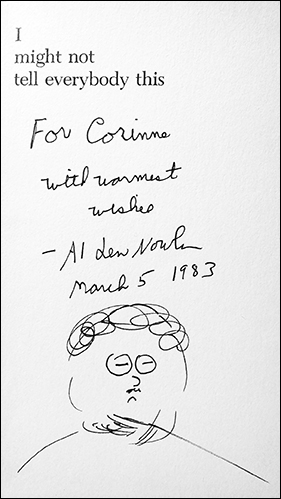

I met Alden Nowlan when I was just seventeen. A classmate and I wrote him a letter requesting his help with a project for school. He replied right away, inviting us to meet with him in Fredericton. I was thrilled — we’d get an amazing grade in English, plus, meet a real writer. It was March 5, 1983 and high school graduation was less than four months away. If I could make it through to June, I’d emerge a new woman; a woman who’d finally decided what to be and how to get there. Meanwhile, my university applications covered the gamut and were going out across the Maritimes.

June was also the month Alden Nowlan would die. I didn’t know that then, of course. I don’t think anyone did.

The day of the interview was bright and sunny, that’s what I remember; one of those days in late winter when the sidewalk is awash in slush and it’s too hot for mittens or to wear your coat zipped up. My classmate’s mother drove us down. It was an hour’s drive from Woodstock if you weren’t stuck behind pulp trucks. We took the old Trans-Canada, the one that’s rarely used now; the one that winds along the St. John River and uphill and down. The river would have been frozen and covered by snow, but, the view still magnificent and far superior to the view from the highway today that’s been carved through the rock and is closed in by trees.

I wore a cream coloured sweater with a pink blouse underneath. I know because of the picture. My face is pink to match my blouse, my smile wide. Alden Nowlan wore a button up shirt, light brown with a rust coloured tie. A pen pokes out his breast pocket. His arm circles my shoulders and holds me close. He looks a bit like the cat that swallowed the canary. Or perhaps he’s amused.

He welcomed us like old friends, and, in a way I guess we were. I’d read his poems and stories and knew we shared the same world. Hartland? I could bike there and back in an afternoon. The St. John River? It’d been the backdrop to my life from the time of my conception. Fredericton and Saint John? I could find my way to K-Mart, Zellers, Brunswick Square, and Kings Place with my eyes closed.

I lived among his characters. They were my family, friends and neighbours. I’d played key parts myself: the lonely child who builds kingdoms in her mind and the adolescent full of longing, while, the role of stressed out adult/killer of imagination waited for me in the wings. As for all the religious zealots that figure in his work, my family was three parts Baptist and one part Pentecostal — enough said.

My hope was in Alden Nowlan that day. Looking back on it now, it was unfair to both of us. He’d not read my report cards, the one from grade four that says “Corinne has shown a love for story writing this year” or the one from grade five that says “Corinne has very good original written work” or the letter from my grade six teacher that says how she appreciated my talent for writing creative stories. He knew nothing about my love for reading or how as a child I’d vowed to read every children’s novel in the L.P. Fisher library and made it all the way to ‘F’, but, just couldn’t get through “The Black Stallion” no matter how hard I tried. He didn’t know about my rigorous religious training and how I’d come to see all writers as prophets and books as somehow inspired by God. He didn’t know I had come to him looking for a sign.

The time raced by. Eventually we ran out of questions and it was time for us to go. We packed up the tape recorder and our notebooks. Then, after pictures and thank-yous, we gave him our gift of licorice pipes. My mother thought she remembered reading somewhere that they were his favourite and I liked the idea and declared it was true. A pen was our other choice, but, it finished a distant second. You don’t give a pen to a friend.

On the way back to Woodstock, I sifted through what’d been said. No water to wine, no dead raised to life, no blind made to see. Our meeting was finished and there’d been no clear sign.

I ended up enrolled in science. I assumed I had to choose; never imagined there was room in one life for both science and art. If I’d had the courage and asked him straight up, I think Alden Nowlan might have said what I’ve come to find true — that writing is not so much a destination as a journey and the road doesn’t matter, only that you take the time to look along the way.

I’ve looked for the cassette of that interview many times through the years and had reached the conclusion it got thrown out by mistake. Imagine my excitement when it turned up in a box in my basement five moves and close to thirty years later. I dropped everything to play it through in one sitting; some parts brought tears to my eyes. Then I went to the library and signed out every Alden Nowlan book they had.

The emotion contained in his work still astounds me. One minute my heart aches, the next I’m laughing out loud. “The Bull Moose” remains a favourite. The ending haunts me to this day: "When he roared, people ran to their cars. All the young men / leaned on their automobile horns as he toppled."

[To listen to the unedited audio of this interview, check out the Radio Fiddlehead podcast.]

----

Corinne Schriver: We should ask you our first question. We wanted to start out with a really good one. We couldn’t really think of one too terribly exciting, so . . .

Corinne Schriver: We should ask you our first question. We wanted to start out with a really good one. We couldn’t really think of one too terribly exciting, so . . .

Carmen McKell: We decided just to talk about how you started writing and stuff like this. Did you always want to be a writer, that type of thing.

Alden Nowlan: OK

CS: You always wanted to be a writer?

AN: Well, I started to write things when I was eleven years old. Before that I wanted to be a cowboy. Other than wanting to be a cowboy, I’ve always wanted to be a writer. In fact, I don’t suppose it’d be strictly accurate to say that I’d always wanted to be a writer because when I was eleven years old, you see, I thought that I was a writer. Looking back at it now, I can see that anything that I wrote when I was eleven could have been written by anybody eleven years old who had wanted to write it, but, it didn’t seem that way to me at the time. And I kept on writing all through my teens and I’ve been writing, really, ever since I was eleven years old.

CS: Was there ever a point when you thought, what I want to do for a living is write or did it just kind of come about?

AN: Well, of course, when I was very young, when I was, say, oh, probably fourteen or fifteen years old, I used to, well, among the people I admired enormously then was John Keats and I used to dream romantic dreams, you know, of being exactly like John Keats. In fact, you know, if someone had told me that I would die of consumption, spitting up blood when I was twenty-six years old, I’d have been gloriously happy because when you’re fourteen, twenty-six seems to be very old indeed. It seems pretty young to me now, but, when I was fourteen it seemed old.

CS: Well, that’s what I think. The older you get the faster time goes.

AN: Sure. And then I guess because I always wanted to be a poet or thought I was a poet — I was constantly writing things — it seemed natural for me to go to work for a newspaper because in the environment in which I was, that was really the only practical way that you could make a living by being a writer.

CS: When you were young, who else did you like to read?

AN: Well I had an enormous admiration for Charles Dickens. I remember when I was very young I read an edition, I think of David Copperfield, which had nine hundred pages in it and when I finished it I was sorry it wasn’t longer and then, of course, as I got older I became interested in other writers. I used to, in fact, I’d become very interested in some particular writer and read everything of his or hers that I could lay my hands on.

CS: You liked George Orwell.

AN: Yeah. I discovered him quite later, though, in life. I wasn’t really aware of him, you know when I started out.

CS: We’ve both read 1984 . . .

AN: Yeah, right.

CS: And Animal Farm I’ve read. I like reading his books. What about the classics, like Emily Brontë and Charlotte Brontë and Jane Eyre? Did you like them?

AN: Oh yeah, you’re right. I was a great admirer of both the Brontës and when I was just a kid I used to identify with them to some extent once I found out things about them, this business of them inventing imaginary kingdoms and so on. I used to do that sort of same thing when I was younger.

CS: We just took about them in school. We took Wuthering Heights.

AN: Incredible women, really. There was a whole family of them, all writing except for the brother who was a painter to some degree. All the sisters wrote. I haven’t read any of Anne Brontë’s books, but...

CM: Did you find it easy to get a hold of reading material when you were young? Like did you read a lot, like more than any normal kid would?

AN: Oh, yeah, yeah. Oh, yeah, I read (sound of tape recorder being moved). Should I sit somewhere else so it’ll pick me up better, do you think?

CS: I think that’s OK. I was just wondering. I just thought I’d set it a little bit closer. So why did you write? What made you?

AN: Well, I think to some extent it was for the same reason that some lonely little kids invent imaginary playmates. I was very much alone and I would be just as you probably heard of little kids who have imaginary friends.

CS: I like to write. I keep a diary and I find writing is a good outlet. If something’s happened you just write it out and . . .

AN: There’s a wonderful line in Anne Frank’s diary where she says that “Paper’s more patient than people.”

CS: We’ve both read that too. Anne Frank.

AN: That’s a beautiful book, isn’t it?

CS: Yeah, I really liked it. I read it about four times.

AN: “Paper is more patient than people.”

CS: True, very true.

CM: So, do you consider your writing as work?

AN: Yeah, well, to begin with of course I didn’t and then there was a bigger period in my life when I was working for newspapers for a living and writing poems and short stories besides, and, during that period I suppose I considered the newspaper writing work and the other, though, wasn’t, but, I suppose in a sense that I consider it all work now, but, that doesn’t mean that all the pleasure has gone out of it.

CS: I suppose since you do it a lot for a living, it’s work in that sense.

AN: Yeah. That makes a difference. You can’t always choose when you want to do it in the way that you can when you’re . . .

CS: How do you? Well . . . you write for the Telegraph every week and you write in the Atlantic Advocate, right?

CM: Where does your inspiration come from?

CS: You just write about stuff you’ve experienced during the week?

AN: Mostly. Practically everything I write in every field begins with something that’s happened to me. Walter Learning who used to be the artistic director of Theatre New Brunswick and I wrote the stage adaptation of Frankenstein and I told some people who’d invited me to the stage version of the book that I’d written the story of his life as though I was the creature, and while, in a sense this is an exaggeration, there also is a large element of the truth in it, because, I don’t think that I could have written the part of the creature — I prefer to call him a creature than a monster — of the creature so well, had I not felt at some periods in my life almost as total a sense of rejection as he felt, except he felt it permanently while for me it was temporary. But I think everybody, all of us momentarily at some time or another feel a rejection as total as that, you know, it’s just that the creature feels it all the time, so, I think that any writer really has to begin with what he or she has felt and experienced.

CS: We had an English teacher who always stressed that; that to be a good writer you have to write about what you’ve experienced. You can’t write about something that you don’t know about; that you haven’t experienced in order for it to turn out right.

AN: But, mind you at the same time you needn’t to have had the total experience to understand it. Using this Frankenstein creature again as an illustration, had I been Mary Shelley writing the novel or my sojourn on the stage adaptation, I don’t think you can write it unless you felt that alienation, that sense of rejection, that sense of being totally shut out, but, it isn’t really necessary for you to feel it to the extent that the creature did, to the extent you know where you are going to strangle people.

CS: If I told you I wanted to be a successful writer, what could you tell me for some advice. What does it take to be a successful writer?

AN: One thing that’s awfully important, and, possibly the thing that is the most important of all, I think, is to try to learn to distinguish what you genuinely feel about something from the way in which you think the people around you expect you to feel, which is really much harder to do than it sounds, and, I don’t think any of us are ever completely successful at it. It’s like the Hans Christian Andersen’s story of the Emperor and his clothes. If enough people tell you that the Emperor is wearing beautiful robes, and, you see that he’s naked, you’ll think that there’s something wrong with you, and, you won’t want people to know what’s wrong with you, and, therefore you won’t say that he’s naked, you’ll be saying, “Oh! Those are beautiful robes,” so people won’t think you’re crazy. Then, of course, it’s obviously necessary to be a writer to have a fascination with words and language.

CS: You must be, well, people are always saying you can’t really make it as a writer, it’s a very hard thing to do. You have to kind of work up from the bottom. It’s a really difficult thing to achieve. Would you agree with that?

AN: Well, other than if you’re someone like Harold Robbins or Arthur Hailey who make enormous amounts of money, as a writer, just as, like an actor, or, as a musician, really, or almost anybody in the arts, you’re never going to make the same amount of money for the same amount of effort as you would make in most of the other professions, but, on the other hand, you probably derive a great deal more satisfaction. Somebody has said the greatest pleasure in life is to be paid for doing something that you’ll do for nothing anyway. A good example of this, are actors, who unless they’ve really made it big and have a successful television series or something, are working in many cases for very little more than the minimal wage and are constantly away from home, so that they live in Toronto, you know their husband, or, their wife, or, whoever they love, or, their children are there, and, they’re staying in that cheap hotel in Regina or in Fredericton, and yet, oh, I think very few of them would ever trade it for anything else because as soon as they step on the stage there’s a world of complete magic, you see, and suddenly you can be King Lear or a murderer or a crime lawyer, fancy anything . . .

CS: That reminds me of something — you were analyzing someone’s book and you were saying that when you read it a chill went up your spine. You were saying that’s the best applause an author can ever have.

AN: I think so. Yeah. That’s the thing, too, about being a writer, or a painter, being an actor. It’s a thing that I used to talk about with the painter Tom Forrestall and he said, and I think there’s a good deal of truth in it, that people who are writers or dancers or actors, or, in his case, painters, are, in a sense there’s a part of them that never grows up. He used to say of himself that when he was six years old, all the other six year olds used to draw pictures and colour. He just kept on doing it. Well, it’s an oversimplification, but, I think it does contain an element of truth.

CM: So, do you think today that this creativity and imagination is lost with children as they grow up with television and all this technology, science and everything?

AN: I really don’t know. I’m not really in a position to know. I don’t really . . . it’s so hard to tell.

CS: We wanted to ask you, too, about our generation. When we look around at everyone, everyone seems really irresponsible and they’re uncommitted and at school there’s no school spirit; big basketball game and four people show up. What do you think of our generation? Is it a lot different from generations before us, or, has it always been like this?

AN: Well, I don’t know. One thing that I tend to fall back on in respect to things like that is a thing that George Orwell said in one of his essays to the effect that each generation has its own kind of truth and in the course of this, in fact, he says that the person as he gets older shouldn’t try too hard to keep up with changing attitudes for if he does he defaults to his own experience. A specific example that I can think of in this case is there are a great many things in which I have completely different attitudes about than my son, who is in his late twenties, because, I was born in the depression when it was sort of inoculated into you that you could conceivably starve to death if you didn’t eat everything on your plate. If there were two beans left you must save them, you know, this sort of thing. Whereas, of course, he was born in the fifties. He came along during an affluent time, and he has a completely different attitude toward things. Well, for instance, people of my generation tended if they got a job to endure almost anything rather than...because they felt, really unrealistically, because at the time that I was a young man things had changed enough, there were enough jobs to go around, but, it had been so pounded into me by my father’s generation that I would have held onto that no matter how bad it got, thinking that was the only job there is, whereas, he grew up in the seventies where you could quit one job and there are three other people asking you to go to work for them.

CS: We’ve read a lot about abortion, too, that you’ve written. We saw, just a few weeks ago, that film — the pro-life film on abortion and it was really mind opening. Do you think abortion would have like . . . how am I going to say this? One reason, do you think, for our generation’s irresponsibility is if you get pregnant you can have an abortion or if you get married you can have a divorce, so easy, all these little things, that’s probably a big factor, do you think?

AN: Well, the abortion thing is so complex. One of the things I find that’s disturbed me in my own case is that usually when I express any view on it I am supported by a lot of people that I disagree with. The thing that I find, maybe because I don’t take the stand that no abortion under any circumstances, the thing that really disturbs me the most is the approach is that we’re making it seem like a casual thing. I was talking to the bishop the other day, the Anglican bishop and he said that he felt the reason why there was so much extremism on the issue was that once you’ve taken the extreme position you no longer have any responsibility for it. From one extreme there’s no abortion under any circumstances, to the other extreme there should be unlimited abortion, and you’ve washed your hands of the whole issue, but, as soon as you take the middle ground, either you, or, somebody else has assumed responsibility for deciding when the abortion is not justified. He had an interesting way of putting it, particularly interesting coming from the bishop. He said it was a question on which each of us must simply consult our conscience, because, I think in the final analysis it’s one of those things that only God can answer.

CS: But a lot of people are too selfish. I mean they just think about themselves.

AN: Yeah, right. Of course it is. But it’s fascinating the way all these attitudes have changed during my lifetime, and, I think a great many of them for the better.

CS: The war had a big effect on you too, didn’t it?

AN: Oh yes. For one thing, I was just the right age to make a hero of the soldiers. You see, I was just twelve years old. All my cousins who were eighteen, nineteen in the city were going around in uniforms and the little village in Nova Scotia where I lived, one of those places where, if you drive through it and blink you don’t see it at all.

CS: Woodstock.

AN: No, no. Much smaller than Woodstock. Oh, we’d have thought Woodstock was a city. No, it’d be more like Coldstream or Debec, probably smaller than Debec. But they built there during the war this training school, so, suddenly there were all planes in the air and these young airmen all over the place, and, also they had the demarcation point where the soldiers used to stay until they boarded the ship in Halifax to take them to England and so at this very impressionable age I was constantly surrounded...all the little boys, we were all disappointed when the war ended because we all wanted to be Spitfire pilots.

CS: Have you ever travelled over to . . . well, you’ve been to Ireland, I know that. Have you ever travelled to any other European countries?

AN: Just England.

CS: You’ve never been to Holland or Germany?

AN: No.

CS: Have you ever had any urge to go over there?

AN: Yes, I’d like to. Yeah.

CS: I would too. So probably we should get on to our Maritime questions.

CM: We wanted to know what are some of the advantages and disadvantages of being a writer in the Maritimes?

AN: I think we vary a lot depending on the person. I think some people who are writers would be very unhappy here, simply because they’re the sort of people who require, or, need a lot of association with other people who write.

CS: You don’t get that here?

AN: You don’t get really as much of that here as you would, say, in Toronto or Vancouver or Montreal, though there are quite a few writers here in Fredericton.

CS: We’ve written to quite a few writers here and gotten replies from them.

AN: Yeah, right. There are quite a few in Fredericton.

CS: So what would be some advantages?

AN: I think one of the advantages is that things are on a very human scale here. You know, there are some examples that always occur to me when someone asks me about the advantages and disadvantages.

CS: A common question?

AN: Well, it’s a good question. One example I’d have is that a number of years ago at three o’clock in the morning I was walking down Queen Street and immediately in front of me were the premier, the mayor, and Stompin’ Tom Connors arm-in-arm. I can’t imagine walking down Yonge Street in Toronto and seeing Bill Davis, you know, and Paul Godfrey and Gordon Lightfoot arm-in-arm. Then also the same day that I met the Dalai Lama here in town I almost ran into a wild bear just a few miles down the road. So, you can almost run into a wild bear and meet the Dalai Lama on the same day. When the Prince of Wales was here training to be a helicopter pilot I went and talked with him. I’m sure that if I’d been in Toronto, I’d never have had the opportunity.

CM: So do you consider yourself a regional writer?

AN: I hesitate to, because, so often the word is used in kind of a condescending way. When people say that so-and-so is a regional writer, you know, it’s sort of like saying that he’s playing in the minor leagues.

CS: He can only relate to people in his region.

AN: Exactly. Right. But, on the other hand, I think all the great writers have been basically writers who have written about their own place and time.

CS: Their own experiences.

AN: Yeah.

CM: Do you consider New Brunswick behind the times compared to the rest of the country?

AN: I suppose that in a way that is, but, I think that for our leaders there’s a sense of an advantage to it. I think it was Marshall McLuhen who said that we have a wonderful chance in the Maritime provinces to skip the twentieth century entirely and jump right from the nineteenth to the twenty-first, and, it’d be a great thing to do because the twentieth century is a mess anyway. I don’t think we could ever do it because the people who guide our affairs seem to want more and more to be like the rest of the world. It seems to me that when we see what dust and pollution does to other places, that if we don’t have it, why get it? That sort of thing.

CS: What’s the advantage of being up to date anyway?

AN: Right. Exactly.

CS: Do you find that since you live in the Maritimes, does that have a big effect on your popularity throughout the rest of Canada and the United States? Knowing you live in the Maritimes and write in the Maritimes and write about the Maritimes, are those outside the Maritimes more apt not to bother reading anything you write?

AN: No, I don’t think so. No. You miss out on some things simply because you don’t, in the actual course of your day or your week, run into as many publishers or producers as you would in Toronto. If you were a Toronto writer you might simply drop in for lunch and someone who was publishing a magazine might simply see you and so an idea for an article is right in front of you. You might even get better reviews because quite often the person reviewing your book knows you and he knows if he writes a bad review, he’s going to meet you face to face at some party, you see. On the other hand, whereas for some things like freelance journalism, magazine articles, and that sort of thing, it has, on some occasions, been an advantage to me, because, I’m almost the only magazine writer in New Brunswick, the only true Nova Scotian I think.

CM: So have critics ever told you anything interesting or helpful to you?

CS: Do you ever listen to them?

AN: Well, yeah. Some of them have, but, the trouble of it is that no matter how your mind tells you to be objective about these things, the act of writing or of painting or of being an actor is so personal that’s it’s very difficult for you to distinguish criticism of what you do from criticism of you as a person and so go crazy if you get too obsessed with it. Now I found with myself I would be prouder of mine if it was a bad review than a good one, because, if you showed a good one it seemed to me that it’s sort of boasting, and, I suppose the other way it’s like you’re begging for sympathy. The last while I’ve been trying to avoid them altogether, but, I believe that’s pretty hard to do.

CM: So, where do you get your inspiration or your encouragement to write?

AN: Oh from almost everything that happens to me. Really, I’ve got the ideas for stories and poems from things I’ve overheard on planes, things that people say to me. If someone is a writer and I hear them tell stories, I tend to try to avoid using it because I feel they might want to use it themselves, but, everybody else I feel free to steal any of their experiences without any scruples.

CS: This is back to your childhood, again. When you were younger did anyone ever encourage you to write?

AN: Oh no. No. In fact, completely the opposite. Because you see it was a very kind of working class background. My father worked in sawmills and the woods all his life and I was even self-conscious about reading books where he was. If I’d seen him come in the room I’d automatically hide the book that I was reading. He’d have thought, probably, that it was alright if my sister read books, but, not what men were supposed to do. If he had known that I wrote poems, he’d just as soon I started wearing lipstick and fingernail polish. It was all the same to him.

CS: We had a short story in one of our books in English, I think, last year “The Fall of a City”. Did you...the little boy...Was it his uncle who destroyed all the buildings? Was that you?

AN: Oh, yeah. I used to invent things like that. Earlier on, I was saying which reminded me of the years later when I heard about the Brontës doing the same things. All the little details in the story weren’t true, but the business of inventing the cities and so on. I even used some of the names, as a matter of fact, of some of the kingdoms that I invented as a kid in the story.

CS: What about at the end? Is it the uncle that destroys the . . . ? Like, I kind of got out of it that the boy’s imagination was being destroyed in a way.

AN: Incidentally though, not long ago I’ve been doing some short story reading to put in a book and I thought I might put that in it. I changed the ending so it goes up to where it goes now where the uncle destroys the city and the boy is really shattered, but, then I’ve tried a new ending where he starts creating it all in his mind. That’s where the uncle can’t get at it.

CS: That’s good, because, the way it ended before you felt the poor boy is going to be ruined for the rest of his life. So that’s good. Glad you did that. We thought we had all these questions here and now we’re whizzing right through them.

CM: What do you feel about the present educational system in New Brunswick?

AN: I don’t honestly know enough about it, you know, to be entitled to have an opinion, and, then I received so little formal schooling myself that I always feel absurd expressing opinions about how the school system should work.

CS: What do you think about education? You quit school when you were fifteen, right? Do you really think it does much good — education?

AN: Earlier on in my life there were times I had reason to regret not having gone farther in school for the straight forward reason that when I was in my twenties, I could have had jobs that were more congenial, that would have paid me more money, ones that I would rather have done, had I gone on and gone to high school and gone to university. But at this point in my life, looking back on it now, the main thing that I think I missed, which I know I missed, which would have made me much happier then, and, probably would have benefitted me all the years since and even now, would be for instance, well, say that had there been a regional high school in the area in which I was, as there is now and if they’d bussed everyone in there, almost inevitably in a population say, oh, of probably six hundred kids there would have been at least a half a dozen who were as freakish as I was, you see, so I wouldn’t have been as totally alone as I was, and, the chances of me meeting some teacher who actually actively encouraged me in writing would have been much greater than it was going to the one room school.

CS: You could look at it the other way, though too. If you’d done that, it might have turned out totally differently.

AN: Oh, I’m sure it would have.

CS: You might not have, well, it’s hard to say what might have happened. I’m not even going to think what might have happened.

AN: That’s true. Mark Twain all his life was fascinated by how small events could create great happenings, how if you arrived at an intersection thirty seconds earlier you’d have been hit by a train, that sort of thing. In his old age it got so it bothered him so that he wouldn’t go outside the house, because, he was afraid of doing something that would change the whole course of history, because, everything you do presupposes a whole set of changes.

CS: A little thing can make a big difference. Do you consider yourself a man who lives in the past, present or future?

AN: Oh! That’s a good question. Yeah. That is a good question. That’s a very good question, because, well, I try to as much as possible, to live in the present. I’ve always liked the things the Zen Buddhists emphasize about the now, the here, but, inevitably, I don’t think it’s a thing that we have complete control over. That when you’re very young, in a kind of way, you live, oh gosh, well to some degree, it varies depending on what mood you’re in, anywhere from fifty percent to seventy-five percent in the future, and, you have this eternal hope that no matter how bad things are there’s an infinite number of choices ahead of you, whereas, inevitably, when you get to be fifty, as I now am, without any matter of choice you do live to a certain extent in the past. One thing that struck me about this is that time periods that seemed infinitely long to me when I was your age, now seem comparably short. I first came from Nova Scotia to New Brunswick when I was nineteen, and, when I was nineteen I’d hear people talk about something that happened twenty years ago. Well, as far as I was concerned it might as well have happened a hundred years ago or two hundred years ago, whereas, now something that happened twenty years ago, you know, seems quite recent to me. So, it’s not something you do by an act of the will and that’s the thing you have to fight against or else you become a terrible old fogey, you know and you’ll find yourselves saying things like, “When I was their age...” It’s awful. Dreadful. Dreadful.

CS: Being a writer you kind of live in the past anyway, don’t you?

AN: Right. Someone said “All fiction is a story book,” all fiction, really, because there’s more of an immediacy with poems. Most people who write fiction it’s about something that happened five, ten or more years...

CS: You just write a poem whenever the mood strikes . . .

AN: And also there’s the thing in fiction that certain types of things that you’ll tend to set in the past even if the thing that caused you to write the story happened in the present, for instance, if the idea occurred to me right today that would involve someone, say, your age I would probably set the story in the 1950’s simply because I think I could write reasonably good dialogue at the way people your age talked in the 1950’s. If I attempted to write dialogue for the way people that age speak today, it would probably just end up sounding silly, because, the rhythms of speech have changed and the slang terms would have changed completely.

CS: Yeah, they change every day.

AN: Yeah, almost from day to day. That’s right.

CS: My little sister’s at one school and they talk completely different than at our school.

AN: I bet they do.

CS: It’s funny. I feel like I’m getting old. I’m seventeen and I think my sister's twelve.

AN: Yeah, I bet that’s true. It always sounds so silly when it’s wrong, doesn’t it? Not so much now, but oh, back say ten years ago when there were enormous number of students in Universities who wanted to be poets or even imagined they were poets, a lot of excitement, many more poetry readings then than there are now, and there were a number of poets of my age and some of them older, some of them ten or fifteen years older than I am, who, as they were giving readings at universities would attempt to talk in the same way as the students talked. Invariably they always sounded silly, but, they didn’t know it. And also condescending. They not only sounded silly, but, even condescending.

CS: You write about everything. Do you ever feel like your whole life is exposed for everyone to read? Does it ever bother you that everyone knows so much about what’s happening?

AN: There was a period when it would have bothered me terribly, because, you see when I started writing anything that I had published was published in magazines with very small circulations, besides which, none of the people among whom I lived read any poetry anyway or really any fiction, so, I never actually encountered anyone who read anything that I wrote. Well, then when it first began to happen that the things that I wrote were appearing in larger magazines or in books and I was associating with people who did read them, there was a period of a year or so when I found that I didn’t write anything at all, because, I felt so kind of exposed, as though someone were reading my diary over my shoulder, so, I really deliberately schooled myself and disciplined myself, which I think you have to do under those circumstances, so that in the work that’s written I always think of the narrator of the poem, the ‘I’ of the poem as the protagonist in the poem rather than ‘me’ just as an actor speaks of the role he plays as ‘him’ rather than 'me' and in a sense this is not just a trick; it’s true because the self that you do project in the poem isn’t literally you. In a way, it’s a kind of idealized self, or, just a projection of yourself, and, quite often in order for the poem or the story to have maximum impact you carry an emotion or an event much farther in the poem or the story than it went in real life. The classic example is Dante dedicating his great poem to Beatrice and I think the researchers now generally agree he only saw her once in his life.

CS: So would you describe yourself, then, as a private person?

AN: Yeah, I think that I’m . . . I hope what I’m going to say isn’t too convoluted, but I think that it’s true. I think a great many people who are writers are people who were, perhaps, inherently extroverted, but, because of something in their childhood or youth were forced into kind of an unnatural derision. I don’t know if that makes sense to you. Well, to give a more specific example, I’ve noticed that at things like parties, invariably, the actors who have a chance to do all sorts of things on stage, tend to sit quietly, many of them very shy people. They sit quietly, sort of murmuring monosyllables to one another, while many of the writers will be performing madly, you see and there’s sort of a curious irony about that.

CS: I always kind of pictured writers as more, like quiet and secluded. That was always my picture, my stereotype.

AN: Well, there’s truth in that, too. There’s kind of a conflict between most people who are writers between being a private person, you know, and wanting to sort of say, “Hey, world! Look at me. Look, Mummy! No hands!”

CS: You’ve written a lot of stuff that’s out for the public to read and people must kind of get so they know you. In a way I feel like I know you, I’ve read so much. It must be kind of funny for people to come up and act like they know you when you don’t even know them.

AN: Yeah, but it’s great though in many ways because you don’t have to bother really with any small talk with them, and, it’s really great though because they feel like they know you, they tend to be very open with you. You know, people who’ve read a lot of things that I’ve written who talk to me tend to speak to me very openly, rather than the way they would speak to a stranger.

CS: And you don’t mind that?

AN: Oh no. I love it.

CS: That’s good. What about all these little interviewers who come up and ask for interviews?

AN: Well, it varies. Usually I enjoy it. The only interviews that really put me off are the ones done by professional people, like for radio, say, or television or magazine articles, are the ones who come prepared with complete preconceptions, a mould that they’re going to fit me into, and all of their questions are aimed at enlisting answers that will fit me into that. The last time I was in Toronto I was interviewed by a fellow for the magazine Books in Canada who actually admitted to me that he’d already written the last paragraph of the article which was to the effect that I had said that I couldn’t be happy in Toronto because I couldn’t see the sea. I said to him, “You can’t see the sea in Fredericton either. At least, you can see the lake in Toronto.” Also I get annoyed with interviewers, you know, from radio or television who haven’t read anything that I’ve written, you know, because it seems to me why do they bother wanting to interview me? I might be the world’s worst writer as far as they’re concerned if they haven’t read anything.

CS: Do you get a lot of offers for interviews from students?

AN: Oh yeah. Generally I love it. Let’s face it. We all love it. Just to sit there and blah away about yourself. It’s wonderful. Ha, ha! Anybody loves it. Ha, ha, ha!

CS: You can get ready listeners.

AN: Ha, ha, ha.

CS: . . . put an ad in paper — anyone who would like to listen to me talk, be available this afternoon...

AN: Ha, ha, ha.

CS: What do you think? Do you think writing is a glamourized occupation? Everyone seems to think the writer . . . it’s wonderful. Do you find that?

AN: Oh yeah. Sure. The writers themselves contribute to it. Yeah. That’s the way I always thought of it. I always thought of, you know, when I was, say, sixteen or seventeen years old, I hadn’t met any poets. In fact the first poet that I met face to face I was desperately disappointed with him because he seemed so bloody ordinary. Since then, I’ve disappointed whole generations of younger poets who found me ordinary.

CS: I’d like to ask . . . I’ve always liked Robert Frost poetry.

AN: Yes, I do too.

CS: Do you like Robert Frost?

AN: Oh yeah. I’ve read his poetry a great deal. He’s a marvellous poet. I’m reading about halfway through a biography of Robert Frost. I read a wonderful thing in there which I’d never heard of before, that he decided, oh, I don’t know how old he was when he made this decision, we’ll say probably twenty-three or twenty-four, that life had no more meaning for him, and he was going to kill himself, but, found he had such a romantic conception even then of the poet’s role that he didn’t think that he could just jump off into the Charles River in Boston where he lived. He thought to himself where would be the most appropriate place to die. And he decided the best place to end his life would be the place known as the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia so he bought a ticket on the train and went down and walked out into the Great Dismal Swamp where he eventually decided that he wasn’t going to kill himself. But it seemed such a wild and romantic vision — right up to the minute you killed yourself you’re still doing it.

CS: What about Edgar Allan Poe?

AN: Oh! I still like him. But I was really, when I was teenager, oh, I was mad about him.

CS: Everyone must go through that stage where they like Edgar Allan Poe.

AN: Yeah, that’s true. Some of them that I read then sticks in my mind so well that I know parts of it off by heart: “Oh! The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne without reproach, but, when he ventured insult, I vowed revenge.” Of course he buries him alive or something. People were always being buried alive. Then there’s something about the poems. They had wonderful rhythms in them, too, that appeal to you when you’re young.

CS: “The Bells.”

AN: Yeah, that’s right.

CS: We tried to memorize that. Through lunch, we’d get going on that.

CM: I read an article of yours. It was about your cat, Flash, when he got run over, and, you were talking about barn cats, how nobody owns or possesses them. Like, could you kind of classify yourself as that kind of a person? A barn cat?

AN: Oh! I identify with barn cats. I identified with Flash. I felt very bad when he . . . I got a wonderful letter from some girl who was in Perth Andover who wrote me a letter of sympathy. She said “My friend tells me I’m silly, but, I wrote anyway,” and I wrote back and said, “Tell your friend that she’s the silly one.”

CS: She was just young?

AN: Not very old — fourteen or fifteen. Said she had a dog that was killed and she could understand my problem . . . It was nice of her. Old Flash was too adventurous. He got hit by a car outside the house.

CS: This isn’t a very good place, really, for a cat.

AN: No, no. It’s alright for this cat because all she does is sleep in the house.

CS: We have a cat and she’s twelve. She’s really getting on. We live right by the road, too, right on Connell Street which is a pretty busy place. She lives on and on. My mother keeps hoping that one of these days she’ll wander out, but, no way. She’s really smart. She’s too smart for that. She’s grown up with my sister who’s twelve.

AN: She’d seem very old to her. We had a cat that lived to be fourteen and she eventually died. And my son had tears in his eyes about her dying even though he was in his twenties, because, you see to him, we got her when he was about four years old, and she seemed sort of infinitely old, not just fourteen. She’d always been there from the time he was a little boy before he went to school, to all the time he went to school, to the time that he grew up and became a young man, so it seemed to him as if she were a thousand years old.

CS: And cats are always there. They’re not there one day and . . . well, some of them are. They take off. What about kids? You like kids a lot, don’t you? I wanted to ask you what you think the characteristics of a good parent are?

AN: Oh gosh. Well, I always thought of myself that I’d make a much better grandparent than a parent.

CS: Just take them out for the good stuff.

AN: Being a parent is such a terrible role because it’s such a phony role in many ways that you find yourself in. For one example, you’ll find yourself expressing very emphatic, heavy attitudes about things that you actually think are probably funny. Then you’ll be forming an alliance with some school principal you think is an ass, saying you have to do what you’re told. You can’t very well say that the principal is an ass, when I’d have done the same thing, so there’s all that sort of play-acting. It goes with the part. You have to do it. But it’s such an odd relationship too, fascinating thing, that as your children grow up, you see them as an adult, but, you see within them all these previous selves right back to the times they were babies or little children. They’re all there. So, in a sense my son has always seemed infinitely younger to me than the other people his age. I have to fight against letting him know. That would be fatal.

CS: I always used to think being a parent’s no big deal. But the older you get, the more you find out hard it is. I’m the oldest in my family and I can see my sister and brothers, but I’m glad I don’t have to raise them. I couldn’t cope. It’s really a big responsibility.

AN: That’s true. If you thought about it enough you’d really go bonkers

CS: Probably to wrap things up, then, would you . . . my favourite poem of yours that I’ve read is “The Bull Moose.” I like that. Would you tell a little about that? How that came about?

AN: This was back when I was working for the newspaper in Hartland, there was actually a moose wandered into town and eventually was shot, which was the thing that bothered me to write the poem. Of course, I elaborated it a great deal, sort of identifying the moose even with Christ . . .

Comments

Alden Nowlan

Interview with Alden Nowlan

Alden at home

Add new comment