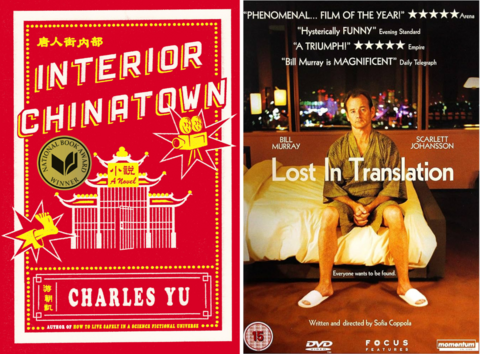

Lost in Translation (film by Sofia Coppola) and Interior Chinatown (novel by Charles Yu) by Francis Chang

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle posits that it is impossible to know the exact location or nature of a particle at any particular moment because the act of observation itself causes a slight shift in position of the observed subject. The resulting alteration in trajectory from the present moment will magnify over time, until the next act of observation and reflection.

As someone in the thicket of middle age, I wonder how much my recollections of the past shift my understanding of the world. Even in this later stage of life, I still obsess over the questions “who am I” and “what is my place in this world”? It is with this mindset that I rewatched the movie Lost in Translation and read the novel Interior Chinatown.

The movie, written and directed by Sofia Coppola in 2003, follows a young, newlywed American woman, Charlotte, played by Scarlett Johansson, and an aging movie star, Bob, played by Bill Murray. Each of these characters are lost in their respective lives, searching for some kind of connection and understanding. We observe them navigating the surreal vicissitudes of Japanese culture within a framework of ennui, like jetlagged ghosts haunting the plush, quiet luxury environs of the Park Hyatt hotel, Shinjuku, while the pulsating lights and energy of Tokyo beckon outside.

When the movie first came out in 2003, I was six years into living life as an expat in Hong Kong, trying to figure out where home really was. Although I am Chinese in ethnicity, I was born in Tokyo and grew up in Vancouver, Canada. Based on my exterior appearance, I look like someone from Northern China, like my father, but my speaking voice gives me away as someone from the West Coast. Growing up in the late seventies and eighties, I sounded and thought the same as my white classmates. But when I looked in the mirror, or as others might point out, whether innocuously or aggressively, I didn’t look like other “Canadians.”

I have no facility with different languages, Asian or otherwise, so when my wife and I moved to Hong Kong in 1997 for jobs, I felt incongruous. Locals couldn’t understand how someone who looked like me couldn’t speak Cantonese. Without a good understanding of the language of Hong Kong, or the feeling of belonging in Vancouver, I had found that the safer mode for my existence was to observe others, to be part of the background while figuring out how I was meant to fit into these worlds.

I found Lost in Translation alluring and hypnotic the first time I watched it. Hyper-modern Tokyo provides a sleek, sometimes overwhelming, often disarming backdrop against which these two characters, each dealing with their own existential crossroads, try to navigate their melancholy. Coppola’s direction and script, full of small, ephemeral episodes, give the movie a distinctly quiet, contemplative, even romantic aura, like going for a nighttime walk with an intriguing stranger.

I identified with how language and cultural barriers could make ordinary things seem slightly murky, off-kilter. At the time the movie was first released, my wife and I were in our early thirties with three young kids, just starting to get settled into our careers. On the surface, it looked like everything was coming together, but on the inside, we were still trying to figure out where life was going to take us without an instruction manual for what we were doing. Where was home, who were we?

In the next 15 years, we ended up moving back and forth between Vancouver and Hong Kong twice, each time living a new version of “what if,” shifting the narrative and placement of our lives, and those close to us. And so, a few years ago during a long haul flight I saw that Lost in Translation was on and watched it again. My second time watching the movie, I felt myself experiencing it on two parallel tracks. One track was a trip through nostalgia, with the sudden recall of my younger feelings of being lost and trying to figure out where my life was going. The other track was a different awareness of my mortality, staring at the fast approaching off-ramp of middle age. My older self felt uncomfortable with the realization that I was now around the same age of Bob (Bill Murray was in his early fifties when he played the role), with my children now around the same age as Scarlett Johansson was – seventeen - when she played the role of Charlotte. This discomfort shifted my nostalgic view of the movie, causing me to question things I thought I had understood. As a parent watching your kids become young adults, do you admit to them that even as you get older and have more lived experience, you’re still startled by life’s ambiguities? I was experiencing my own moment of Heisenberg uncertainty.

Nonetheless, the elliptical and subtle nature of Coppola’s filmmaking came through - life is about finding those small moments of connection; that instant of recognition, where even in a strange place, one can feel just a little less alone.

The novel Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu makes for an interesting counterpoint to the movie. Yu’s novel is structured, for the most part, as a script for a TV crime series, with the protagonist, Willis Wu, playing the part of “Generic Asian Man,” always part of the background, never a main character. The novel interrogates how popular American culture has marginalized the experiences and narratives for Asian Americans, usually fitting them into a few, easy categories such as delivery guy, laundry store owner, victim.

The characters and situation of Interior Chinatown are an inverse of Lost in Translation. Chinese Americans protagonists, who may be second or third generation in California, dealing with an internal sense of conflict - being American but observed by others as foreign, not really belonging. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle as existential conflict, with Interior Chinatown representing both a metaphorical and physical space. As the character Wu laments:

I have to talk with an accent because no one can process what the hell to do with me. I’ve got the consciousness of a contemporary American. And the face of a Chinese farmer of five thousand years ago. Asian Man. It’s a fact. Look it up. No one likes us. (Interior Chinatown, page 166)

Through sly humour and often times startlingly beautiful passages, the book asks readers to consider the question of who we are if society is not immediately willing to give us agency. For example, consider this passage about an older Asian business man singing the John Denver song “Take Me Home, Country Roads” at a karaoke bar filled with “drunken frat boys and gastropub waitresses.” The scene could be fraught with potential for jeers and humiliation, but instead:

… by the time he gets to “West Virginia, mountain mama,” you’re going to be singing along, and by the time he’s done, you might understand why a seventy-seven-year-old guy from a tiny island in the Taiwan Strait who’s been in a foreign country for two-thirds of his life can nail a song, note perfect, about wanting to go home. (Interior Chinatown, page 66)

In telling such a specific story, Yu reaches for a universal theme of individuals who might feel alienated in the world, searching for their own place in it.

For me, Interior Chinatown is a companion piece to Lost in Translation. They are both about individuals trying to find themselves while navigating two different cultural sensibilities and experiences – one rooted in American movies and TV, the other in fast changing East Asian societies. In watching Lost in Translation, I can relate to that feeling of what it means to straddle different worlds. When the gift of travel to a different place offers the opportunity for one to ask: what if I had chosen this path to live somewhere else? Who would I be? “Interior, Chinatown” makes me reconsider how these questions may be restricted by the perception of who counts as a main character.

Ultimately, I think both works suggest the answer lies in the fleeting moments of connections one can find in life. Within the context of Heisenberg, at any given moment one may not be entirely sure of where one fits or who one is within a particular place, but we can always be sure when we have connected with another. For me, my children have provided me with many small, yet extraordinary, moments of recognition. As the character Wu observes:

… There are a few years in a family when, if everything goes right, the parents aren’t alone anymore, they’ve been raising their own companion, the kid who’s going to make them less alone in the world and for those years they are less alone. (Interior Chinatown, page 157)

I invite you to watch (or rewatch) Lost in Translation and read Interior Chinatown and, together with these characters, find your place and connections in an ever changing world.

— Francis Chang is a Chinese Canadian who was born in Tokyo, grew up in Vancouver, worked in Hong Kong and returned to Vancouver again with his family. Chang previously practised law for more than 25 years and now focuses on writing, as well as leadership coaching and consulting (fc2focus.com).

You can find Francis Chang's story "Absent Fathers" in Issue 301 Autumn 2024. Order the issue now:

Order Issue 301 - Autumn 2024 (Canadian Addresses)

Order Issue 301 - Autumn 2024 (International Addresses)