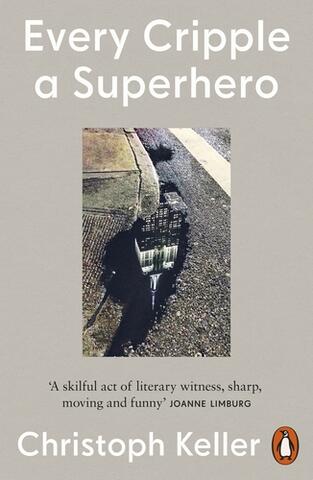

Every Cripple a Superhero by Christoph Keller is a great example of a hybrid memoir. There are photos, poems, flash prose, cultural criticism, and a Kafka-esque surrealist short story interspersed throughout the book. An earlier and slightly different version of the manuscript was first published in German in 2020.

Keller weaves subjects in a masterful way. Each piece of short prose is complete by itself, a snapshot of memoir. Read as a whole, the storylines weave and build powerful themes throughout the narrative. Like the theme of superheroes as an allegory for disability, both as empowering role models and as a metaphor for the superhuman skills disabled people need to navigate life as a group that is either invisible or hypervisible. People who, as Keller details, must approach each airline booking or museum visit like preparing for a Big Bad supervillain fight, armed with knowledge of industry and government regulations, self-advocacy skills, and multiple phone calls to make sure vital access supports will be in place. Only to find upon arrival gruff, rough workers instead of the kind and patient staff you were assured of before you paid. Or an “out of order” sign askew on a museum’s elevator door, making you navigate a maze through the back end, wending and winding for almost an hour, to finally arrive at the exhibit that was supposed to be a short elevator ride away from the entrance.

Keller is a wheelchair user who was fourteen years old when he was diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy, a progressive disease that attacks the muscles so they weaken and shrink. For years as a part-time wheelchair user, Keller switched between the monikers “Walking Me” and “Rolling Me” to describe himself. Walking Me often went on first dates, though he says his love life was more successful when Rolling Me got to initially charm love interests. Perhaps Rolling Me felt more comfortable and confident, he says, and so was able to connect better with his dates rather than grimace in pain from the strain of standing and walking. Keller describes how he returned home after one date--the woman in her car and he walking along the sidewalk to his front door--when his legs gave out from the stress of over-use. He never heard from his date again. He jokes that he’s not sure if she’d witnessed his “shame” or just wasn’t interested.

This humour rolls throughout the book. Each time I picked up the memoir, I was riveted by Keller’s voice and dispassionate and sardonic descriptions of casual and not-so-casual ableism, and also disabled joy and meaning making. This text is a testimony to the indignities so often thrust upon disabled people. I hope many readers are so changed by Keller’s words that those changes ripple out to create, superhero-like, a much more accessible and inclusive world.

Every Cripple a Superhero also showcases Keller’s spectacular photography, which witnesses New York City’s curb cuts that are often full of pot holes and deep cracks that are dangerous for many, including pregnant people and anyone on wheels. What he initially intends to be “a crushing visual indictment of New York indifference” becomes art as he spots shadows and reflections in rain water, and begins to imagine portals to other worlds and the antics of superheroes. These photos help to illustrate what Keller speaks about in the neighbouring prose, bringing both emotional depth and a welcome pause.

My favourite quotes from Every Cripple a Superhero:

“The true horror of being disabled is knowing that you’re disabled and knowing that the world perceives you as such. As a monster, as a dung beetle, a deformity, a disgrace, a sorrow to your family, a waste of money, not a money maker any more, an obstacle in every respect. How do you live with that? That is what Kafka dares to ask in The Metamorphosis, bravest, cruellest of all tales. Cripple outside, superhero inside.”

-

p. 87 (italics his)

“Disability is mostly managed by the able-bodied. They are our zookeepers, we are their animals. They write books about us and the cages we live in. They write about us to advance their careers. They’re our anthropologists, writing their secondary texts about us. It doesn’t advance their careers when we write the primary ones.

Writing about us gets them grants, prizes, tenure, book contracts, speaking engagements, invitations to conferences and book festivals, seats on boards of institutions that manage the disabled and whatnot. Depriving us of writing our texts takes away all that from us. In addition, it makes sure that the blame for being disabled sits squarely with us.

Much ‘disabled’ literature still remains unpublished, even unwritten as, more often than not, conditions are too hard for many of us to get through the day and get some writing done. Yet being in a wheelchair, being sedentary, is the ultimate writing position… Well, maybe—again—the writing can be done, but what about the networking? The selling yourself part? …We simply don’t have the energy for that. There are simply too many obstacles for that.”

-

p. 99-100 (italics his)

— Yolande House, originally from Fredericton, NB, taught English in South Korea and Thailand for eight years and now lives in Toronto. Her creative writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Grain, Joyland, PRISM international, and elsewhere. She can be found at yolandehouse.com. Currently, she’s querying a memoir-in-pieces on being hard-of-hearing.

You can find Yolande House's story "Disability Tax" in Issue 301 Autumn 2024. Order the issue now:

Order Issue 301 - Autumn 2024 (Canadian Addresses)

Order Issue 301 - Autumn 2024 (International Addresses)