Posted on March 22, 2023

What is the source of joy we find in poetry? That thing that caused the prickle of A.E. Housman’s beard, that transfixed Anne of Green Gables in her desk when the teacher read Tennyson’s line, “The horns of Elfland faintly blowing.” It is what comes not from going about the woodland to see the cherry hung with snow, but evoking it in those very words, and with the delicate metaphor implied.

But no doubt I am old-fashioned in my tastes (as I think I’ve just exhibited in these examples), and when I say that I did not find much of this special joy in this book, that is not necessarily to say that it is a bad book. This is primarily a collection of confessional poetry, and it is about a difficult subject, the pain of cultural assimilation. Specifically the pain of a third wave, not the pain of the people who knew the culture and language and had them wrenched away, not the generation that suffered from their elders’ trauma through abuse and addiction, but the pain of a generation that is trying to learn what happened and to find a way back.

In a poem called “Intergenerational Trauma,” Qilavaq-Savard almost states this as her purpose:

It will take me many years to deconstruct

the heavy weight that is buried deep within my roots, before seeds

sprout, this heavy hurt scares growth with intense pains

I never personally experienced

In “Gradual Healing”:

A hero’s journey happens step by step

you will get there eventually, walk with kindness in your heart while

comprehending your circumstances, and never losing sight of

where

you are going

a hero’s journey is happening

And in “Ever Addicted”:

Ever addicted

Ways of bringing peace to never-ending chaos are learned

A withheld secret is how to unlearn assimilation from the mind and

body

Colonizers don’t want you to heal from their continual control

I’ll share a secret

The land pulls the heart together . . .

Pulling the heart together through the evocation of the land is what the best poems in this collection do. In “Blue”:

. . . this blue guides me home

this blue I delightfully drown in fills my heart to the very top

replenishing my soul effortlessly

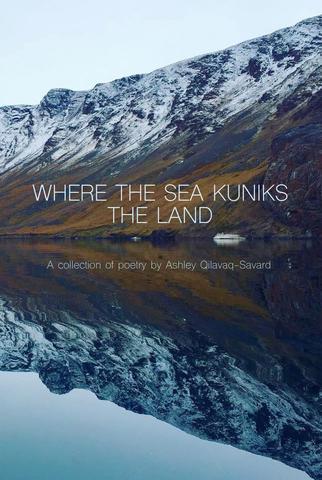

Blue is also the metaphor of the book design, which is in blue-tinted photographs of seascapes, one on the opposite page to each poem. I came to like this

more and more as I read, the book itself telling you something to reinforce the

message of the poems. This works, even though the images are Shutterstock,

and perhaps some are not even of the Arctic ocean.

more and more as I read, the book itself telling you something to reinforce the

message of the poems. This works, even though the images are Shutterstock,

and perhaps some are not even of the Arctic ocean.

Some of these poems contain very lovely images. In “Qijuktaaqpait”

(“Labrador Tea”) we find the poet sitting in among Labrador tea bushes with

their foamy white fragrant blooms:

(“Labrador Tea”) we find the poet sitting in among Labrador tea bushes with

their foamy white fragrant blooms:

I soak up this moment

every song-like sound

every sweet smell swirling about

even the feeling of my hair tickling my face in a gentle loverlike

caress

will forever bring me back to this moment when I felt like

Inuuvunga [“I am Inuk/I am alive”]

In “Skins,” while scraping the skin of a seal in the traditional manner, she reflects not just upon the inherited techniques and tools she is using, but also upon the seal itself and the manner of its death:

I can feel the elation and gratitude from the young hunter

as the act of melting snow in one’s mouth

the first of many to come

from fresh imiq [water] transferred mouth to mouth

a long-established tradition of giving the seal a last drink begins

An image the poet turns to over and over is the aurora borealis. In the erotic “Mountainous Love,” it is “our bodies moving together like the dancing aqsarniit”; in “Lateral Violence,” ”I will no longer hold space for those who cannot dance with me under the northern lights”; in “My Love and I,” “we come together like . . . the awe-inspiring aqsarniit.”

A charming memory is captured in “Tuktu,” where the six-year-old Ashley identifies the caribou herd she is seeing only with the “succulent” taste of the meat, and says it takes her a long time to see the caribou as a form of life commanding respect. Memories of her family in “My Second Mother” (“My sister was like a second mother to me”) and “My Mother Fought Colonial Oppression,” reflect the resilience of children, children in that third wave, who did not experience directly the theft of culture and language, but who suffer from it nevertheless.

As I have been writing this review, I notice how much poetry I did find in the collection, some even of the skin-prickling variety, like the breeze over the Labrador tea flowers.

However, I must also say that many of these poems are marred or even ruined by the poet’s didacticism. She cannot resist telling us what the poem means, instead of letting the story and the metaphors do the work, and the moral is very often delivered in the horrific jargon of psychology and social anthropology. “The land pulls the heart together,” but we must also understand that “letting go of bad habits to bring your head above water and in the clouds feels impossible when you are held down by oppressive systems that make it difficult to move let alone think about a future.”

The poem Crushing asks, “Why do I only matter once I overcome adversity?“ but answers in these heavy-footed lines:

life seems manageable when you cannot feel the grief of losing our

stolen

sisters, fearing erasure of identity and culture, all on top of

deep-seeded (sic)

colonial trauma

we are stuck in a system not built for us, it is no wonder we walk

around

snow-blinded into our ever-changing world that we have little

say in

yet we are expected to navigate with grace, civility, a stiff upper lip

against violated treaties and continual colonial control

The last poem of the collection turns to address (Non-Inuit) readers directly, and tells what is needed: not help, but support, respect, appreciation, admission of mistakes.

And in the spirit of that, which is good advice, and which I take seriously, I will say that Ashley Qilavaq-Savard is writing poetry that should be written, must be written, and in resorting to her didacticism, she is simply showing us under what conditions of adversity it is being written.

— Susan Haley

is still writing up her life.