Sylvie Simmons' Music Recommendation:

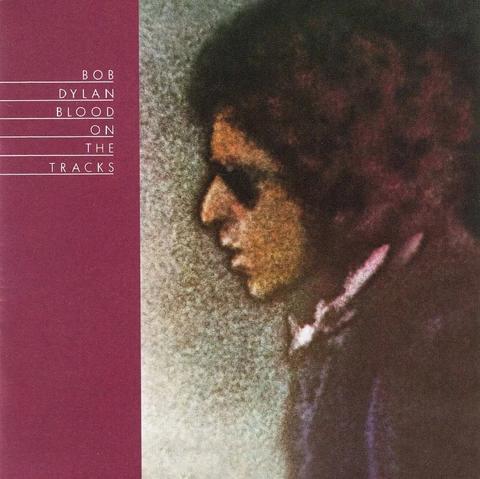

Bob Dylan, Blood on the Tracks

Something about the brainfog of a long, solitary lockdown in San Francisco, where I live, mixed with too much time spent watching TV crime shows set in London, my hometown, left me feeling unusually nostalgic. Instead of listening online to all the new albums I know I should check out, I've been wallowing in my old LPs, playing them on an old record player. Among them was one I've had for 46 years: Bob Dylan's Blood on the Tracks. It was released in 1975, before I became a rock writer and Dylan became a Nobel laureate. All that was going on in my life was young and in love and -- well you know how that goes.

A whole lot of life has happened since then. I've written books; I've even released records of my own. And Dylan just doesn't let up; his latest album Rough and Rowdy Ways is brilliant. Just stunning. But Blood on the Tracks remains my favourite Dylan album. And it still has the power to transport me back to London and a broken heart.

A while ago I started writing a series of pieces on break-up albums. This was the first of them: Blood on the Tracks and me.

It was love. Me and the boy who gave me the album, I mean. It had just come out and I was young, I didn’t have money to buy it and he didn’t either. He told me he’d won it in a card game. More likely he stole it. And stealing an LP, well, you couldn’t just slip it in your pocket like you can a CD. It was hard work stealing music back then - the kind of thing a guy would do for a girl he really loved. So Blood on the Tracks for me was a love album. I played it in my room on my portable record player over and over. Eighteen days later, when the boy broke my heart, I knew that it was a breakup album. One of the greatest.

Many years later, when I became a rock writer, Marianne Faithfull told me a story about Dylan. It was the ’60s, she said, she was in his hotel room and Bob was sitting at a typewriter. “What are you writing?” she asked Dylan. “A poem,” he said—a pause and a burning look—“about you.” Excellent seduction technique, but it didn’t work. I asked Marianne what the poem was like, and she said she had no idea. When she turned him down, he tore it up.

Blood on the Tracks is a masterpiece of torn-up love, the shreds of Dylan’s marriage. The hours I spent with that album in 1975, gouging its life out, rubbing its salt in my wound. The intensity of its emotion, the depth of its pain seemed the very essence of what I thought back then that romantic love was meant to be: theatrical and hyperbolic, a Romeo and Juliet with an alternative ending, odium instead of death.

So here we are again all these years later. I still have the original LP. It spits and jumps but nothing of it has faded. I could feel tears well up during “If You See Her, Say Hello.” There’s something about that spare, acoustic melody, its timeless North Country Fair–ness, the words that are all the more effective from being plainspoken, direct, and unfeigned. At least he sounds heartbroken. But pick a track, any track, and he might sound exhilarated.

So many colors in this painting. Where once I only saw darkness and pain, now I could see spleen—glorious, gleeful spleen—and liberation where I just saw loneliness.

“I haven’t known peace and quiet for so long I can’t remember what it’s like,” Bob sings in “Idiot Wind,” and though they might refer to the horror of being a public figure, or an abandoned husband, they can also turn a harrowing song of love and hate into a “Positively 4th Street” filtered through the clichéd line of a long-suffering spouse.

It wasn’t that long before that life in Woodstock with his wife, the kids and a paintbrush seemed so congenial.

Dylan could be as scathing as all fuck about women in his songs, but in his love songs he elevated them, idealized them, treated them with great courtliness. He and Leonard Cohen had that in common—although Dylan’s chivalry and worship didn’t come with the carnality of Cohen’s. (I do have to say that Leonard’s unmade bed seems a far livelier proposition than Bob’s big brass one.) And if both of them could turn on a woman if she should fall from grace, Cohen would find it hard to beat Dylan’s rapturous contempt and irresistible causticity.

Blood on the Tracks is all mood swings: It’s love, it’s hate, he wants her back, he doesn’t, he respects her for going, he sends his love through a third party, he crawls past her door, pities the next stranger or poor blind bum to whom she hands a dime, and then goes off and writes that rambling, “Rocky Raccoon”−like script to a TV Western, “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.”

And all of it feels true. The popular view is that it is true, that this is Bob putting his black and bleeding heart on display for the world to see. His marriage had hit the rocks (this much can be verified), and Blood on the Tracks was the revenge porn video, the divorce-court transcript in which Dylan admits to having faults (“I can change I swear”) though nothing as numerous and vile, apparently, as his wife’s, (“I bargained for salvation, she gave me a lethal dose” is one of my favorites).

But in reality, the album is so full of false leads and riddles and characters—Jesus on the cross, a rich heiress, a gang of bank robbers, Verlaine and Rimbaud—drifting from first-person to third-person (and both in “Tangled Up in Blue”) that Dylan’s supposed most personal album might really be about anyone, or lots of people, or no one at all. Which come to think of it might be the perfect way to write about disintegration, marital or otherwise.

But I wasn’t a rock writer then and none of this mattered. No, all of it mattered, and mattered so much that Blood on the Tracks became one of those records which I have, which we all have, in our armory or in our medicine cabinet or under our bed, and go to whenever we need it, whatever we might need it for.

And of course it will always be the first album that a man I slept with won for me in a card game. Maybe the only album a man I slept with won in a card game; I’m not saying.

Sylvie Simmons, a Londoner living in San Francisco, is an award-winning author, journalist and singer-songwriter. Her books include a short-story collection Too Weird for Ziggy, and several biographies, including I'm Your Man: The Life Of Leonard Cohen. Her latest album is Blue On Blue, on Compass Records. Sylvie's short stories Story with no Story, Hide and Seek and There's A Dead Man In The Park are featured in the new Spring issue of The Fiddlehead.

Add new comment