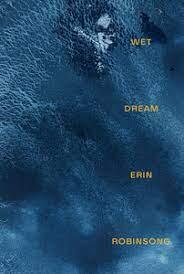

While considering my sprawl of notes from my reading, and re-reading, of Erin Robinsong’s second full-length book of poetry, Wet Dream, and wondering how to begin this review, I called to mind the following quote from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland:

“Curiouser and curiouser!” Cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English), “now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was!”

Entering the multifaceted mind-body of Wet Dream feels akin to Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole, plunging into a world of surrealistic imagery and dream logic. Like the classic tale of Alice, Robinsong’s curious book is home to immense creativity and political analysis. It is a challenging, crucial read that breaks down borders between human and more-than-human life, creating an expansive and entangled view of reality. It is poetic eco-activism at its best. The poet questions and criticizes, from the linguistic ground up, the toxic ideologies that are fuelling our current ecological crises, while inviting new ways of being and seeing that honour life in all its complex, interwoven forms. These are, admittedly, difficult poems to write about and tease out; they refuse simple summation. The moment you try to focus your attention on one element, you realize how it’s enmeshed with another, much like the nature of life itself.

As one might expect — or be sadly disappointed by — from the cheeky title, Wet Dream is a book of poems obsessed with water, not only in its imagery but also conceptually. Robinsong presents water as an ideological framework of fluidity and boundary-crossing connection that starkly opposes the rigid “evil architecture” of industrial capitalism, “an airtight nightmare” paradigm that views human life as entirely separate from and superior to other life forms. In transgressive defiance, Robinsong’s poems “work across realms” liquefying human/non-human boundaries:

That line, “What am I / Water’s bitch?” may be my favourite from the collection, and it proves to be an important one when considering a major theme in this book. . . .

Power. Who and what has it? How is it used and abused? Robinsong casts a critical eye to the industrial-capitalist powers of “colonial decrepitude, stupitude / Flowing through time as a conceptual toxin.” These overlords are obsessed with the hierarchical dualisms and taxonomic distinctions that Robinsong seeks to dispel. As the speaker in “Peonies of Dog” states:

The poet is critical of industrial capitalism’s insatiable desire for exponential growth. She defines the economy as “trashed beauty / At all costs” and reveals how this unstoppable momentum is causing mass destruction:

In the face of this suicidal resistance to change and transformation, Robinsong sends out a call to action:

Wet Dream is rampant with reminders of the various ecological crises that are currently underway, and yet, in the face of these, Robinsong’s poems can be seen as spells of the witches she is summoning, as powerful antidotes “to wet the drymouth of / Soul sickness fed on / Industrial-scale evil.”

One of the most captivating liquidities of Wet Dream is how it melds the material and the immaterial, the mind and body. Water is central to this melding: it is the essence of life that unites the brain, body, and planet. In a single poem, even over the span of a few lines, Robinsong will move through metaphors that metamorphose from the bodily into the realm of mind, thought and sky, and then onto the botanical, entangling and disorienting the senses: “A bird, a never-ending nerve / elongating thought across sky / Through verbiage into vocal foliage.” The poet presents a world where the mind is sensuous: a world of “damp thought,” “draping thought,” of “thoughtforms artforms rumpledforms / Feeling into forms’ desiring.”

The disorienting syntax is one of the great pleasures and challenges of reading this collection. In the same manner that Robinsong merges seemingly incongruous imagery, the poems formally perform this spell as lines often interrupt, contrast, and fuse with each other:

The unusual way in which the poems syntactically unfold creates a sense of individual images being dissolved in liquid movement, propulsion — or perhaps the images don’t dissolve, necessarily, but rather get carried away with the force of the poem. Like raindrops falling into a streaming river, the images lose their sense of particularity only to find a larger reality of themselves in the moving watery mass: “a wave is just ocean / Moving through as ocean as oceanic tendency to move.”

When coming back to Robinsong’s love for liquefying borders and distinctions, one can see how the poems formally and thematically embody the expansive, heightened sense of being that is achieved when realizing our intimate connection to the larger whole. Individualism is, ultimately, an illusion:

Robinsong accomplishes a lot in this ambitious collection of slippery ecologies. There are many outlying topics that I have not touched upon, such as living through a pandemic, living in a concussed brain, being in love, friendships, and psychedelic drug trips. Ultimately, Wet Dream inhabits the complexities of what it means to be alive in a body and world that is in crisis and in desperate need of new-old ways of seeing and communing that are conducive to life in its myriad forms. Water — as memory, ideological spell, and earthly elixir of all life — is key to this re-imagining. Drench yourself in these words, these waves of oddity and revelation. Heed the urgency of Robinsong’s voice as it speaks to us as if from the edge of a dream that, at first, seems too bizarre to relate to, but over time reveals itself as one of the wiser and most creative voices speaking right now into our collective (wet) dream of living.