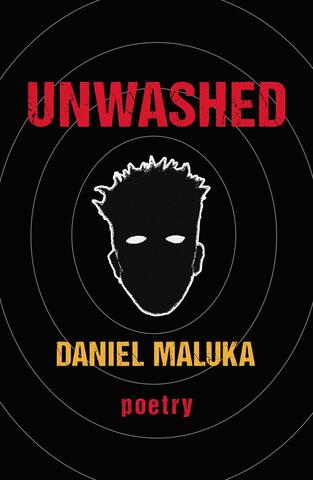

Unwashed, Daniel Maluka. Mawenzi House, 2024.

“I had things to draw.”

I first met Daniel Maluka through his drawings. Described as “Afrocentric [art that] incorporates surrealist elements to bring out what lurks in the deep recesses of the mind into the forefront of his work,” the drawings are dark, mythic, often an explosive mash-up of iconographies, in my recollection — think Picasso’s Guernica meets Cronenberg — digital illustrations in black & white, fantastical dreamlike visitations.

The cover of Maluka’s debut, Unwashed, features an etched silhouette, selfportrait of the poet’s head, backlit like a superhero branding sticker you might find on poles in Kensington Market — That’s cool, who’s this?

The opening poem, “Apartment Shadows,” sets the stage with the tale of “we,” two school kids shooting hoop, chasing ice cream trucks, marathon “call of duty zombie days.” Two kids who go different directions: one with a penchant for “misbehaving” in the shadows of the older kids; the other, attending assemblies for Black History Month and returning from his first art show:

often the place we lived

the neighborhood we shared

comes up in the news

shooting here, stabbing there

murder (2)

Often.

Let that word sink into your skin. Coat your mouth and tongue. This poem, this observant, unsparing debut, reaches your pelvic floor. Finds the pilot light. Lights it. Snuffs it out and lights it again, the pains between waiting & wanting in these lines from his poem “Form Four as Taught by George Elliot Clarke”:

“stumbling through pen, paper, and day-long BIPOC workshops. /

Waiting”

“hoping to gain a mentor’s approval with letters sent in the post. /

Waiting”

“anything to avoid mediocrity. / Waiting”

“tell me I’m good” (5)

Waiting. Wanting. Waiting. Fucking gatekeepers. Waiting sucks. Thank you Mawenzi House for picking this up. The wait is over.

When I first met Daniel, he said, “O, you know people.” Daniel, it’s you who knows people, as depicted on every single page here, how disappointingly familiar people are/can be hateful, horrifying, unbearable. Hard.

In “The Navigator” Maluka repeats the refrain “when I was a kid, I thought my dad was a spy,” shifting to “I saw my dad for who he was,” and “when I grew up I saw my dad for who he was / aware he sent his son into a world that hates him” (7).

Let that sit for a minute or two.

I say this, ask this, to let this sit, steep, because this is what the poet, the poem, this collection insists. That our reading bring us to a full stop. This isn’t TikTok. This isn’t an Instagram post. A “doomscroll.” This is a recognition. A searing moment of how this poet connects the dots, the lifelines of what he sees. An accurate reflector. We are forever changed.

While it’s true the places I’ve heard Maluka read were amongst mostly spoken word poets like Stedmond Pardy, these are not “performance monologues” and his readings don’t lend themselves to any cadences but, if anything, downplays the performative by trusting the material, the plain discomforting truth from where the speaker stands. The truth is on the page as strongly as on your tongue.

Consider: “seventy percent water / thirty percent falsehood / that’s what we are” (18). Yes, dear reader, there are a plethora of aches in a world of aches and emptiness (“I understand what you’re feeling, son, / you’re not the only one to have the empty”), empty promises, and dreams, and bodies that are warm hiding places dark, black black (your skin became my refuge”), a loving mother (“When you are miserable I can feel it too”), where the only freedom is in the

falling (“better to fall”). And a lot of sorries. Then there’s this pitch perfect poem, “black dye”:

attempting to hide ashen grey

lily white to charcoal

hoping the forces that rule time

see your point of view

small delicate strokes

one strand at a time

there is no turning

old stubborn men

life’s winters spent

reflecting summers past

trying to outrun the past

fool’s errand

The power of Maluka’s directness here and throughout this collection could be annihilating (at times is) but for the regard and care the poet has for the subject in hand, his very life. No traps. Observant, he simply calls things out for what they are (“fool’s errand”). Points to it. Speaks to it plain. Moves on.

Unwashed. Clean.

Maluka’s an artist familiar with small delicate strokes, details, the difference one strand at a time takes and makes. It is this chosen quiet care present on every page that invites, carries and holds tenderly the reader in these dark reflections shared. Like his select words, never once did I feel uncared for but felt like this is someone I can sit with in these shadows in the dark and we do. At 1:26 AM:

if we could remake ourselves

we would choose more compassion

surely

born alone and buried alone

but cannot live without each other

paradox of purpose

our shared anathema

the Aztecs knew

the whole of one’s heart

fits in one’s whole hand (28)

Surely. The poet at his most hopeful — “our shared anathema” — bringing it down to a human scale, one’s hand, one’s heart.

O, Daniel, like you in this poem, I so wish surely we would. And, you know people.

And, yes Daniel, you, your work here in Unwashed is mighty. Profoundly good. Some of the best work I’ve read this decade. Unforgettable.

— Kirby is the author of She and Poetry is Queer.