“A student of morning”

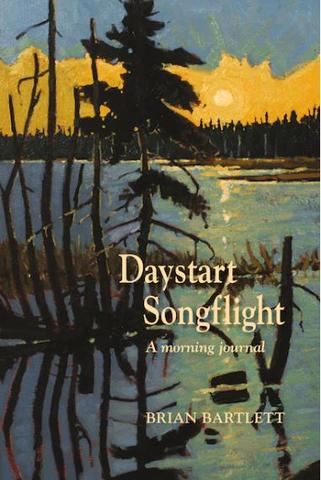

Daystart Songflight: A morning journal, Brian Bartlett. Pottersfield Press, 2021.

I began reading Brian Bartlett’s Daystart Songflight: A morning journal in March. In the dawning season, when the natural world in the Northern Hemisphere had just begun stirring to the beckoning call of the sun, its invitation to lean into the promise of longer, warmer days, and more concentrated light. I was not ready for this summons, had grown accustomed to the dark, brumal world, blurred by all-white, icy distances. My mind and body felt sluggish, inattentive. But soon after plunging into Bartlett’s exacting observation of, and hyper-curious attention to, the living, buzzing, chirping realities of the more-than-human, I was suddenly awake. Very awake.

Daystart Songflight is a plein-air journal — the second of Bartlett’s — joining the ranks of his 14 previously published books. In this journal we follow Bartlett outside over the course of 18 months, beginning in spring 2018 and ending in fall 2019, to relish in “the world-enriching particulars of small varieties […] at and after sunrise” (55). In addition to bountiful naturalist notes, he weaves in literary and historical morsels, haikus, reflections on family, aging, retirement, and travel writing. Bartlett, who lives in Halifax, visits various wild spaces in and around Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Montreal, Vancouver, Maine, northern California, and as far as Sweden, where he attends a conference on Henry David Thoreau, who is clearly one of Bartlett’s primary influences. This book was written pre-pandemic, so its sense of movement was appreciated more than ever and inspired intense wanderlust.

At the beginning of each entry, Bartlett notes his location, the date, the precise time of sunrise and “writestart” — time of writing. Early on, he questions the authenticity of writing in the afternoon or evening hours in a self-declared “morning journal”: “Morning, I’ve now decided, needs to be essential as the time of writing, and the primary but not exclusive time of subject and topics” (58). He makes clear that “the project is evolving, still finding its forms and modifying its guidelines […] as if the project were animate, with a will of its own, and sometimes that does feel like the journal’s nature” (58). I appreciated these self-referential moments, which are numerous, and the journal’s organic, wayfaring development and motion. The reading experience is akin to walking alongside Bartlett — “a student of the morning” (108), “an adventurer of slowness” (72) — with a general sense of direction, but one quickly realizes, quite happily, that our perambulating partner invites ample opportunity to detour, wander, and re-route.

Now, let me be honest: I approached this book with a slight hesitation. The term “nature writing” has earned a certain level of suspicion. At its most outdated and problematic, nature writing is synonymous with idealist escapism characterized by a distant and often romanticized appreciation of nature, as it serves primarily as a pleasant, inspiring landscape in which to self-reflect. Although Bartlett does benefit from the tranquility of the many spaces he visits and in which he reflects on all sorts of personal, human-related concerns and interests, his intense engagement with, attention to, and respect for the plants, birds, insects, and other creatures he encounters is immersive. In other words, the ecosystems that give place to his writing are not in any sense quaint backdrops for his musings. He writes about the more-than-human world with a profound reverence, curiosity, and the same intense engagement that one would expect from a biologist, but, since Bartlett is a poet, we are spared the clinical, scientific tone, and are given a voice full of warmth, humour, playfulness, and digression.

Although his ecological interests are quite diverse, Bartlett’s primary passion is clearly ornithology. Birds play a leading role in almost every one of these journals; they are the connective tissue. He is a keen observer of the numerous bird-worlds he shares space with and takes great joy in species identification, description of their songs, behaviours, and physical appearances. He exemplifies a self-proclaimed “compulsive cataloguing habit” in his lists of the first ten bird species he has heard and/or seen on various dates, noting the (in)consistencies. My inclination to groan in response to such over-scrupulousness was offset by a humorous, much-enjoyed cautionary note prior to one of such lists: “WARNING: Painstaking-birding terrain ahead” (225). The enormous extent of Bartlett’s desire to witness and share space with the winged ones is apparent in the following passage:

An appealing fiction: someone, somewhere on the planet, lives long enough and observes patiently enough to hear the wingbeats of every bird species they’ve ever encountered. Such comprehensiveness seems unachievable, out-of-reach as an ideal, yet the dream remains tantalizing, an incentive to listening and watching with acuteness surpassing our ordinary efforts and habits. (83)

He revisits this omniscient desire later on, acknowledging the immeasurable burden of such witnessing, how one might feel their “brain, imagination and sympathy put under tremendous pressure, stretched to their capacity, risked with overload,” ultimately concluding that “omniscience is not for us” (130).

A few of my favourite moments in Daystart Songflight are when Bartlett humbly contemplates the limits of human understanding in the face of morethan- human experience, opening us to the possibility of creaturely joy:

A few minutes after sunrise a Great Blue Heron flew over the ocean, not with determined air the bird often has of searching for a promising fishing-spot, but as if it were in no rush. […] I wonder if even a make-a-beeline kind of bird like a heron can find pleasure in riding air currents, in sky-dawdling. (47)

And:

At the top of an unusually tall fir, a Bald Eagle silhouetted against the sky’s blue shifted its feet and opened its beak wide, then shut it. After imagining that the eagle was watching the sunrise (do we know enough about eagles to insist they have no interest in the rising and risen sun? (170)

One more:

I recall a Purple Finch singing at the top of Mount Royal one July morning, and wonder why a primary intent of territorial assertion can’t be accompanied by pleasure in the singing, as a wolf might feel sensuous, emotive fulfillment in moonlight-enhanced howling. Too many among our species assume that we alone, or mammals alone, experience emotions, though bird psychology is a relatively young science. (117)

In a grim but necessary counter-balance to these joyful musings, Bartlett frequently refers to the varying ecological crises we are now facing. He takes note, often from news clippings, of “dangerous heatwaves” (198); “the plastification of the oceans” (23); the “stomach-lurching roller coaster that climate and weather have become during the past decade” (16); “massive bee die-off[s]” (45); “flood damage” (45) and “record-breaking floodwaters” (35); “the diminishment and displacement of waterways” (186); and “the past century’s overharvesting” (31). He is keen, however, on “resisting despair,” and the apathy that so often accompanies it. He invites the reader to consider the “countless human acts — not merely dramatic public events […] but also quiet, unpublicized acts […] of care and mercy” for the natural world, and how these “contribute, like currents to a river, waves to an ocean” (237).

In wrapping up this review, I fear there is so much I haven’t touched on — Daystart Songflight is a plenitude. As noted earlier, aside from nature writing, Bartlett delves into personal details of his life: his retirement from nearly 30 years of teaching, his loving marriage, and the death of his father, to whom the book is dedicated. He journals his reading, sharing various morning-inspired literary, religious, and mythical snippets, as well as his historical research of the numerous places he visits. No matter the topic, he proves himself a master of careful, meticulous, and, ultimately, loving attention — “not a trance but allsenses- alive alertness” (78) — which the world could use a lot more of in this age of endless distraction. As Bartlett states: “Looking, seeing, distinguishing, being reminded of and remembering — whether we’re talking about flowers, moths, piano sonatas, jazz trios, novels, haiku — make us more awake, and honour what we want and care to witness (79).” Perhaps this kind of awareness is the launching point for those “acts of care and mercy” on which the preservation of our world and its diverse species hinges. Let this book then, in its fullest sense, be a call to such potent attentiveness.

— Emily Skov-Nielsen

is the author of The Knowing Animals.

Add new comment