Simple Power: Representation and Resilience in Denison Avenue

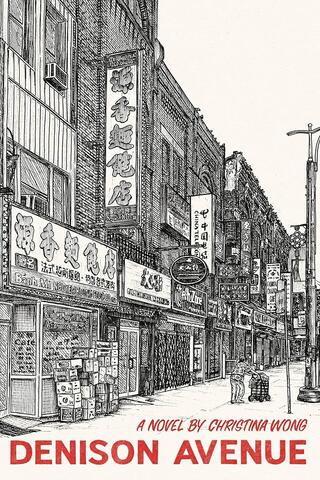

Denison Avenue, Christina Wong and Daniel Innes. ECW Press, 2023.

“Lay mang mang, ah See Heeei,” Mrs. Wong’s voice rang out. (Take your time.)

Denison Avenue, a joint work between author Christina Wong and illustrator Daniel Innes, opens with the above lines. A simple phrase of Toisan dialect, a common caring statement shared with a loved one. With this artistic choice, Denison Avenue claims space not only for the endangered Toisan dialect, but also for non-English contexts of identity. A simple but effective device — both a wedge and a mirror — emblematic of the multi-faceted power of this artistic collaboration between the author and the illustrator.

The threat of displacement runs throughout Denison Avenue. The book is composed of a novel by author Christina Wong, paired with a folio of black and white drawings by illustrator Daniel Innes. Both sides of the book follow the story of Wong Cho Sum, a poh poh who lives in the Chinatown/Kensington Market area of Toronto, as she navigates a sudden personal loss, alongside the slower, subtler erosion of the neighbourhood she has called home for her long adult life. In Cho Sum’s world, measured through the joys of her small garden’s winter melon yield and indulgences of sale-priced egg tarts from the local Chinese bakery, the astronomically-priced intrusions of gentrification are difficult to ignore, threatening not only a way of life and livelihood but, even worse, taking actual lives. Often, Cho Sum distills the yearning that attracts so many to the Chinatown/Kensington area with a mixture of empathy and resignation: “We seem to be all fighting for something to call home.”

The creep of gentrification is often so gradual that it seems almost indiscernible. This is well-captured by Daniel Innes’ gently observed line drawings, which form approximately a third of Denison Avenue’s pages. An elder in a floral-print shirt pushing a shopping cart laden with bags punctuates some of these scenes — wordlessly connecting the illustrations with the protagonist from the novel side of the project. Innes’ delicate drawings are loving renderings of the many details that make the historic area unique, from the layered neon signs hearkening back to a bygone era, to the pleasingly repeating rectangles of windows, doors and brick facades, most are notably at a two to three-storey level. In other drawings, glass-paned newer constructions dwarf the older buildings, and the humans underneath grow smaller and smaller, until they are simply silhouettes with no details. Many of the streetscapes show no people at all.

The illustrations draw their power from simply representing the neighbourhood’s changes over time. Sometimes a setting is captured in multiple temporal moments, and the reader becomes a detective, trying to locate the moment of morphing. When did that discount store close? Did the greengrocer really become a gelato place? Wasn’t there a fence where that Loblaws is? Some places simply get shuttered — boarded-up walls and windows abandoned to graffiti or stamped with a Notice of Development. Readers are left to ponder what the heavy-headed construction cranes that punctuate the drawings symbolize — finality, outrage, or hope.

The answer to this question usually comes down to a matter of perspective. Christina Wong’s novel introduces many of these perspectives, from the more privileged who benefit from change, such as newer residents in the area and eager realtors, to those trying to bridge the communication and privilege gap, such as kindly librarians, sympathetic neighbours and healthcare workers. While Innes’ illustrations take the perspective of an outside observer, Wong’s narrative is mostly told in first person from Cho Sum’s perspective. A variety of experimental forms are used, reflective of the author’s background as a playwright and artist. Soundscapes, transcribed conversation in multiple languages, trains of thought, lists, and handwritten notes on scraps of paper are layered alongside traditional prose narrative. Often, Cho Sum catalogs her surroundings:

“The daily wall calendar that we bought from Sun Wah every year hung just above the phone in the hallway. . . .The vegetable oil, the used vegetable oil, the sesame oil, and two soy sauce bottles — light, dark, stained on the outside — all on a styrofoam plate wrapped in foil sat on the counter next to the stove.”

Wong also captures the easy and caring cadence of the community’s conversations in Toisan dialect. For example, when Cho Sam’s friend Li Seem teaches her how to collect bottles for some extra income:

“‘Jow jun. Luk sik. Gwoon. Ho easy.’ (Wine bottles here. Green ones. Cans. It’s so easy.)”

Similar to Innes’ illustrations, these are important moments of recordkeeping, before the tangible disappears. Even more importantly, Cho Sum’s agency, strength and resilience is represented. In Cho Sum’s world, Toisan dialect is the de facto medium of communication, with English being the alien form. She is brave, not helpless, constantly showing up for the challenges of a system that does not take her experience into account, be it navigating the bewildering paperwork to keep her library card up to date, or trying to evade the micro-aggression of a tourist taking her photo against her will. In an especially affecting scene in the novella, Cho Sum gathers the courage to attend a community meeting to discuss the future of Bathurst Street. Cho Sum is asked, almost unfairly, what she values. She rises to the occasion: “I chose my words carefully, knowing how I spoke would betray me as it so often did.” In one of her many small successes, Cho Sum is able to represent herself and her experience, but is quickly overwhelmed by the stream of English discourse in response, which devolves into factions and self-interests. Tellingly, Cho Sum shows herself out of the room. She returns to the street.

In the deft observance of micro moments like this, Wong shows the silting up of losses in Cho Sum’s life, until she finds herself in a different existence altogether. “I looked at things more carefully, because they might not be there tomorrow,” Cho Sum reflects towards the end of the book. And yet, Cho Sum perseveres, day after day, her triumphs invisible, her losses irreversible and beyond her control.

Readers of Denison Avenue would do well to observe the warnings layered throughout the book. If basic economics and social pressures continue to erode the fragile communities of Canada’s Chinatowns, soon drawings and written records such as Denison Avenue may be all that we have left of this rich, valuable, and very human heritage. A heritage that no number of artisanal coffee shops and vegan pizzerias can replace.

— Anna Ling Kaye’s fiction has received the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers, and has been shortlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize, PEN Canada New Voices Award, and the Journey Prize.

You can find this review among others in Issue 300 Summer Fiction 2024. Order the issue now:

Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (Canadian Addresses)

Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (International Addresses)