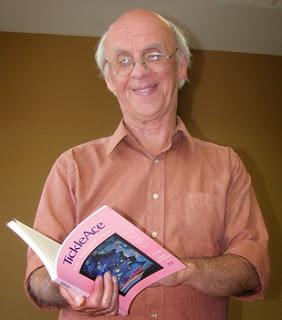

Despite the multitude of successful Newfoundland poets to choose from, Mark Callanan and James Langer’s inclusion of Tom Dawe into Breakwater’s Contemporary Newfoundland Poetry Anthology may indeed have been a no-brainer. Dawe hails from the southern region of Conception Bay, Newfoundland and is a founding member of the Breakwater Books publishing house. In 2011, he was made a Member of the Order of Canada.

Because of the recent national acclaim of some of Newfoundland’s poets, such as Patrick Warner, Sue Sinclair, and Ken Babstock, among others, the island’s poetry has been understandably drifting away from its folkloric roots. Dawe’s inclusion within this collection ensures that readers can better understand the progression of Newfoundland poetry from its original local audience to the national and international. By drawing heavily on Newfoundland’s mythology in addition to his own perspective of growing up in an outport community, Dawe illustrates the foundational strengths of Newfoundland’s poetry. In his poem “Wild Geese,” Dawe writes a confessional poem about watching two geese fly. While not explicitly stating the poem’s location, Dawe insinuates the poem’s Newfoundland location by situating the speaker on “mounds of turf / warm above wave-lit / over mossy stones.” After the setting is established, Dawe creates a link between the past and the present, juxtaposing his childhood time in this location with his current situation. He forms this link through (you guessed it) observing the flight of a pair of geese. Dawe puts tension between wanting to leave a place and yet being held to it, wanting to move on and yet wanting to stay the same. In this sense, Dawe’s poem functions as a microcosm for the grander march of Newfoundland poetry, of being pulled between history and the future.

In his poem “Wild Geese,” Dawe writes a confessional poem about watching two geese fly. While not explicitly stating the poem’s location, Dawe insinuates the poem’s Newfoundland location by situating the speaker on “mounds of turf / warm above wave-lit / over mossy stones.” After the setting is established, Dawe creates a link between the past and the present, juxtaposing his childhood time in this location with his current situation. He forms this link through (you guessed it) observing the flight of a pair of geese. Dawe puts tension between wanting to leave a place and yet being held to it, wanting to move on and yet wanting to stay the same. In this sense, Dawe’s poem functions as a microcosm for the grander march of Newfoundland poetry, of being pulled between history and the future.

The poem concludes with the lines, “They swing westward / where sky meets marsh leaves, / their shadows almost / touching me.” The geese leave; the speaker stays.

______________________________________________________

Richard Kemick is a currently an MA (Creative Writing) student at the University of New Brunswick. He recently won Grain's Short Grain Prize for Poetry.

Comments

"Folkloric" Roots

Response to James Langer

That does clarify some things. But . . .

Add new comment