Jonathan D Meyer's Reading Recommendation:

To survive the pandemic—which, let’s be honest, is very much ongoing—I dove headfirst into the abyss. Like a lot of people, I wasn’t finding joy or comfort or solace, or any of the familiar platitudes that accompanied these “strange and uncertain times,” in cooking or gardening or yoga (though I did a lot of all three). No, the cries of “we’re-all-in-this-together” that accompanied the whole affair rang hollow, because they were. Just look at the U.S. vaccination rate. Instead, I sought downer art for downer times. And I’m here to tell you, I got a real kick out of it.

It started, perhaps, with a chance encounter with the paintings of Francis Bacon during a visit to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in the halcyon days of 2019. I was returning to a city where I once lived to play music I don’t play anymore, before all travel was suspended and artistic pursuits became exclusively at-home affairs. I was also tinkering with writing a contemporary take on a Gothic horror novel, set in a city not unlike Boston, in a music scene similar to the one I used to run in. A spontaneous trip to the museum to catch up with an old friend brought me to the dark chamber of Francis Bacon, the Irish-British abstract expressionist who sought to capture “the brutality of fact.” Gory, primal, and unsettling, Bacon’s nightmare-fuel paintings offered a handy visual counterpart to kind of physiological distress I was trying to capture on the page. I have yet to get his images out of my head. I have also yet to finish that novel draft. But that’s another story.

My brief dance with Bacon in Boston helped launch a more robust dalliance with horror in general, well before the horror of the real world would come to occupy our entire lives. I checked out what was happening in horror fiction and film, trying to absorb as much as I could about the specific craft of spooky storytelling. I had long been a fan of Edgar Allan Poe and Shirley Jackson, of John Carpenter and George A. Romero, but hadn’t kept up with anything new of the ilk. Much to my horror-averse wife’s consternation, I carved out time to educate myself on how scary stories work. The pandemic and the resulting quarantine only concentrated my efforts. I could be alone with my fears. In my studies, I came to appreciate recent work by Stephen Graham Jones (The Only Good Indians) and Carmen Maria Machado (Her Body and Other Parties), as well as the films of Ari Aster (Hereditary, Midsommer) and Robert Eggers (The VVitch, The Lighthouse). Horror is indeed having a moment. But it wasn’t until I dug into the stories of Brian Evenson that my descent into oblivion was fully christened.

Brian Evenson’s biography reads like a cracked literary-world fable: A one-time Mormon church leader, whose academic career focused on the fact of violence in Western literature, writes weird, bracingly violent stories at a rapid pace, offends church elders, gets canned from Brigham Young, leaves the church, carves out a prolific career spinning tales like a Wild West Lovecraft, achieves cult status, and, finally, a rare degree of respect from the literary establishment for a “genre” writer. A classmate at my MFA—who also happened to be an ex-Mormon—had loaned me Evenson’s 1994 story collection Altmann’s Tongue, which I read feverishly between bouts of critical theory, in awe of the murderous ballads, Book of Job-retellings, and downward spirals into madness contained therein.

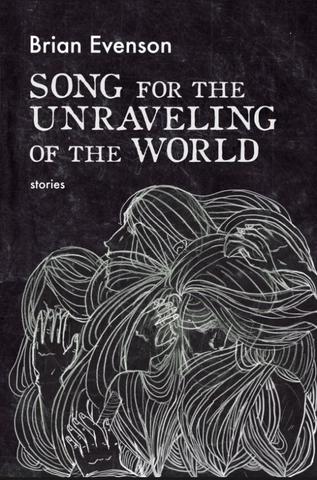

Last year, I picked up Evenson’s 2019 collection Song for the Unraveling of the World (Coffee House Press), which was making the rounds at my local indie bookstore. In the midst of my horror deep-dive during a truly horrible time to be alive, my appreciation for his work grew like a nasty tumor. I tore through the book over a couple of days during COVID Summer #1, alone on a Texas beach as I tried to work on my novel, sunburned, depressed, losing fish hooks to the Gulf, and fully under the spell of a macabre master. Song for the Unraveling of the World. Is there a title that more serendipitously captures the slow-motion apocalypse of the pandemic, of the lead-up to the 2020 election? Is there a more potent emotion to conjure through fiction than fear?

I sat on that beach, sweating under the July sun, and became fully convinced of the power of fiction again. Evenson’s work isn’t easy to describe. I could reference a lineage of weird fiction, pulp magazines, Marquis de Sade, and the grotesque and still come up short. You are better off going in cold and seeing where the stories lead you like sinister guided labyrinths. The stories are often shockingly violent, but they are not pure geek shows. In line with his academic work, which traffics in virtuality and sensation, the horrors in Evenson’s stories tend toward the uncanny and the existential. His writing style is spare and short, privileging maximum impact. Black humor creeps around the edges.

The cumulative effects are eerie and unsettling. “No Matter Which Way We Turned,” the opening story in Song for the Unraveling of the World, runs only about a page in length, and hauntingly describes an impossible being without a face. Later, the title story chronicles a father’s desperate search for his missing daughter and contains a cinematic twist ending so horrifying I wouldn’t dream of spoiling it here. Elsewhere, a filmmaker’s delusional perfectionism drives him to grisly murder, a twin (or is he?) juggles two psychotherapists, and all sorts of horrible things happen in all sorts of surprising ways, with ghastly images that wouldn’t be out of place in a Francis Bacon painting.

In case it wasn’t obvious, Evenson’s stories are not sunshiny, summery narratives that validate the resilience of the human spirit; they are desperate, downtrodden, dreadful, and dripping with paranoia. But don’t scary stories validate us in other ways? By emphasizing the outsized, absurd quality of humanity’s foibles, the slippery slope of just being alive, Evenson is essentially holding our hand through the madness. It can be exhilarating to feel shocked, the rational part of our brains suddenly at odds with what we’re witnessing. It’s akin to how humor and horror work in similar ways on similar reflexes.

In the doldrums of a long and difficult (and ongoing) year, I got a rush from letting Evenson scare me, and came to feel comforted by his sure hand as a storyteller. The nightmares didn’t cease, but they were way better crafted than reality. Reading Evenson helped me learn how to cast light on the obscene, harness the surreal, and embrace certain elemental building blocks of narrative (everything a reader needs, nothing they don’t) that I had been too quick to discredit over my time as a writer. I’ve been urging other readers and writers – short story fans and horror fans in particular – to pick up an Evenson collection, but I always add a note of warning: What you’re about to read is some pretty scary, harrowing stuff. Enjoy.

Jonathan D. Meyer is a writer from Texas. He received an MFA from the University of Houston and was the recipient of an Inprint Donald Barthelme Prize. His work has appeared in Gulf Coast, Into the Void, and elsewhere. His story Meat Off The Bone is featured in the new Summer Fiction issue of The Fiddlehead. He currently works at Rice University. Find him online: @exjonrad.

Add new comment