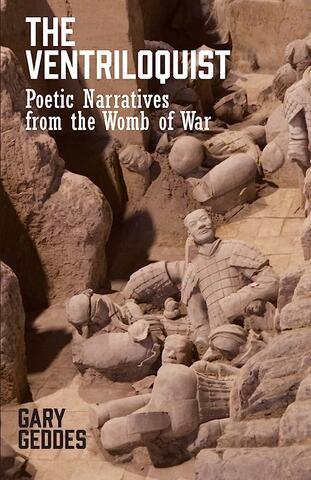

The current geo-political events in Ukraine make the release of Gary Geddes’ latest collection, (The Ventriloquist: Poetic Narratives from the Womb of War (Rock’s Mills Press), all the more timely. Geddes has gathered in this one collection four previous books on the theme of war: Letter of the Master of Horse (1973), War & Other Measures (1976), The Terracotta Army (1984), and Hong Kong Poems (1987). The collection as a whole is a powerful indictment of war, showing through narrative power and lyrical intensity the personal cost of armed conflict.

In Letter of the Master of Horse, we follow a young recruit charged with the task of overseeing “fifty of the King’s best horses” on a Spanish galleon des-tined to conquer the Americas. The ship encounters a calm, and the horses, dying of thirst, have to be jettisoned. The ensuing scene graphically reminds us that it is not just humans who suffer in war:

The men are sickened, the youth traumatized, and the poem takes on a haunted tone with echoes of Pound’s river merchant’s wife. The boy now hears the hooves of the horses in his sleep, and the culling, like the Mariner’s shoot-ing of the albatross, takes on mythical significance, signalling more death. By the time we get to the sparse closing line, “I will come soon,” the irony is clear.

War and Other Measures adopts the voice of Paul Joseph Chartier, who mortally wounded himself on May 18, 1966, in a washroom of the Canadian Parliament when a bomb he was preparing blew up in his arms. The intended target, according to records left by Chartier, was the floor of the House of Commons, killing as many MPs as possible. At the time, the act and the individual were described in the media without any consideration to the underlying psychological motives that might have driven the middle-aged French-Canadian man to such violence, both to himself and others. Geddes sees his poetry as an act of rescuing from the past. In this case, he does not so much rescue the factual life of Chartier, as he imagines and creates one that illuminates the sources of Chartier’s frustration, anger, and violence. Geddes reminds us that Chartier was a product of an inherently racist and violent society — a world which requires as much scrutiny and condemnation as the man and act itself.

In Book One, Europe 1943, we watch him kill as he watches comrades and friends killed, all in the trained, chilling, emotional detachment of military:

What makes this poem especially brave is that we are asked to empathize with a domestic terrorist. We’ve seen Geddes challenge us like this before. In an early poem of his, titled “The Tower,” he adopts the voice of the shooter Charles Whitman, who shot and killed 15 people in 1966 from the tower at The University of Texas at Austin. Geddes has often said that his first impulse and early drafts in writing are driven by outrage and hysteria, and only through subsequent drafts is he able to rein in the hysteria to craft a poem that explores the deeper personal aspects of political events. By adopting the voice of others, he is able to humanize madness and examine the deeper psychological motives behind evil. And I believe that, as readers, we are invited to exercise our own imaginations as well, arriving not at judgment and con-demnation but perhaps something resembling compassion. In War & Other Measures, it’s unclear whether Chartier is driven to psychosis by undiagnosed PTSD or les maudits anglais — another kind of war — or both, but Geddes’ empathy doesn’t run along partisan or ideological lines. His interest is in the suffering individual and our obligation to mitigate that suffering whenever and however we can.

In The Terracotta Army, the third section of The Ventriloquist, Geddes takes this technique a step further, using the polysemic voice to speak multiple voices. Now we are transported not only through psychological space but also time, to the Qin Shi Huang dynasty of 3rd-Century BCE. Geddes breathes life into 25 of the unearthed terra cotta figures by giving each a voice. There are military members such as Charioteer, Guardsman, Infantryman, and Lieutenant; tradesmen such as Blacksmith, Harness-Maker; and more esoteric titles like Spy, Lookout, Chaplain, and of particular interest to me, Regimental Drummer. The result — like Whitman’s leaves of grass — is greater than the sum of its parts. Overall, we hear in the playful musings of these colloquial monologues something of ourselves, and see that, over two millennia later, the concerns and issues that govern the politics of our daily lives are relatively unchanged.

The central figure in The Terracotta Army is the sculptor artist Bi, who we might say stands in for the poet Geddes. We never hear directly from Bi; it’s his models, the individual soldiers, who do the speaking, and we only catch glimpses of him through their eyes. The metaphor of the ventriloquist is tell-ing and apropos. While Geddes has joked that he doesn’t know if he is the ven-triloquist or the dummy, the difference is significant. Is Geddes giving these inanimate figures life, or is he the mouthpiece for their voices? In other words, is his use of the polysemic voice dramatic or Romantic? While this question cannot be answered by the poem, Geddes closes the series by reaffirming the agency of language itself, and poetry as the archive of human experience:

The relationship between artist and subject is explored further in the final section of the book, Hong Kong Poems. The book stems from the mil-itary history of Hong Kong during WWII and Canada’s involvement in it. As Geddes writes in the Afterword: “Two battalions that constituted ‘C Force,’ the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada, 1975, in all, were sent on a wrong-headed and ill-fated mission to defend the Crown Colony of Hong Kong against the possibility (read inevitability) of a Japanese attack.” The recruits were poorly trained, outnumbered, and outmatched in equipment. Despite fighting bravely, they fell in seventeen days and spent the remaining three and a half years of the war enduring “torture, slave labour, starvation and disease.” Hong Kong Poems is Geddes’ attempt to rescue their stories from oblivion and set them in poetry for posterity.

Now, however, amid their voices is also Geddes’ as researcher and writer. He travels to Hong Kong and visits battle sites and other landmarks previously visited by C Force, gathering information and inspiration. We are told that his name stems from the Old Norse gedda, “one who runs amok into battle,” and it’s clear that the speaker poet is soldier too, battling to save these stories and expose a deeper truth. In “Warning to Literary Fifth Columnists,” the poet addresses the reader directly, specifically poststructuralist readers:

Geddes places himself amid the soldiers from 80 years ago and takes aim at the critical theories that want to kill the author. For Geddes, poetry is not a jeux des mots but a weapon used to battle for historical truth. And when he is ready, he brings out the big guns of lyrical narrative:

Delisle’s bowels choose that moment to discharge, though he has eaten nothing for days. It’s a miracle of creation, or of critical acumen. The guard’s face contorts and he strikes Delisle in the mouth with his rifle butt. Then they are dragging him to the water’s edge. All work on the Reclamation has stopped. He is on his knees and has begun to sing one of those folksongs that have followed us from Sherbrooke to Newfoundland across Canada and aboard the Awatea. I can feel my legs giving out and the bamboo pole cutting into my shoulders. The fog is breaking up and sunlight reflects off the sword as it falls, repeated, on his neck. He’s remained somehow on his knees and has to be pushed over. One of them kicks his head down the small embankment into the sea.

The horrific scene etches into our imaginations, displaying the worst part of ourselves driven by hate, a reminder of the personal cost to both victor and victim in war. No party is spared. The poem and collection end with a refer-ence to the atomic blast that “ends one stage / of the ordeal, ushers in another, / rendering life, as we know it, and art / impossible.” But art is possible, as The Ventriloquist ironically shows. Somehow, out of pain and suffering, combined with imagination, Geddes’ poem emerges to speak “some precious chunk of memory / not recorded in official documents.”

There’s a powerful change of voice in the most famous war poem in English, John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields.” It’s from the poet speaker of the first stanza to the voice of the fallen soldiers of the second, from “In Flanders fields the poppies blow” to “We are the Dead. Short days ago / We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, / Loved and were loved.” Like McCrae, Geddes speaks for the dead, reclaiming their voices, their stories, and a forgotten part of their lives. And what they have to tell us isn’t pretty or patriotic. We are not told to “take up the quarrel” or grasp the torch of war, but to beware, espe-cially of language. The epigraph to Geddes’ collection is a quote by Margaret Atwood: “War happens when language fails.” If only our world leaders would exchange literature and not missiles, we might be able to avoid the destruction of life, spirit, and dignity that happens in war. Geddes’ The Ventriloquist: Poetic Narratives from the Womb of War should be first on their, and our, reading lists.