Kevin Irie's Reading Recommendation:

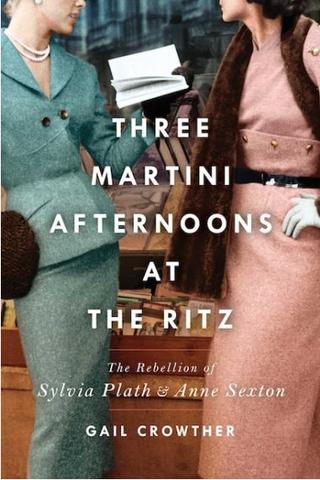

Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz: The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton

by Gail Crowther, Gallery Books 2021

If you check the table of contents in The Fiddlehead, Winter 1958, you will see the names of familiar Canadian poets—Miriam Waddington, Milton Acorn, Irving Layton, Alden Nowlan—but also the name of Anne Sexton, the celebrated American poet closely linked with the “confessional” school of writing. The poem that appeared in this issue of The Fiddlehead was Sexton’s first literary publication; two years later she would publish her debut with Houghton-Mifflin; nine years later she would win the Pulitzer Prize; sixteen years later she would commit suicide. Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz by Gail Crowther follows that trajectory and traces the path of Sexton’s career, alongside that of her famous contemporary, Sylvia Plath.

In the spring of 1959, both Sexton and Plath were attending a poetry writing workshop run by Robert Lowell at Boston University. Lowell was already a major American poet; the two young women were still starting out. Plath, an immigrant’s daughter, was married to British poet Ted Hughes, and the couple was living in Boston for a year, trying to support themselves as writers. Sexton, the youngest daughter of a well-established family, was ostensibly living the life of a Fifties American suburban housewife who had never graduated from college but had taken to writing poems.

After each session, Plath and Sexton would go to the Ritz-Carleton Hotel for martinis and chips and discuss their lives and work. Both had already suffered breakdowns and attempted suicide. Crowther chronicles these events in a compressed dual biography with individual chapters comparing how Plath and Sexton dealt with marriage, sex, mothering, writing, and mental illness. She does not delve into her subjects with the depth of Diane Wood Middlebrook’s biography of Sexton or Heather Clark’s biography of Plath, but she still captures how the two poets made their mark on American poetry, how they set their struggles against their perseverance and rebelled through their writing to reach new possibilities for their lives. Crowther unsparingly connects the background of their personal lives to their writing. She incisively examines the drugs and therapy both experienced in light of what it known now about their effectiveness—drugs no longer used, therapies now in disrepute. She details how much of what we know today about Sexton and Plath is due to the fact that their interactions and discussions with their psychiatrists are now on public record (in Sexton’s case, willingly; in Plath, less so).

Even as white middle-class women, both poets were frustrated by how gender influenced their reception in the literary world. When Robert Lowell wrote about madness and being institutionalized, John Thompson in The Kenyon Review called it “a major expansion of the territory of poetry.” Male critics were less kind when Sexton and Plath dealt with the same topics, or with menstruation, miscarriage, and abortion. Sexton asked why The New Yorker was paying her less than a male counterpart. When sharing a poetry reading in 1967, Auden asked Sexton to cut short her allotted time so he could get home to bed at his usual hour. Sexton retaliated by offering to trade places in the lineup, so she could be the final reader of the evening and Auden could leave for bed. (It didn’t happen.)

Despite seemingly so much already known, Crowther has also come up with new biographical revelations. Plath wrote two letters the night before she killed herself, one addressed to her mother. Ted Hughes threatened that Mrs. Plath would never see her grandchildren again if she insisted on seeing that letter (nor did this letter, or the other, make it into Plath’s collected letters). The critic Al Alvarez, who championed Plath’s final work as she was composing Ariel, remembers her reading poems to him from that time period which have never been published.

And as for that first Sexton publication in The Fiddlehead, it too has never appeared in her books, remaining both a literary curiosity and emblem of her determination. Like Plath, once Sexton set her mind to poetry, she practised diligently, writing draft after draft, ready to send any poem that was rejected by one magazine out to another, reaching out to improve her craft. Because she did not attend college, Sexton wrote to Lowell personally, asking to be in his class, and he accepted (how many times is that scenario played out in creative writing classes today?). There was a daring and a caring to be heard, to be seen, and both Sexton and Plath were determined to overcome the challenges, and this book memorably recounts the costs and achievements.

Kevin Irie was part of Poem in Your Pocket Day 2020. His book, Viewing Tom Thomson, A Minority Report (Frontenac House 2012), was a finalist for The Acorn-Plantos People’s Poetry Award and The Toronto Book Award. His new book is The Tantramar Re-Vision (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021). His poetry is featured in the Autumn 2021 issue of The Fiddlehead.

Add new comment