Nothing into Nothing

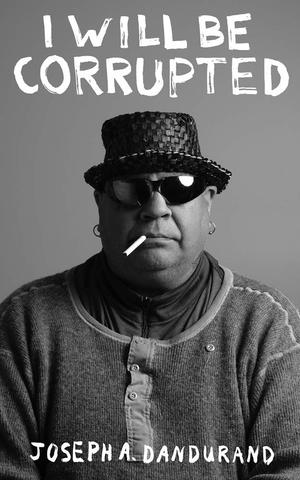

I Will Be Corrupted, Joseph A. Dandurand. Guernica Editions, 2020.

In the poem, “Whisper from you,” Joseph Dandurand rants about “one ass of an editor” (this is in the very last poem of this fine collection and presumably there for a reason), who tells him he should “add some imagery to [his] work.” I actually laughed out loud.

Joseph Dandurand is an unusual poet. He is a member of the Kwantlen First Nation and lives in a traditional community outside Vancouver. Dandurand is an English speaker and writes in English, but his preoccupations, poetic and autobiographical, are different from the preoccupations of other poets in the English canon. The imagery Dandurand deals in is perhaps just not within the recognizable space that this editor has in mind. The interplay of allusion and borrowed imagery, where a poem evokes — sometimes in just the use of a single word — a host of other poems from Shakespeare to, say, Hughes, is not the main thing here.

Dandurand’s subjects are from his own hard life, of fighting, against bullies and racially motivated abuse, and sometimes professionally, since the age of four. The ineradicable memories of abuse at residential school. The madhouse, life on the streets of Vancouver, old love affairs or hopeless new ones. And the daily struggle to put food, frequently the fish he catches himself, on the table for three children. His imagery derives from the interplay of all that with a world of spirits, of the dead, but also of fish and cranes, owls and coyotes and sasquatch.

So as far as imagery goes, the poems are full of imagery of a very unusual kind, just coming out of the fish, to start with:

. . . the smell of baked

fish filled our home as it was

the first fish caught, and the first

fish cooked slowly as the

rice pot brewed our rice

and slowly we filled ourselves

with the gift from the river

as night came and the lone moon

shone upon us and we fell

asleep on a Sunday.

That baked fish and the fish swimming the river under the moon in the blue sky of summer dusk, and the satisfaction that the poet takes in his old boat and in himself that he can still fish to feed his family, are all knit together into this poem.

This is a poet who has tea with a sasquatch (in “Desire that carved me”), receives notice that his dead friends want more smoked fish and potato chips from an owl, hears about a drowned friend from a sturgeon. In “They can howl” he finds himself playing cards with perhaps the same sasquatch, who leaves quickly after cheating, then he meets a salmon which explains to him the immortal pattern of its migration, and humorously reveals that it too had once been cheated by the sasquatch.

Many, perhaps most, of Dandurand’s poems are existential. In ‘And the Indian” he is told to sit down and cry by the spirits, and he cries all night as one of the spirits sits beside him smoking up all his cigarettes. The spirits are present all the time, they have chosen him, and even though they mischievously steal a single sock or the book he is reading (and he can hear them reading it at night), nevertheless

. . . I am protected by an old

spirit who shares a smoke with me from

time to time and we share a laugh

as the pages of my lost book

turn

What he believes (in “Created”):

We came from the sky and we fell

right here and we only move when we chase

the fish, and we live here with our children

and they will live here with their children

and so on as the river flows . . .

This is what he believes despite the hard life he has lived and the hard lives of those around him. A life of fighting beginning at the age of four and continuing on in a career of professional fighting (in “Outdone by his stories”):

I took a good beating

as some white boys did not like my

brown skin and so I waited for them

to get off the school bus and I chased them

down and swung a hockey stick at them . . .

In “For the evening,” he ponders the paradox of the survival of Christian belief among his people, even though it was forced upon them at school.

This is our time to live and to regret

And to live and to pray that our children

will not suffer as our older ones did when

they were sent away on a train to a far

away island . . .

. . . when

they were five or six and they were

homesick and the servants of God told

them that in order to get to heaven

they would have to kneel and some even

after fifty years later . . .

still kneel . . .

And then the terrible life on the streets of Vancouver (as in “I see the great cities”):

In the depths of the streets

there are creatures who

come out at night and they

seek to take the will away

from those dreads who sleep

on the ground with only

one blanket to cover

their lives.

And in “His new honours”:

I have spent some time in a

few madhouses . . .

When I began to read this book, I had some problems with the repetition of settings. Dandurand will often set up the poem with himself sitting at his desk lighting a cigarette, or else in his boat, throwing a net into the river. I counted at least eight of these fishing poems, and there are many more of the with desk-cigarette setting. Yet as I came to see, the repetition has some point. It is the storyteller getting comfortable and winding up to say something which departs entirely from the normalcy of his way of beginning, a kind of ritual just to begin right where you are.

In “What appears”:

I get a coffee and burn a smoke

and I go to my office and I sit

down and turn on some music

and I open my book and pick up

my pen and I turn nothing into

nothing as the tune on the radio

blares and the poems fall so

brilliantly and I create nothing to

nothing and this is who I am a very

lost poet and fisherman and father . . .

I think Dandurand should get the last word with that. He knows what he is up to.

— Susan Haley

finds writing her autobiography harder than fiction.

Click here to order your copy of the Spring 2022 issue!

Add new comment