A Coffin full of Books

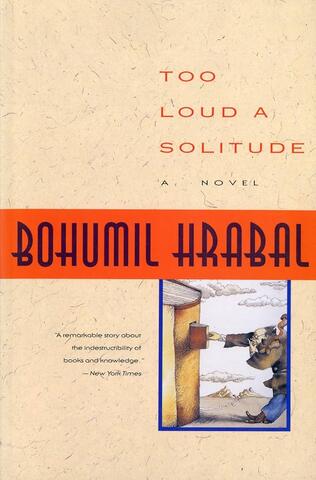

Bohumil Hrabal’s ninety-eight page novel Too Loud a Solitude opens with the following two sentences: “For thirty-five years now I’ve been in wastepaper, and it’s my love story. For thirty-five years I’ve been compacting wastepaper and books…”

A paper baler is a closet-sized machine with a hydraulic plate that compresses the material into a block that is strapped with wires, ejected onto a pallet, and trucked to a processor where the fibre is extracted to make more paper.

Too Loud a Solitude, first published in samizdat in 1976, is set during the dark decades of Czechoslovak communism. The narrator is a bibliophile named Hant’a. He works his baler in a cellar and culls works of art and literature from the endless slew of paper avalanching down through the hole in the floor above him. Along with books and magazines come heaps of bloody butcher paper, mouse nests, scraps of meat and cast-off prints of van Gogh and Gaugin. He bales it all. But he is an artist in his own small way and often positions an art print or work of philosophy atop a bale thereby elevating it and perhaps giving delight or a moment of pause to whomever might see it.

“…because today I started in on a hundred large, soaking-wet reproductions of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers, the sides of each bale glowed gold and orange on a field of blue, making the smell of compacted mice and mouse nests and decomposing paper a bit more bearable.”

Other books he takes home to his garret which is choked with his ever-growing library.

Born in 1914 in Brno, Bohumil Hrabel held many jobs, including traveling salesman, stage hand, railway employee and running a paper baler from 1954 - 1959. Talk about making lemonade from lemons. Or rather, art from pulp.

Hrabel died in 1997 in Prague, falling from a hospital window. There were various explanations, one being that he slipped while trying to feed pigeons and another that he jumped. Either way, as the grim joke goes, he was one Czech who did not bounce, a dark absurdity that fits the tone of Too Loud a Solitude and the nature of Hant’a’s seemingly endless and perhaps futile labours.

Baling paper is tough work, so Hant’a guzzles beer on the job. (A great connoisseur of the brew, Hrabel’s face adorns the label of Postrizinske beer.) “All the time I was loading armfuls of wet, red paper and my face was smeared with blood.”

While the novel has no plot, it achieves dramatic impact when Hant’a visits Bubny, just outside Prague, home to a gigantic state-of-the-art machine that makes bales twenty times bigger than his. It is not just a visit so much as a pilgrimage. The baler “rose up to the glass roof like the gigantic altar at St. Nicholas.” More than merely having a massive capacity, it is iconic of a new age, and the equally emblematic workers are buoyant young Socialists, clean-faced and healthy, who drink only milk on the job. Stranger still to grungy old Hant’a, the books being torn apart and dropped on the conveyor that takes them to the baler are all fresh off the press, having never been read, and indeed are never meant to be read much less collected, worshiped, wondered at, or argued over. It is a Socialist utopia where literature is irrelevant; for Hant’a it is Hell.

Though never mentioned in the novel, Bubny was also Hell for fifty thousand Jews who were gathered at the Bubny station in the early 1940s and sent off to the extermination camps.

Shortly after visiting this gleaming new baler in Bubny, Hant’a finds himself replaced in his grubby cellar by two of those beaming young Socialists with impeccable complexions and shampooed hair who promptly clean everything up. Adrift, Hant’a wanders and drinks. Then one night he creeps back into the cellar to pay a final visit to his beloved baler, climbs into it and flips the toggle and down comes the plate. In his own idiosyncratic way, Hant’a’s end echoes that of Hrabel himself, who apparently claimed to have received an invitation in a dream, on the very morning he died, from a dead poet who was buried in a cemetery next to the hospital from whose window he fell. What was the nature of this invitation? To lay flowers on the grave, or stop avoiding fate and take up residence in his own grave? Either way, one imagines a coffin full of books, a coffin luminous with art, including van Gogh’s Sunflowers.

— Grant Buday’s previous novel’s include In the Belly of the Sphinx and Orphans of Empire. He lives on Mayne Island, British Columbia.

You can read Grant Buday's story in Issue 300 Summer Fiction 2024. Order the issue now:

Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (Canadian Addresses)

Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (International Addresses)