From wolf to funnel spider

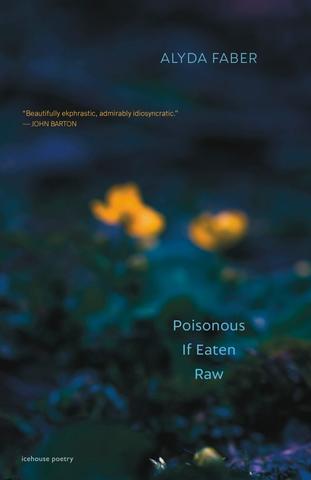

Poisonous if Eaten Raw, Alyda Faber. icehouse poetry / Goose Lane Editions, 2021

Alyda Faber’s Poisonous if Eaten Raw creates portraits of a mother twenty years after her death. Most of these portrait-poems are titled in surreal and transformative ways, imagining her mother as everything from a funnel spider to a cow being eaten to a herd of sheep. Through vivid and transcendental imagery, Faber creates detailed portraits that unveil an unfolding relationship between mother and daughter that manifests beyond physical realms and into spiritual ones.

Faber follows a semi-structured titling pattern of “Portrait of My Mother as a Vase of Sunflowers” or “Portrait of My Mother in Vincent Van Gogh’s The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital.” Some poems do break this titling pattern, and in doing so offer a different exploration of the mother-daughter relationship at the heart of this collection.

The opening poem, “Portrait of My Mother as a Funnel Spider,” begins with Faber inviting the reader to peer into “the open grave of silk sheeting / where she hides, the funnel spider unwinds” (11). The poem’s title draws a comparison to the hiding funnel spider and the mother, setting a stage for secrecy that is a continuous theme across the collection.

“Portrait: Hidden” is the first poem to break the titling pattern of “Portrait of My Mother as . . .” The very title suggests a peeling back of already surreal portraits to reveal even more hidden secrets. For the speaker to see her mother, writes Faber, she must communicate beyond the physical realm of being.

To see you, I read my own entrails

with as much certainty as that occult

art commands. I mime

what I learned from you. (21)

A child learns by mimicking a parent, but in Faber’s work, this mimicry goes beyond verbal speech. Further in “Portrait: Hidden,” the poet writes: “You were not / on one of the benches outside the fence / where parents waited for lessons to end, / but you were there, somewhere” (21). The speaker is aware of her mother’s presence beyond the realms of physical sight and sound, evoking a spiritual matrilineal link that transcends corporeal form.

So much of the way these portraits of her mother come to life is through a poetics of observation. Faber creates not just portraits of the subject of these poems but also portraits of the poet herself in what she observes. Poem after poem uncovers the details in the eye of the artist, as in “Portrait of My Mother on the Dance Floor.” Faber evokes fantastical imagery through lines such as “a ballroom balloons in her throat” (27). The perspective she writes from

Likewise, years later, her mind spirals

into blackout when the car comes to rest

on its roof, after a pirouette on ice

and silence dims the windchimes

of the shattered windshield.

All she recalls is her hand

on the door handle, as she uncoils

from the front seat and takes his hand. (27)

A particularly striking aspect of this poem is how the speaker imagines herself within her mother’s mind, and describes scenes that she would not personally have been present for. The spiritual presence outside of physical space is reciprocal, as the speaker writes with the surety and evocative detail of being present.

The first poem to break the “Portrait” titling pattern is “Unasked Questions,” and this poem offers a different perspective on the mother-daughter relationship that directly confronts the speaker’s relationship to her mother. Faber writes an aching string of words: “As if love is a daily test / that I could fail, / and I did, not only then, / but over and over” (23). How do you question what it is to be a mother? Through the tension between asked and unasked questions, Faber develops the speaker’s character as one who leans more towards observation than asking. Continuously reimagining her mother through surreal poetry suits the curious and meditative style of Faber’s poetry.

“Sheep, Again-Wolf,” explores a mother’s strength through a re-imagination of folktales and the supernatural. Faber writes of the mother, how “if she has / hope, it’s because she knows / that sheep instinctively walk / from dim interiors toward light” (49-50). The wolf reappears a few poems later in “Portrait of My Mother with Wolf,” as the poet writes how “The wolf would come back. / The same — sad, hungry. / As if she could fix the holes / that were always in him” (53). The fierce and caring portrait of motherhood extends to both prey and predator, successfully expressing a multi-dimensional room of portraits rather than attempting to paint a singular portrait over and over again.

The collection takes its title from the first lines of the poem, “Marsh Marigolds.” Faber writes how the marigolds “delight in God’s law / and meditate on it day and night, / like trees planted by streams / of water” (62). This particular poem is not described as being a portrait of the speaker’s mother, but the poem nonetheless has echoes of a parallel between mother and marigold, particularly in the lines, “Was there something / she longed to give us that spread blight / in the not-giving?” (62). The speaker expresses a longing desire to know the mother beyond her being in the position of mother.

This longing extends particularly to the portraits that imagine her mother before motherhood, specifically before the speaker herself enters her mother’s life. In “Portrait of My Mother as Abstraction,” Faber takes gallery exhibited work by modernist artist Georgia O’Keeffe and imagines her mother as a painting out of reach:

I want to touch her, but

she’s in a glass box

. . .

What shape does the mother-

daughter passion assume

after the death of the mother? (44)

Here, Faber reveals the purpose of using the mode of surrealism to craft an ongoing mother-daughter relationship long after her mother’s death. Beyond the bounds of linear time and corporeal form, such a relationship is able to be ongoing and can take any shape it likes, including that of a funnel spider, to a cow being eaten, to a herd of sheep.

There is no way for a daughter to know her mother as anyone other than a mother. But in Poisonous if Eaten Raw, Faber creates evocative portraits that attempt to bridge this gap of knowing through a process of surreal re-imagination.

— Manahil Bandukwala

is a poet and visual artist currently based in Mississauga.

Click here to order your copy of the Autumn 2021 issue!

Add new comment