By Zachary Alapi

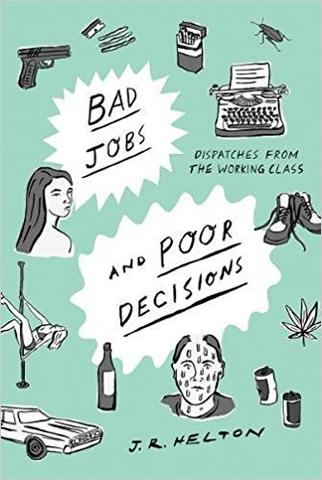

A Review of J.R. Helton’s Bad Jobs and Poor Decisions

J.R. Helton’s Bad Jobs and Poor Decisions (Liverlight 2018) accomplishes a unique feat: the weaving of social universality and cultural specificity. For Helton, that means a raw exploration of class, the most pressing and relevant issue we face, couched in the sounds and sights of 1980s Austin — the music, the drugs, the hustlers, and the grandiosity and pomp that only a state like Texas, in all its carnivalesque glory, can render both thrilling and morbid. As readers follow Jake Stewart, a burgeoning artist bent as much on self-destruction as producing great writing or visual art, as he navigates the bloated landscape of Ronald Reagan’s America. An undertone of paranoia and stasis infuses this wry and dark book with urgency and energy that even readers disconnected from the setting and era can feel.

What’s particularly intriguing about Helton’s memoir is that Jake, the book’s protagonist, consciously eschews the possibility of upward mobility by dropping out of the University of Texas after winning a writing award to pursue the craft full-time, resulting in a slew of dead-end, working class jobs. While this threatens to make one’s eyes roll, there’s something more vexing at play: the way our grotesquely capitalist society crushes dream-based decisions. Sure, Jake’s choices are nearly always impulsive and often made in self-interest, but the Romantic foundation of his desire to be an artist is noble. However, the harsh reality is that this Romanticism is antithetical to the reality of Jake’s time and place.

When it comes to “poor decisions,” Jake’s begin at an early, formative age. His eventual marriage to high school flame Susan is doomed from the start, and their mutually destructive relationship drives the first few sections of the book. This torrid romance between impulsive addicts is thrilling at first, but it’s also clearly grounded in aspirations doomed to be unfulfilled; moreover, Jake’s fascination with Susan’s father, Dean Hampton, a former NFL player turned successful novelist, introduces the first ominous harbinger for Jake: “I’d met Dean in 1978 when I was sixteen and started dating his daughter, at what turned out to be the height of his power, wealth, and fame.”

Because Dean represents to Jake that enviable combination of physical and mental prowess, celebrity, and potency, his fall from grace is alarming. As Dean morphs from Jake’s ideal future to a failed artist and irritable opioid addict, thanks to two broken back injuries from his football career, leaks start to form in Jake’s relationship with Susan. Although Jake initially stands up to an increasingly abusive Dean after marrying Susan, the idealized version of what he’d married into is already crumbling. It calls into question Jake’s motives for actually marrying Susan in the first place, given that his association with Dean seemed like an invaluable addition to his romantic relationship, one that could have made marriage seem like a worthwhile investment despite early warning signs.

With Jake’s fledgling marriage on the rocks and the realization that despite early promise he isn’t even the poor man’s Dean Hampton, reality kicks him in the ass, which leads to a slew of “bad jobs” and the accompanying anecdotes that drive the post-Susan portion of the memoir. First up is Jake’s (literally) toxic work as a painter, a job that highlights a crucial aspect of his character: his natural inclination towards isolation. This sets Jake up as a chronicler of what he sees, a tangential participant in a “working class” hellscape he’s actually created for himself. But rather than being a silent observer who harnesses his environment to create great art, Jake is a far more willing and active participant in the punishing grind of soul-crushing jobs than he’d like to admit, as seen when he first quits his job at Austin Paint and Spray after dealing with the Synott family’s decrepit grandmother:

“I opened the door to her back room. A strong fecal smell hit me in the face. There was no light. A small plastic toilet on wheels sat in the middle of the room surrounded by wads of stained toilet paper. The carpet was littered with trash, TV dinners, cans of Fibersol. As I helped the old woman to her bed I noticed quite a few beer cans piled near her headboard. [. . .] I stepped over the trash and shut the door quietly behind me. I walked out of the house and to the LTD at the street. I left my paint brushes there, my little tool bag full of putty and knives and mud blades. I didn’t even say good-bye to Jay.”

What’s especially striking after reading this kind of description is that the squalor echoes Jake and Susan’s domestic “bliss,” which serves as a reminder that the various settings’ grimy exteriors often hide something more complex and painful.

While working for Danny’s Grass and Wood as a labourer, the corrupt, “born-again” middling shyster is solidified as a character type: “‘You get a lot more business being born-again,’ Danny said. ‘I’ve been looking through the Christian yellow pages, and there’s this whole network of Christian businesses you can hook up with.’” The commodification of religion doesn’t threaten Jake on a personal level, but it does create this ominous sense that any form of authenticity has been vanquished by an almost post-apocalyptic survival instinct and that the distance Jake maintains from everyone post-Susan, including his own brother who he later works for, is a result of dealing with this frightening reality.

Even the film and television industry, where Susan ends up landing a job in production, is exposed as hollow and a dead-end for Jake, in terms of putting a final nail in the coffin of his marriage and leading to the realization that the alleged glamour of show business is yet another “bad job.” And before any hint of redemption can occur for Jake, Helton skillfully brings the book full circle through Collin, his second harbinger for Jake and a sort of anti-Dean Hampton — at least on the surface. Collin, a punch-drunk former boxer and bumbling alcoholic who works as a painter with Jake, holds up a bizarro world-mirror to Dean’s NFL credentials and substance abuse that reflects back at Jake and the pivotal fork he’s arrived at. A scene both harrowing and darkly comic ensues with Collin, filled with grotesque pathos that Helton captures with shrew description and dialogue.

It would be too easy to look at Bad Jobs and Poor Decisions as a product of white male privilege and all the baggage weighing down that narrative perspective. But it’s worth thinking about one of the platforms that heralded Helton’s book: Chapo Trap House. The “dirtbag left” comedy podcast is the world’s most successful Patreon, bringing in just under 100k per month from individual subscribers while specializing in eviscerating neo-liberals (not to mention conservatives, naturally) and their corrupt, hollow agenda. Like Chapo Trap House, Helton writes about realities most would rather ignore or dismiss in order to play identity politics on social media. Any criticism that comes from doing that is worth absorbing.

- - -

Zachary Alapi has a degree in Creative Writing from UNB. He covers boxing for The Fight City, teaches English Literature at the National Circus School of Canada, and writes scripts for various adult websites. He lives in Montreal.

Add new comment