Maybe it was the strange relationship to time the pandemic created, but at some point after this thing started I finally watched the movies of Andrey Tarkovsky. I say finally because, despite being a lifelong film lover, I’d never seen Ivan’s Childhood, Andrei Rublev, Solaris, Mirror, or Stalker. And while it probably comes as no surprise to the initiated, I can report that no other film maker has given me the visceral, profoundly spiritual sensation of film as a medium of time in the quite same way—with the possible exception of Lynch at his most transcendent.

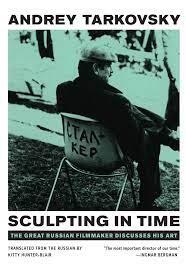

It’s for this reason that I got my hands on Tarkovsky’s still-quite-available book, Sculpting in Time (U of Texas Press, 1986, 244 pgs), that collects his various thoughts on the process of making his films. It’s a fascinating read for its biographical and psychological insights into the director alone, but the reason I will return to it again and again is because of how deeply Tarkovsky’s thoughts on art in general and film making in particular connect to my first love, poetry. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been so surprised given the fact that the author’s father, Arseney Tarkovsky, was a renown poet in Russia, but I love the many things his self-exiled son has to say about the non-rational and revelatory possibilities of art and art making:

In art, as in religion, intuition is tantamount to conviction, to faith. It is a state of mind, not a way of thinking [...]In the case of someone who is spiritually receptive, it is therefore possible to talk of an analogy between the impact made by a work of art and that of a purely religious experience. Art acts above all on the soul, shaping its spiritual structure.

Art as a way of being. Creating as a means of exploring the unknown. Isn’t this cultivation of intuition, this willingness to abandon intellectualized intent in favor of a faith in poetry’s metaphysical pull on the subconscious what we encounter in all true poems, in both the reading and writing of them? Keats thought so! And something rings so true about the idea that our souls are given some of their contours by the art that stays with us. This book also reminded me how poetry, too, “sculpts in time”—I’m still contemplating the relationship between line-lengths and breaks, meter, space, and syntax and how they might connect to Tarkovsky’s notion that there are 5 specific “time pressures” artists work with: “brook, spate, river, waterfall, ocean.”

Nathan Mader is from Saskatchewan and lives in Kyoto. His poems have recently appeared or are forthcoming in The Ex-Puritan, Grain, PRISM, The Antigonish Review, TNQ, Plenitude, and The Best Canadian Poetry. His debut book of poems, The Endless Animal, is forthcoming in 2023 from Fine Period Press.

Read Nathan Mader's poem "A Chef’s Knife from Aritsugu" in Issue 295 (Spring 2023)