Content note: mild violence, strong undercurrent of violence

They agreed that birthdays were ridiculous once you got past thirteen. Ditto Christmas. Instead, they developed a system of generalized reciprocity — a two-person Kula Ring, Amelia called it — swapping gifts only on holidays like Shrove Tuesday or St. Patrick’s Day.

Mildred’s sixteenth birthday — four months to the day after Amelia’s — they would observe by sneaking into the worst bar in the city. Which bar this was, they hadn’t decided. Until now.

“I found the worst one,” Amelia said. She poked a finger into her cup and scratched the espresso crust. “It advertises on bus shelters. It has a disco night and a ladies’ night. It has a foam night.” They sat on stools, leaning on their elbows, positioned as close as possible to the smokers, not smoking.

“Perfect,” Mildred said.

Amelia drove Mildred home. She’d taken the test the day after her sixteenth birthday. Mildred loved the Professors’ old Subaru almost as much as she loved Amelia. It always seemed ready to fall apart, which made every successful drive a small miracle. Bugs lived in the vents and there were bits and fluff in the recesses of the seats. Amelia liked to park violently, slam the door, flip her car keys. Mildred would clamber out of the passenger side yanking her tights out of her crotch, alight with pride.

Mildred’s parents met the Professors once. The meeting was Mildred’s mother’s idea. “If you’re going to spend all your time there . . .” The whole family, all three of them, were invited to Amelia’s house with its Beta VCR and banana hanger, its sink full of wine glasses. The Professors drank wine all the time, even in the bathroom. Mildred’s parents drank beer, but only at games or picnics.

By then, the friendship was three months old. Mildred tracked its progression quietly. She’d had best friends before, but in the way little kids have best friends, mostly a function of proximity. Not like this. She’d noticed Amelia back in Grade 10 when they were in language arts together, reading Greek myths. Amelia had the kind of symmetrical beauty everyone could approve of. Her hair was blonde, her nose small and dead centre. Her lips never got chapped. She was beautiful enough that people were startled and impressed by her intelligence.

One day, at the start of Grade 11, before they’d ever spoken, Mildred found herself in the girls’ room at the same time as Amelia. Without meaning to, they flushed toilets simultaneously, and without planning it, exited their stalls at the same moment. While they were washing their hands, they accidentally locked eyes in the mirror. Mildred looked away, flustered. Amelia clocked this instantly.

“The mirror will protect you, Perseus,” she said.

Mildred, awestruck, turned to stone.

After school that day they went to the coffee shop for the first time. They could not seem to tire of each other. Together, everything mattered so much less and so much more.

At the official parent meeting, Mildred’s folks sat on the Professors’ squashed futon sofa, her mother’s feet bare and cracked, her father clubbing his sternum, trying to reverse a gastric tide. The Professors sat on cushions facing the couch, offering salted soybeans from a clay bowl. Mildred and Amelia were on the floor. Finding no real common ground for conversation, the parents had resorted to describing their children, who were right there.

“When Tilley was a baby, she had no hair — not even eyebrows. I had to stick a bow to her head.”

“Amelia would give us the most sceptical looks, even as a toddler. Children just are who they are, aren’t they?”

“I’ll say. Tilley’s going through this old lady phase — she wants a monocle!”

The Professors and Mildred’s parents laughed together, really laughed, all the ice thawed, a real meeting of minds.

“A pince-nez,” Mildred corrected.

Mildred’s father smothered a belch. Amelia’s father perched on his cushion, tall and angular and almost dainty. It was impossible to see Amelia in him at all. He held his teacup not by the handle but nestled in his hand like a bird. He looked at Mildred, his face kind, and gave her the smallest of nods. “Not a bad choice, the pince-nez,” he said. “You know, regular glasses press on the temporal bone. It’s a small amount of pressure, but still. Important bit of brain under there: emotion, memory.”

On the way home, Mildred propped her elbow against the door of the minivan and covered her eyes with her fingers. Her dad was driving with one hand and picking his teeth with the other. “That tea had twigs,” he said.

“Your friend’s family seems very intellectual,” Mildred’s mother said, cranking her neck to peer at her daughter. “Do they even have a TV?”

Mildred pressed on her eyes until all was red.

— Julia Williams wrote short stories and poems 20 years ago. She parlayed those skills into a career in publishing and advertising, and is now UNO reversing back into the literary world. She is the author of the poetry collection The Sink House. She lives in Calgary with people she loves.

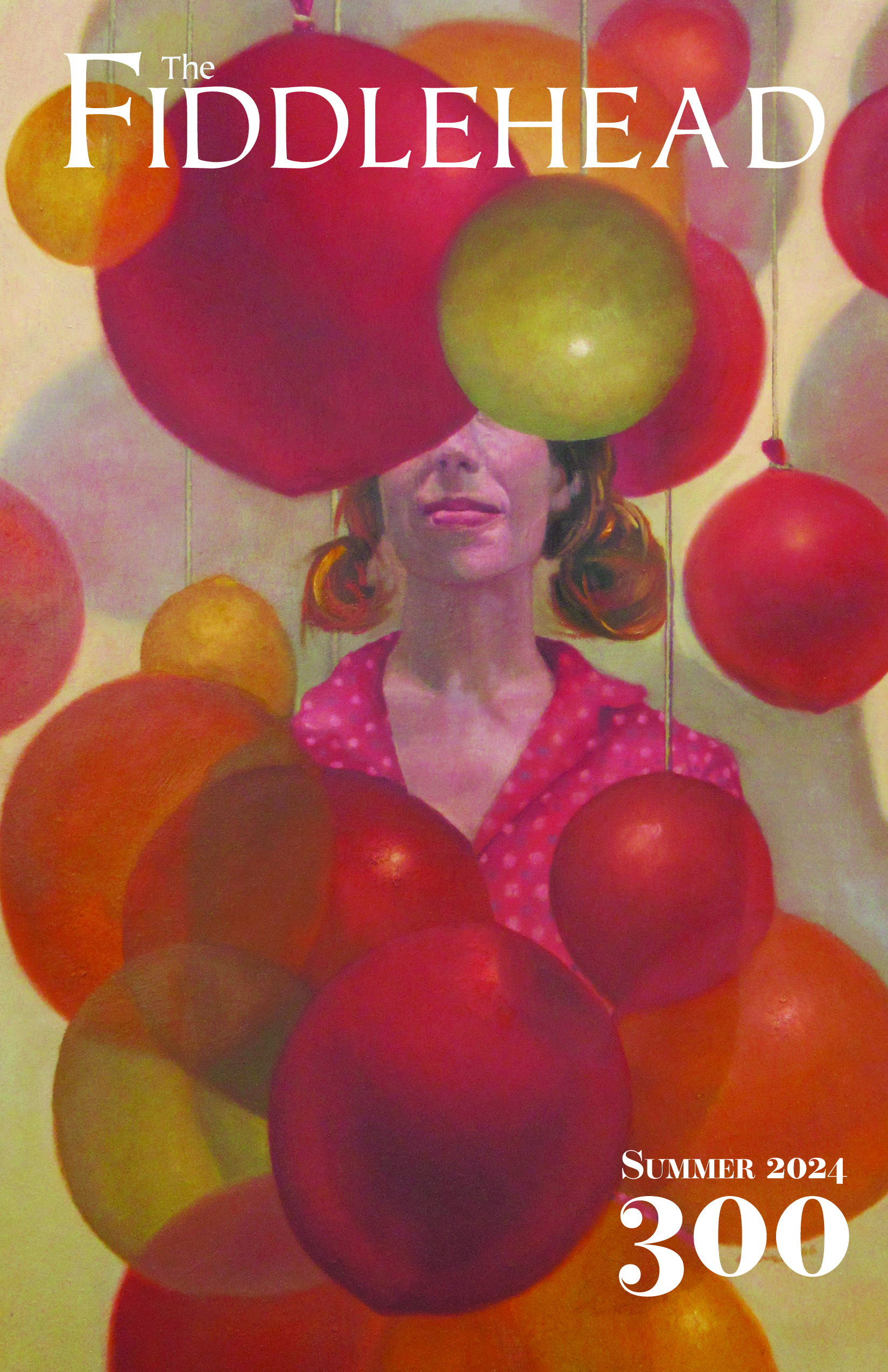

You can read the rest of this story in Issue 300 Summer Fiction 2024. Order the issue now:

Pre-Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (Canadian Addresses)

Pre-Order Issue 300 - Summer Fiction 2024 (International Addresses)