Back of the road a ways

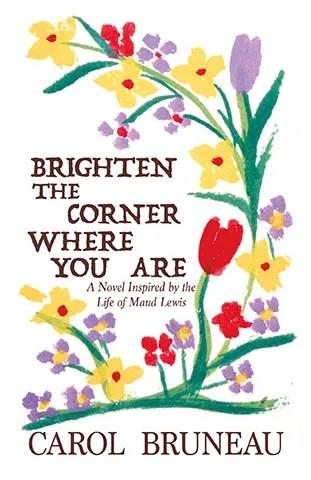

Brighten the Corner Where You Are, Carol Bruneau. Vagrant Press, 2020.

Sometimes a gifted writer can convey a character by getting an absolute sense of that character’s voice. It is a peculiar kind of ventriloquism, some kind of almost hypnotic union, and when it works it is absolutely brilliant, as it is in Brighten the Corner Where You Are, by Carol Bruneau.

It is the ghost of Maud Lewis who is the narrator of this book, or rather, not her ghost, but herself sub specie aeternitatis, and she speaks to the reader directly, expressing her attitudes from that larger perspective, and using the diction that she surely did have. That diction is one of the great pleasures of reading this book, because for Maritimers, this is the voice we have heard all our lives, in the tavern, while picking strawberries, buying firewood, paying for the hay.

It is the voice from the back of the bus recorded by Elizabeth Bishop in “The Moose”:

. . .

a gentle, auditory

slow hallucination . . .

. . .

. . . an old conversation

— not concerning us,

but recognizable, somewhere,

back in the bus:

Grandparents’ voices

uninterruptedly

talking, in Eternity:

names being mentioned,

things cleared up finally

. . .

“Yes . . .” That peculiar

affirmative. “Yes . . .”

A sharp indrawn breath,

Half groan, half acceptance . . .

It isn’t heaven Maud’s in exactly, but some kind of place — from time to time she wonders vaguely whether any of the other people will show up there, in particular her husband Ev — she wouldn’t like to meet Ev there.

Now here’s a confession. When my parents died, those Bible words after glass and darkly, “but then face to face” made me tremble with hope that I would see them again. But after being married to Ev the same words would fill me with dread like I would have to do more time with him just as things were. Even yet, gazing down at the road that winds from Digby to Yarmouth . . . what I see isn’t all bliss . . .

What we love about Maud Lewis’s art is its simple optimism, limited by materials and technique, but also enlarged by those very limitations. Seeing those oxen, those cats, that yellow bird, we might think, why is this good? But then we realize that the house paint on board — or shell — or linoleum— is telling us something deeper than these cliché images directly convey. Something about how the human spirit can express joy in the simplest of forms and with an absolute paucity of materials.

It was Maud’s amazing artistic gift that this joy breaks out through pain and disability, through rejection and abandonment, through poverty, neglect and abuse.

When I finished the painting, I set it by the window to dry, then I turned out the light and set there in the quiet polishing off Ev’s Rosebuds. With their sweetness in my mouth I took a tour in my imagination, of all the coves, hills and valleys I had guessed up for my pictures. What a nice trip. Then I imagined staying in the trailer all the rest of my days and never leaving it, not even to splash my face in the cold water from the well. One day Secretary would come to pick up that week’s work and find me asleep and try as she would to wake me, she would not be able to.

Land, I thought back then, if that were to happen, what would become of Ev?

Everett Lewis, Maud’s husband, is usually understood to have been the villain of her story, the heavy-drinking miserly man who was her husband, sometime sexual abuser of “lunatics” and possibly also female children, the man we meet in scene one of this book in the act of burying a pickle jar of coins which Maud fears also contains her wedding ring. This suspicion recurs throughout the book, while we see her temporizing about all her other problems with Ev. But her mind always turns towards the cozy, the optimistic, the sweetness of the melty Rosebuds in her mouth.

One among many others like it, the breakfast scene which occurs after the drama of Ev burying the money:

By now the range threw a nice heat, warming the velvet upholstery under my cheek. In no time the air grew toasty, a little wisp of smoke curling from where the stovepipe cut through the ceiling. Ev sat on his chair, hung his head between his knees to sober up. Kicked off his boots. As dawn broke through my window it lit squiggles of dry mud on the mat from their treads . . .

By and by he rose and dug around for the oatmeal in its paper bag . . .

The oatmeal bag had got gnawed on a bit from another kind of visitor. Oats spilled onto the floor. Ev used his hand to sweep them into my pretty dustpan and from there into the white enamel pot He poured in water from the water bucket, put everything on to boil.

This life of grinding poverty, the filth, not the tiniest bit of it escapes Maud’s attention, but it’s illuminated by her optimism: the warmth, the little curl of smoke.

I remember looking at that little house, on exhibit initially in the Halifax Shopping Centre, now in the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and thinking that it had been very seriously cleaned, sanitized even, so as to represent only that optimism, not the dirty boots, the smell of Ev’s undarned socks, the oatmeal in the dustpan that goes straight into the pot. We who knew Nova Scotia sixty or seventy years ago can remember people living in houses like this, with the cold and dirt, in a constant struggle just to stay alive. Brighten the Corner Where You Are takes us right back to that, without cleaning the floor and washing the windows.

Maud’s life story has been told before in books, and in the recent movie, Maudie (which romanticized it — a mistake Carol Bruneau does not make.) Her relatively happy and protected childhood, the affair that resulted in a child who was ‘adopted out,’ her desperate decision upon the loss of her parents to go into the poorhouse, her chance meeting with Ev and how she became his wife, Ev’s semi-abusive yet curiously caring relationship with her, the “discovery” of Maud as an artist and her growing fame, her death, the murder of Ev. All this is relayed, non-sequentially, from within the larger more neutral framework of Maud thinking about it in heaven (or wherever she is.)

Narrative dynamics suffer because of this point of view. The events of the story circle round and round in Maud’s head, along with what has become of her wedding ring, the ravens outside the window, the intentions of her first lover, Mama and the nice times they had driving around the country selling cards. Even the terrible events, the miscarriage, the murder, relayed as they are from within Maud’s temporizing mind, lack the clarity of plot culmination.

This scene, for example, poignant as it is, occurs rather close to the end of the book.

The shop girl eyeballed me . . . The pale look of the girls’s eyes helped me work up the gumption to speak

“That poorhouse in Marshalltown, can you tell me how to get there?”

Her voice was as even as if I’d asked where to find the ferry or the fish plant, she sounded so ho-hum. “. . . Just head out of town here and keep walking — you can follow the train tracks, then once you get on the road and watch for Ev Lewis’s shack, and go from there. It’s the big white place next door to him. It’s back off the road a ways, but you can’t miss it.”

What kept me reading this book, and loving to read it too, was the authenticity of Maud’s voice, and the peculiarly Maritimes flavour of her turns of phrase: the eyeballs, the gumption, the shack “back off the road a ways.”

— Susan Haley

is a novelist currently writing an autobiographical meditation

Add new comment