Battered and Bruised, but Not Down and Out

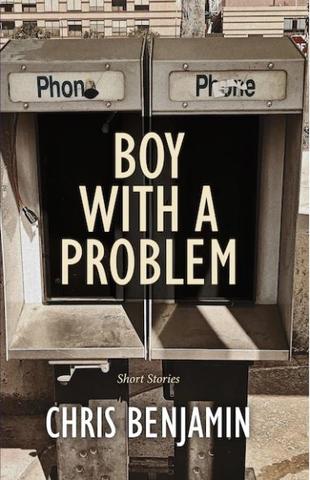

Boy With a Problem: Short Stories, Chris Benjamin. Pottersfield Press, 2020.

A range of folks whose lives unfold in the shadows of public scrutiny populates Chris Benjamin’s recent short story collection, Boy with a Problem. An orphaned teen, a date-rape victim’s dad, a dying residential school teacher, a defrocked pastor, a mentally-challenged couple in love, an impoverished immigrant who babysits to survive, and a suicidal addict and her retired-teacher drug dealer are just some of the characters whose situations the Halifax-based writer mines. A journalist, editor and managing editor of Atlantic Books Today, Benjamin once again proves to be as skilled at writing fiction as he is at nonfiction. His novel Drive-by Saviours was recognized by CBC Canada Reads, and two nonfiction books have garnered several awards.

These twelve stories represent Benjamin’s first foray into short fiction, but each features his well-honed gift for voice and a clever use of the form to take us inside his characters’ psyches. Some of his narrators stand on the fringes of others’ traumas as bystanders, while others are directly involved and engulfed. One way or another, all suffer to varying degrees the collateral damage of various injustices and exploitations.

Yes, Houston, our world is rife with problems. The ones raised here are epidemic: racism, sexualized violence, intergenerational trauma, and addiction. Two stories hint at local tragedies that have made headlines in recent years. Narrated by a father dealing with the violation of his child, “How Far Beyond Me She Has Gone” has troubling echoes of the scenario that caused Rehteah Parsons to take her life. “Home,” told by the immigrant babysitter forced into slum-living alongside neighbours who commit infanticide, suggests the case of a young couple in North End Halifax charged, and the father convicted, of murdering their newborn baby.

Regardless of inspiration, Benjamin’s slant is oblique and usually surprising. What we know about an actual situation and its surface details don’t override his inventions, intended to reveal the underlying conditions behind an inevitable outcome. The real life scenario in “Home,” for instance, appears practically as an endnote.

Taking the underdog’s view, the stories unpack the layers and consequences of traumas small and large that daily journalism can rarely touch. In an uncanny way this is fiction about creating fiction. The title and opening story, about a teenager who loses both parents in a car accident, lays out the theme supported by the rest of the collection: how the proverbial “problem” is rudimentary to fiction, but more importantly, how writing becomes an act of resistance against unfairness and of advocacy for those who struggle with all kinds of injustices. Benjamin’s wry humour and his eye for the absurd give the stories a fierce originality — even and maybe especially when the characters’ predicaments are familiar, their quirks, disasters and pyrrhic victories flying under the radar of mainstream “normal.” Infused with skepticism and compassion, the pieces convey an urgent concern for the disenfranchised. But victims and perpetrators alike share in a humanity that makes their perspectives compelling and often fraught with a darkness that would deny the prospects for much hope. Yet a sullied resilience keeps the most dejected from plunging into despair — like the addict in “Realities” who avoids crossing the bridge to her dealer’s because of the temptation to jump from it.

Benjamin’s gift is allowing these folks to speak their truths, however difficult and unsavoury these may be. As the characters reveal their various predicaments, they are unapologetically candid and without guile — rebellious, pissed off, vulnerable, scared — their language as authentic and close to the bone as can be. In fact, the language is so immersive that occasionally it threatens to speak a bit louder than the story underneath. Ultimately, though, it’s the telling of the story that takes precedence, and in this way the writer eschews and subverts the familiar convention that a short story’s every word would support the all-important ending. In Boy with a Problem the endings are often a foregone conclusion. It’s how Benjamin arrives at these that gives the pieces their resonance — and the fact that the tellers, regardless of how beaten down they are by troubles beyond their control, live to tell their tales.

— Carol Bruneau

is the Nova Scotia-based author of nine books.

Click here to order your copy of issue 288!

Add new comment