The Human Cost

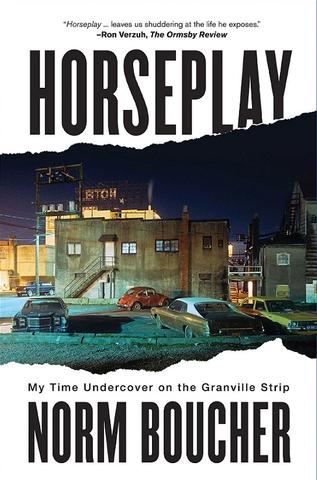

Horseplay: My Time Undercover on the Granville Strip, Norm Boucher. NeWest Press, 2020

In the early 1980s, Vancouver was plagued by a drug crisis. A port city, Vancouver was on the front line, a gateway to North America for importers of opioids from Asia. Vancouver also provided a ready market for criminals willing to exploit the seemingly insatiable appetite for heroin among the city’s addicts. In his memoir, Horseplay: My Time Undercover on the Granville Strip, decorated RCMP officer Norm Boucher provides a gritty account of the eight months he spent as an undercover operative, embedded within the city’s heroin scene on the “Granville strip,” Vancouver’s entertainment district, a section of the city centre bustling with cinemas and theatres, porn shops and strip clubs.

Writing from notes he kept at the time, Boucher presents himself as a seasoned cop with plenty of undercover experience and no illusions about the task ahead. His team has discussed and debated their strategy, and he is in it for the long haul. He will start at the bottom, work his way up within the ranks of addicts and small-time dope peddlers, and ultimately make contact with the suppliers lurking in the background. The addicts and street pushers are just low-hanging fruit. Throwing them in jail is of minimal social benefit and does little to address the root problem facing the city. Boucher’s unit wants to curtail the flow of drugs to the street, so they must build a solid case against the people who control the supply. These people — cagey, elusive, paranoid, violent — are their ultimate targets.

It all begins in January, 1983 at the Blackstone Hotel, located at 1100 Granville Street. The Blackstone is the heart of Vancouver’s heroin scene, its bar a hangout for low-level dealers, junkies, prostitutes, pimps, gays and others from marginalized groups hoping to score. This is where Boucher makes his initial contacts, his strategy a simple one: sit and observe, fit in, be patient, wait for them to come to him. For this operation he is “Nick” from Prince George, a low-profile dealer with ambitions to expand his operation to Vancouver. Boucher is more than ready for this assignment. He is familiar with the behaviours of addiction. He has studied the strip’s unique subculture. He has tailored his appearance to suit his surroundings. When the time comes, he will mimic the symptoms of withdrawal. He has scarred himself, “poking needles into the veins of my arms” to recreate the telltale markings of a long-term heroin user. But still, now that he’s here, sitting among the people he has to persuade, befriend, and do business with, he is “nervous as hell.”

It will take time before I get anywhere close to them, so I take a sip of cold beer, and try to decide who is dirty. Rick Crowley is sitting alone and, like the other hypes, no longer pays attention to me. I can’t really tell if he or the others are dealing, but it really doesn’t matter because I’m not going to score heroin tonight. I’m here for the long run, and I only want to be seen, get a feel for the place, and give them an idea of who I am before I become a threat to them. It also feels good just to see their faces.

As a cop employing subterfuge to infiltrate enemy territory, Boucher’s training allows him to remain emotionally detached. Over the eight months of his assignment, he witnesses misery, brutality and cruelty in abundance and does not intervene — though at times he is tempted. Instead, he keeps his team’s ultimate goal in sight. Unavoidably, however, he does become friendly with some of the Blackstone regulars, learning their stories, glimpsing their humanity. It is one thing to launch a scheme to send ruthless criminals to prison. It is quite another to do the same to people who have suffered personal calamity and find themselves dependent on hard drugs to get through their days and nights. This, it seems, is where the emotional core of the book resides: Boucher’s empathy for the likes of Jodie and Deedee, who struggle against their habit but are no match for the daily high that eases their way through a hostile world while gutting their health and making criminals rich.

Boucher ends his memoir with a plea for better understanding of addiction as a disease. He makes the point that while the burden on police and medical professionals is still a heavy one, society has come a long way since the 1980s, when drunk driving was the subject of jokes and drug addicts were considered criminals and often jailed. But while attitudes and treatment strategies have progressed, the dealers and suppliers are still out there, still profiting off the misery of others. Many years and thousands of innocent victims later, we find ourselves in the midst of another crisis, battling a drug of choice that is more destructive than any that have preceded it.

Horseplay is not just a gripping account of one cop who puts himself in harm’s way. Norm Boucher’s memoir also tells a poignant tale of people whose struggles against an insidious enemy most often end in defeat. Sadly, it is a story that many of us have seen played out on a personal level. For that reason alone it bears repeating.

— Ian Colford’s

new book of short fiction will be published by Porcupine’s Quill in 2023.

Add new comment