Judy LeBlanc’s Reading Recommendation:

Outside the car windows rubble from a volcanic eruption three hundred years ago spreads on either side of the Highway across the sprawling Nass Valley. It's a lonely place, lava strewn and calcified, yet it’s not a place without growth; struggling vegetation and lichen covered rock. Mid-September, and the temperature has dropped since we left BC’s south coast where oversized RVs continue to clog the highway in late summer. This highway is empty. Road signs are in the Nisga’a language only. The weather is uncertain which way it will turn. I feel I'm in a foreign place, somewhere I don't quite belong. I’ve just finished Jordan Abel’s fourth and most recent book, Nishga, and as we cross the beautiful devastation of the Nass Valley, I’m reminded of the tone of this book, its heartbreaking sense of loss and dislocation, its longing for connection.

Unlike Jordan Abel I’m not of Nisga’a heritage though, like him, I’ve been estranged from my Indigenous ancestry, in my case Coast Salish on my mother’s side. Abel’s ‘settler’ mother took him and left his father, Nisga’a artist Laurence Wilson, when Jordan was an infant. They moved from Vancouver to Ontario where he was raised barely aware of his father or his Nisga’a roots.

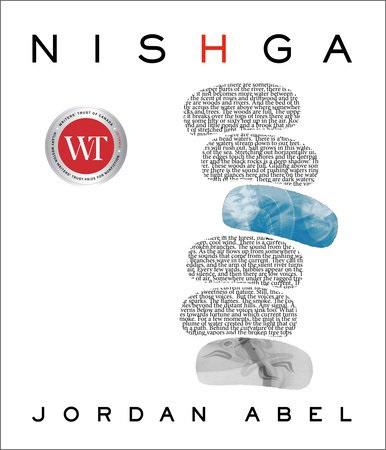

Since my mother died six years ago, I’ve been researching and writing about my own severed Indigenous heritage, so it’s not surprising Abel’s exploration of cultural estrangement resonates so strongly for me. However, it’s not only the book’s subject matter, a familiar one these days, but Abel’s skill in realizing his far-reaching artistic vision while imbuing the work with poignancy, intelligence and honesty that makes it so moving. You feel he gives it his all: his mind, his heart, his virtuosity. In Abel's own words the book consists of “found archival documentation, creative non-fiction, photography, concrete poetry and academic inquiry." As with his identity, it’s not a genre that’s easily categorized.

Both Abel’s paternal grandparents went to residential school leaving in the wake of their experience what he calls a “shadow” which perpetuated intergenerational trauma. Abel mostly doesn’t address this head on other than through academic discussions relayed through transcripts of presentations and dialogues in which he’s spoken on the subject. Nevertheless, the shadow presence of trauma thrums in the background of the book and is brought forward conceptually in one section through a series of increasingly blurry photographic images of Google sites dispensing advice on suicide that gradually clarify into a photograph of a plaque on a brick wall that reads COQUALEETZA INSTITUTE, the name of the residential school Abel’s grandparents attended. Underneath is the inscription This stone was laid by Duncan Campbell Scott. Landing on the name of one of Canada’s most outspoken proponents of residential schools is a gut punch, and likely more effective than pages of personal testimony about the familial dysfunction that ensued as a result of his grandparent’s residential school experience.

For me reading Nisga’a has opened the possibilities of incorporating photography, concrete poetry and found text in my own work; however, it’s in the sections titled Notes where the finest, most personal and most poignant writing happens. There is something organic in the way these thoughts emerge out of all the material with which Abel is working and therefore we as readers are also working. Each Notes section begins I remember… with an urgency in the refrain as if this remembering must be a matter of necessity. Here, the voice is vulnerable as he wrestles most personally with the ambiguity of his identity. He questions why no one pointed out the incongruity with his family history when as a child he convinced his mother to send him to a Christian elementary school. He briefly describes meeting his father for the first time at age twenty-three and afterwards was “disappointed that the hole in [his] life was still there.”

In the Nass Valley, the all-glass front of the Nisga’a Museum looms skyward in the tiny remote village of Lax̱g̱altsʼap. The young woman who takes us on a tour is clearly proud of its repatriated cultural objects. In the gift shop, Jordan Abel's book Nishga is on display. "I just finished reading that book," I say, and the woman at the desk asks me about it, says she hasn't read it yet. She doesn't seem to know Jordan, and though I'm certain she’ll read the book and may very well come to know him, in this moment the disconnection of which he writes is palpable. The loss is evident on both sides, on his and on theirs, and yet there is hopefulness in the fact that the book is there, in the woman's eagerness to read it, in that place where we're surrounded by those cherished cultural objects, repatriated.

Our car is a miniature, and it’s as if we, too, have shrunk as we drive in silence back across the awesome ruins of the valley where now the late afternoon sunlight flirting through the metallic clouds paints an otherworldly sheen on the landscape. We pull over and bundle up, get out to touch the rocks, to be surprised by their near weightlessness in the palm of our hand. The cold wind drives us back into the warmth of our vehicle, and we continue on our way.

I’ve come to believe in signs, and it occurs to me that it’s an interesting coincidence that so soon after reading Nishga, I find myself in Nisga’a territory. What does it mean to grow up so far from the land of your grandparents? Unlike Abel, I’ve had the privilege of living where my Coast Salish ancestors lived for thousands of years though I’ve known the territory primarily through a colonial lens which means for much of my life I’ve not known the land. Tuning into the land is more than appreciating its beauty. It’s inextricably mixed with one’s culture, as is language.

Beyond the irony, there’s something profoundly heartbreaking in the way that Abel appropriates generic descriptions of wilderness from Cooper’s Last of the Mohican’s and superimposes it in tiny, barely readable text on images of his father’s art, thus putting his work “in dialogue with [his] dad’s work.” For Abel, his relationship to Nisga’a land has been one of imagination, and in his words has been “deeply fraught.”

The lava beds are a result of a volcano that erupted in the Nass Valley three hundred years ago, around the time Europeans arrived in this land. It wiped out three Indigenous villages and killed thousands of people. The bed is 38 km long and 12 metres deep.

"Why have I never heard of this earthquake," asks my husband.

"I had a BC public school education, and I never heard of it," I say.

Abel describes more than one encounter in which he’s put in a position where he must justify or explain his Indigeneity. Here, his writing is reminiscent of Claudia Rankine’s poetic explorations of racism.

"How much white blood do you have in you," Abel is asked.

"My blood is red," he says, and though you applaud his response, you feel his weariness.

Finally he says, "I wrote this book because I thought I could write my way home...It turns out that wasn't the case...I didn't find my way anywhere but deeper."

At the end of the book, I’m left with the same prevailing sense of absence that I feel when leaving the Nass Valley, and yet not without thoughts of regeneration, of repatriation.

Judy LeBlanc’s collection of short stories, The Promise of Water was published in 2017. Her work has appeared in numerous Canadian literary journals, most recently, Prairie Fire, and she’s currently completing a collection of personal essays.She lives on the unceded traditional territory of the K’ómoks First Nation. Judy's creative nonfiction essay "Beneath the Din" is featured in the Spring 2022 issue of The Fiddlehead.

Comments

You make me proud my

Add new comment