Two new short story collections by Canadian women writers explore female characters and their relationships to home — home as a place, an idea, or an emotion. Both authors find the grotesque and surreal in familiar, domestic, or mundane surroundings.

Meghan Bell has published poetry, fiction, and essays in literary journals and other venues. She is an editor at Room Magazine and is perhaps best known to date for her compelling essays on wealth disparity in Canada, a subject on which she is uniquely qualified to expound. In “Erase and Rewind,” the title story of Bell’s debut collection (which has recently been snapped up by Clique Pictures for adaptation to a short film), mathematician Luisa re-experiences in reverse her twelve-day relationship with classmate Nick. Fleeing his apartment when their date ends in coerced sex, she steps in dog detritus and makes a startling discovery as she backs away in revulsion:

Luisa thought about all of this, when she realized she was walking backwards. She felt her foot step into the imprint she’d left in the shit, toe-heel, and then lift, dry, and step back onto clean concrete. She looked down and her feet stopped moving. She was standing directly behind the shit, which was now — miraculously — intact.

As she relives the past she re-examines her miscommunications with Nick and ponders ethical dilemmas raised by her new ability not just to reverse but to erase the past. Reverse chronology can be a tricky, invasive device — Martin Amis (Time’s Arrow), Harold Pinter (Betrayal), Atom Egoyan (The Sweet Hereafter), and Colleen Murphy (The December Man), have all used it to superb effect — and Bell proves herself equal to the task, balancing the flow of events and internal reflections. Beginning at an ugly climax (in both the narrative and anatomical sense) we know from the outset that the relationship is doomed, but this heightens rather than diminishes the tension and poignancy when we read the more lighthearted, hopeful beginning of their relationship. Bell’s restrained and witty interpolations of voiceover style commentary explore Luisa’s thoughts without weighing down the pace. The image of a pie chart disappearing slice by slice becomes a metaphor for writing a story, reconstructing, and reordering experience through imperfect murky memories.

In “Most Likely to Break,” teenager Natalia works for a company that clears out houses destined for foreclosure. Cleaning the kitchen, she finds the frozen body of a tabby cat in the refrigerator. Her co-worker Noah comes to help her, but in their confusion dealing with the corpse begins awkwardly to pressure her sexually. Another co-worker intervenes, driven partly by his own attraction agenda, and a three-way confrontation ensues that is both slapstick absurd and uncomfortably serious.

Bell writes with dispassionate clarity about fraught social issues (consent, rape culture, sexism) in a way that feels natural to character, without overt agenda. The predators in her stories are washed out by the bright light cast by the courage of her protagonists. In “Thunderstruck,” Rossi, a talented 17-year-old hockey player juggles the intense pressure of competition and her secret affair with Luke, her 40-year-old coach.

Puck drops. I send it back to Evie, who passes to Vanessa, who takes off toward the offensive zone. I scream for the pass, but she sends it across the ice to Marion instead. Intercepted by their centre. She catches me flat-footed and zips past the blue line into our zone.

Earlier that morning, I sat on the toilet seat of a Starbucks bathroom with three positive pregnancy tests between the fingers of one hand, like Wolverine’s claws. I trailed them across the stall wall as I shook the fourth test dry. The little crosses are the same colour as the blue line.

“Rossi! Skate!”

I realise I’m staring at the blue line.

Not all stories in the collection are equally compelling — some are quiet, without enough at stake, and characters blend into one another. Bell is strongest when she embraces riskier forms, the grotesque or surreal. “I Was Made to Love You” is an unpredictably sweet and charming story in screenplay form about ageless, androgenous, naked plasticine people who do not speak but communicate with convincing clarity. The witty short piece “Pieces” anatomizes a breakup in a series of postcard stories in second person riffing on body parts and organs. At their best, her young, precocious, athletic, jaded girl-women disarm us with their refusal to dwell on their lost innocence.

The day before my first day of high school, my older sister, Sara, gave me some advice I still follow today.

“Be nice to weird people, you never know who is going to end up being a school shooter.”

Householders is the second collection by Toronto-based Kate Cayley, who is also a prolific poet and playwright. Home is the central theme of these nine stories — home as place, memory, or aspiration. The obverse of this is travel: in nearly every story, characters arrive at new strange houses or return to old familiar-but-distanced ones. In each case the visitors feel displaced, the visits feel like trespasses.

Four connected stories follow the lives of Naomi, who flees a cult in rural Maine to set up a new life in Toronto with her young daughter, Trout, and Sarah, who remains in the cult with her daughter, Strawberry. In the third story in the series, “Travellers” Trout and Strawberry, now middle-aged women, meet at Strawberry’s home/art studio in Berlin. Cayley skillfully creates a complex, nuanced portrait of a close friendship with its shared memories and disconnections in a way that avoids soap operatic indulgence. Their reunion is fraught with unresolved memories, feelings of guilt, and resentment. Strawberry has painted a Bosch-inspired work, teeming and grotesque, depicting their childhood in the commune, which triggers Trout’s belated realization of her own mother’s trauma. “Strawberry had finally stopped talking, looking at Trout. Trout, who was weeping, found it difficult to interpret her mother’s face in this last picture, since both her hands were clamped over her mouth.”

In the conclusion to the cult quartet, “Piss and Straw,” Trout has resolved not to watch her mother die a protracted death, demented, in a nursing home, so she takes Naomi to Maine (where Trout was born) to the home of Sarah, Charlie and their friend, Saul, the final survivors of the cult. Trout realizes uncomfortably that she is completing the cycle that began when her mother displaced her as a child; she was too young to consent when Naomi fled with her, now Naomi is too old to consent to the return. Trout’s guilt is balanced by the relief she feels in leaving her mother in a place, however imperfect, that feels like a home.

This idea of taking her mother back had come to her before the lockdown or the notice about the border’s impending closure, but it was the extremity of those things that made her act. Everything Trout thought of as normal had been suspended, including the things she had regarded as fundamental decencies. Why shouldn’t she also do something dramatic and unimaginable, like take her mother back to the place she’d been most herself and leave her there.

A motif of faith runs through Householders. In “Pilgrims,” the central character, whose real name we never learn, has created a blogger alter ego, Sister Bernadette, an American Catholic nun, who is intrigued by the Camino, the pilgrimage route between northern Portugal and Spain. In reality, her partner, Nickel, has recently left her in a sinking trailer in the woods with his adult son, Stevie, who is quadriplegic from a recent car accident. In truth, she has no religious faith. Her blog catches the attention of Leonard, a retired teacher searching for spiritual companionship. As their online relationship develops, “Bernadette” finds herself in a complex moral dilemma that engages questions of identity, spirituality, and deceit. Is a lie still harmful if it does only good? The backdrop of the pilgrimage offers another dimension to the idea of home or holding house. A pilgrimage is defined by its liminality — the journey, not the destination.

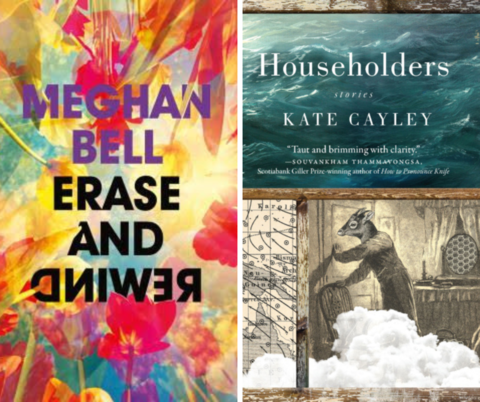

Cayley’s sentences are often long but expertly crafted, with a quiet power. She mines a broad range of forms — fairy tale, song, music, visual art, and literature ranging from Shakespeare to TS Eliot. Her style is realistic, but the effect of her stories can be disorienting, dreamlike, with a sense of something just beyond reach. In the book’s cover image, a well-dressed antelope-man appears to be barring himself into a room with an oval honeycomb mirror, as vapour (or smoke?) rises from the floor. The effect manages to be familiar and domestic, alarming and grotesque — an unsettling beauty perfectly suited to the stories within.

— Clarissa Hurley

is a freelance writer and editor, and former fiction editor for The Fiddlehead.