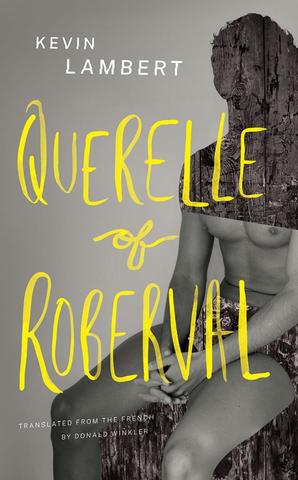

Querelle of Roberval

Kevin Lambert, trans. Donald Winkler. Biblioasis, 2022.

When Kevin Lambert’s Querelle of Roberval rolls into a sleepy Québécois sawmill town, teenage boys and young men line up at his door. And the rumours start to fly. Is he a madman, a murderer, or worse? He is “Roberval’s bogeyman . . . he spirits away adolescents, corrupts them, carves them up, devours them . . . he lives in a cave . . . and works side by side with your godchild’s girlfriend.” What is suspected of Querelle is indeed true of the corporate greed feeding the land and its workers into the pine slabs and pulp of its global markets. Lambert’s fiction syndicale (union fiction) packs its devastating, lyrical punch along the struggling picket lines of mill workers whose men and women understand the social, economic, and operational exploitations that keep the factories barely open — and profitable. When their boss sends hot coffee spiked with bleach to his freezing workers — and then attempts to run them down with his truck — all bets are off. These folks have been stabbed in the back by forces far greater than themselves. If the book has a metaphorical form it is, top to bottom (all puns intended), impalement. Those who seek to be impaled by Querelle give themselves willingly to be recognized; to belong; to make their way. Early in the book, it’s explained that before returning his boys to their mothers, “Querelle impales them once again”. Similarly, and side-stepping the need for spoiler alerts, let’s just say that the book unabashedly thrusts and skewers its way to its end — like its literary antecedent, Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest. The struggle to make a life for oneself amidst the smouldering violence that unrelenting inequality metes out day by day is, next to the thrilling and brutalizing sexualities on display from Querelle, often the most riveting sections of the book. These people fuck, guzzle, tell bad jokes, and take turns stabbing their bosses and drowning misbegotten children with the delight, and horror, of unapologetic payback. The motto of this story is: fuck with labour, fuck yourself.

Taking structural cues from Greek drama, the book bends into the minds of its characters pushed to the limits. Craft-wise, these moves allow Lambert to fuse the workers’ day-to-day struggles into their fantastical and phantasmagoric sensualities. In the Prologue, the door is opened to “…all the boys who come into Querelle’s room, who line up to be taken from behind, he strings them on a necklace, the beautiful young-boys necklace he wears around his neck as our priests do. . . .” His hunger is the town’s own seething desire oppressed by the crush of corporate greed— sometimes masculine and sometimes feminine and sometimes both at once. His male co-workers privately stop to study him; the women see something of themselves in his swagger. The socially-awkward “Indian” Bernard, sees new hires, like Querelle, as a threat to his job. . . . The long-time workers like himself . . . seem lazy beside them.” Yet Querelle rivets him. At the Mise en Jeu, a local bar where the strikers carry on haphazard strategy sessions, a local boy buries his head under Querelle’s arm. Bernard spots “his curvy, girlish behind. Even if he shaved himself close, Bernard’s cheeks would never be so smooth. . . .” He’s got some experience. “He himself had a taste of it with the guys in his dormitory when he was working a logging site in the North.” Bernard isn’t the only one. The fathers of the town have it off with each other on fishing trips jealous that Querelle takes from their sons what they themselves cannot. Likewise, Jézabel, a sometime barmaid and a hound dog in her own right, has dumped her girlfriend for being clingy but hates spending the night alone. She knows that the workers’ situation is worse for women: “caught between the owner’s claws, the perversions of the market in general and the stock market, the idiocy of the new environmental norms, the capitalist system, which has no regard for a man’s dignity.” She likely recognizes something of herself in Querelle: “a great void within . . . abandoned at the edge of a bottomless drop where people wanted to see him lose his footing.”

Ne’er do well “poignant boys, fifteen, sixteen-year-old bums, three scamps too young to have dropped out of school, three terrorists in the making” are the story’s three Shakespearean witches, roiling in mutual exchanges of filth and spunk on a basement mattress. They “go at it two by two, the second takes turns busying himself with his boys’ cocks.” Like Genet, Lambert finds beauty in these outcasts. “Sometimes, in the half-light of a Canadian Tire lamp that’s lost its shade, the three suck each other off, alert to their positionings, as flawless as the beautiful compositions of Old Masters.” Opening the window to the over-heated room “they have to sleep spoon fashion to keep warm.” The thrill of the read is, to some degree a brutal sexual prowess that a de Sade or Pasolini might admire, but it is also the readerly experience of being delivered into excruciating and hilarious interiorities.

Translated from the French by Donald Winkler, Lambert’s skill allows him to slip easily from one point of view to another. For instance, on Christmas Eve with nothing to do, he makes love to “a little Querelle” for whom Querelle holds “respect and curiosity, as if he were confronted by his own fetus….His boy is impressive, he accepts his prick with innate ease, it finds its ways in as if born to it./The good boy loves the jolts of Querelle’s solid shaft, to which his own responds with reciprocal shudderings in his hand. He didn’t know there existed torsos as perfect as that of the man penetrating him.” Or, “Jézabel thinks he looks like a model. She tells him so, he laughs. Thanks, Sharapova. I might have the look, but not the pay. Their conversation soon turns to the strike. . . .” Here, the writer slides from Jézabel’s point of view to Querelle’s to their shared narrative. While the book delights in the swaths Querelle cuts in the asses and hearts of the town’s young hunks, it seethes at the razing of labour’s hopes and dreams. Lambert’s Querelle of Roberval is far more than a titillating romp sniffing around the blades, bar stools, and crotches of beleaguered labour; it is a blistering hunt for a liberation that may never come.

—thom vernon

is a writer, actor, and academic.

Click here to order your copy of issue 293!

Add new comment