The poems in this collection are peppered with questions: “who handles pecking order, ever?”; “I must never lose / you, but are we allowed a break?”; and my favourite one posed to her mother on the phone, Is your house tidy enough / to write in? The questions propel the poems and help shape a loose narrative of doubt, loss, insight, and over time, a wry acceptance of history and herself.

The first poem, “Epiphany,” describes her beloved black dog capturing rocks on the beach. She recalls the dog always looking for something and wonders the implications if the dog had stopped looking.

Metaphors were easy then, not only the sky,

but migrating everywhere. And now everyone is arrow

arrow, arrows. Everyone harpoons.

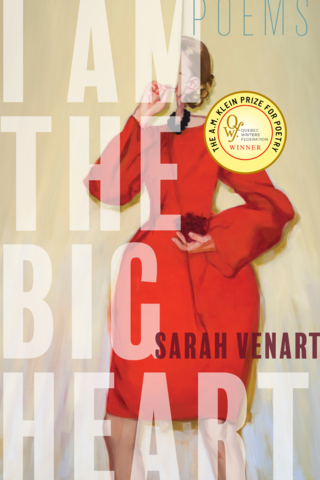

And I am the big heart, aren’t I?

Change was more accessible to her back then on the beach with the dog and the rocks and the tides under a big sky. But these days she feels pinned down by people, their demands, their requests, and even by those who inhabit her past, especially her mother. When her dog was being put down, in the dog’s “last/ second I whispered, Squirrel.” I loved this intuitive moment, the whispered word that helped the dog become an arrow, making that spring into death easier with the familiarity of chasing something. The speaker was part of the arrow-movement and concludes she has a big heart . . . or does she? Self-doubt pops up often.

Of the sixty-eight poems in the book, twenty-one are written in couplets, but they never feel easy as the go-to form, more like an inching towards some kind of clarity in couplet baby-steps. In “Origami,” she says,

At night I close my eyes and let my thoughts

become my feelings, let my feelings point their corners

into dark corners. I fold the word daughter

over and over until it contains the word duty.

Often she elaborates on the changes young children pull into our lives. Later in the poem she says “. . . watching a thing/ become another thing makes me hopeful:” Transformation is possible in the string games she sees demonstrated on Youtube and in the squares of paper folded into birds or turtles or whatever. In little pieces of time, these changes look easy, even effortless.

What the speaker desires for herself is transformation that endures, but she’s afraid of it too. In the poem, “What Are You Waiting For?,” she lights a fire at the edge of a field, bakes her foil-wrapped potato and green beans, roasts marshmallows on an aspen branch, and then dumps water on the flames before heading home. But her fire devours the entire field. Venart is deft with selective details of the household, the farm, the waiting room, the sports centre and here she catalogues the plants that take over the charred field, “the wild doilies of carrot” and a riot of clover, vetch, irises, wild grasses, and lupins.

The field says it forgets

who struck what mineral against another mineral,

says it forgets all but that spark laid bare

on the flat palm of its clearing.

And it’s hungry to be marked again

by that kind of danger.

Fire is cleansing, and the speaker wants to be burnt over and cleared for new growth, innocent as fireweed. She is wounded by the world she often details so beautifully, but as the poems unroll we hear more of her past, how love has failed her, and in particular, we hear of her complicated relationship with her mother.

In “The Rising Action” Venart reveals something of her mother’s past:

I knew her name

changed three times. I knew the date and place of birth,

and much more. But in the black dust of her moods,

she took me back to that foundling house.

I saw why the bread knife was sometimes

at the ready. I know enough:

Her mother could start fires, butcher meat and roast it, make quilts, milk cows, and make oatcakes. She ran a farm and took care of the physical needs of her children. But sometimes this mother looked through her daughter, “and said words no one could love.” In section three we witness her mother’s decline and death and what it reveals about her. Pain reminds her mother “to be fearful when necessary.” She accepts her family changing her pyjamas and diaper, administering medications, taking care of her at home.

In “The Art of Waiting,” adult daughters “wait outside the bodega/ for our mothers to return.” And the dead mothers do show up, some in housecoats, another in uniform, another “firewoman-like,” even one who resembles a nun. Sometimes the mothers come in groups or solo through the door. Sometimes they’ve forgotten honoured treats, those gifts they bring with them after an absence.

The wait becomes endless. Each time more mothers come

swiftly through the tinkling door, our throats leap.

See our grim foundling smiles, see the flowers we picked

from the cracks in the sidewalks? We’re so ready to hand over

these bright bits of gratitude for our mothers in return.

Sure enough, her mother strides grimly through the door, “a little unfamiliar in slippers and kimono.” No smile, no hug, no greeting, but “without delay she corrects my sweater buttons.” Even though the daughter recalls the reprimands, she is happy to see her mother. She’s flexing that conscious, perceptive love of an evolving human being who has been hurt by someone else’s limited version of love but accepts and even loves the person anyway.

By the time we join Venart for “Supper Hour,” she’s found a bit of what she’s longing for. She’s chopping broccoli at the kitchen island while her young daughters tear around the room.

I like to think

I have it down pat: metal handle, grim chop

through the rough stalks, my real self obscured

by this mother self, lip lines, hips pressed

firmly forward into the task.

She moves on to turnips and beets, enjoys the weight of the knife, the sound of the steel. We see something of her mother in her, the dextrous wielder of the knife, the satisfaction of a job well done. Maybe part of motherhood is learning how to mother ourselves, accepting what our histories have given us to work with, learning how to spin it into something new.

In “Darling Citizen,” she sums up her understanding of what a big heart might be.

The heart knows what to do, what not to do again.

In earth years, my heart is ridiculously young.

It blinks closed, it glistens open to herd the blood.

It’s the red eye waiting for the lunge.

It parts my reeds and silt and lifts me out.

The big heart is a big eye, blinking, glistening, watching, and waiting. A red eye, maybe from crying, maybe from a long journey, maybe from the sheen of the world. If we allow it, the heart can be a solid editor, sieving self-doubt and grief, making room for a speaker, renewed but not too naive, nurturing a sparrow-like wry hope. Venart doesn’t have a lot of answers to her many questions, but we know she’ll never give up asking.

The poems in this collection have been considered and beautifully polished over time. In the rhyme, assonance, and pacing of the sonnet “Valentine” I heard echoes of George Herbert. The cleverly crafted palindrome “Against Confession” suggests how memory both protects and fails us. She picks up material from her children’s comments, her mother’s journals, and what she overhears at the sports centre. Venart is open to whatever the world has to say to her, a patient receiver, a big-hearted writer.

— Lynn Davies’

latest collection of poetry, written for children, is So Imagine Me.